There are certain standards that need to be met with regard to the terms “indigenous sovereignty” and “state sovereignty” and it begins with definitions. The former applies to indigenous peoples, while the latter applies to independent States. Current usage in Hawaiian discourse tends to conflate the two terms as if they are synonymous. This is a grave mistake that only adds to the already confusing discourse of sovereignty talk amongst Hawai‘i’s population. Instead of beginning with the definition of the terms and their difference, there is a tendency to argue native Hawaiians are an indigenous people as if it is a forgone conclusion.

Indigenous studies make a clear distinction between the terms. Corntassel and Primeau’s article “Indigenous ‘Sovereignty’ and International Law: Revised Strategies for Pursuing ‘Self-Determination,” Human Rights Quarterly 17.2 (1995) 343-365), refers to indigenous people as a “stateless group in the international system.” Defining a stateless group, Corntassel and Primeau cite Milton J. Esman’s article, “Ethnic Pluralism and International Relations,” Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism 27 (1990): 88, where he defines non-state nations as ethnic groups that do not have a patron State of their own.

While the State has its origins that date back to 1648—Treaty of Westphalia, it wasn’t until 1982 that the United Nations officially recognized indigenous groups when it formed the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations. That year the Working Group came up with its definition of indigenous populations. “Indigenous populations are composed of the existing descendants of the peoples who inhabited the present territory of a country wholly or partially at the time when persons of a different culture or ethnic origin arrived there from other parts of the world, overcame them, and, by conquest, settlement or other means reduced them to a non-dominant or colonial condition; who today live more in conformity with the particular social, economic and cultural customs and traditions that with the institutions of the country of which they now form part, under a State structure which incorporates mainly the national, social and cultural characteristics of other segments of the population which are predominant.”

According to Corntassel and Primeau the Working Group’s definition was so broad that “any non-state nation … could fit under the term ‘indigenous population (p. 347),’” which would go outside the Working Group’s focus on tribal populations. They argue that under such a broad definition any people that are non-States such as Basques, Kurds, Abkazians, Bretons, Chechens, Tibetans, Timorese, Puerto Ricans, Northern Irish, Welsh, Tamils, Madan Arabs, or Palestinians could identify themselves as “indigenous people (p. 348).”

Seven years later, in a move to limit the definition to tribes, the term “tribal peoples” was inserted in Article 1 of the 1989 Convention concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries, No. 169, adopted by the International Labor Organization. Article 1, provides: “(a) tribal peoples in independent countries [States] whose social, cultural and economic conditions distinguish them from other sections of the national community, and whose status is regulated wholly or partially by their own customs or traditions or by special laws or regulations; (b) peoples in independent countries [States] who are regarded as indigenous on account of their descent from the populations which inhabited the country, or a geographical region to which the country belongs, at the time of conquest or colonisation or the establishment of present state boundaries and who, irrespective of their legal status, retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural and political institutions.”

An “independent country” is an independent State that is a self-governing entity possessing absolute and independent legal and political authority over its territory to the exclusion of other States. All members of the United Nations are independent States. The ILO was clearly distinguishing between indigenous tribal peoples and the States they reside in. The 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples also makes that distinction in Articles 5, 8(2), 11(2), 12(2), 13(2), 14(2) (3), 15(2), 16(2), 17(2), 19, 21(2), 22(2), 24(2), 26(3), 27, 29, 30(1) (2), 32(2) (3), 33(1), 36(2), 37(1), 38, 39, 40, 42, and 46(1).

The ILO Convention covered the “what” are indigenous populations, being “tribal peoples in independent countries [States],” but it did not satisfactorily determine the “who.” This was somewhat addressed by Jose R. Martinez Cobo, Special Rapporteur of the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, in his 1986 Report on the Study on the Problem of Discrimination against Indigenous Populations, which stated:

“Indigenous communities, peoples and nations are those which, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing on those territories, or parts of them. They form at present non-dominant sectors of society and are determined to preserve, develop and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identity, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal system (paragraph 379).”

“This historical continuity may consist of the continuation, for an extended period reaching into the present of one or more of the following factors: (a) Occupation of ancestral lands, or at least of part of them; (b) Common ancestry with the original occupants of these lands; (c) Culture in general, or in specific manifestations (such as religion, living under a tribal system, membership of an indigenous community, dress, means of livelihood, lifestyle, etc.); (e) Language (whether used as the only language, as mother-tongue, as the habitual means of communication at home or in the family, or as the main, preferred, habitual, general or normal language); (f) Residence on certain parts of the country, or in certain regions of the world; (g) Other relevant factors (paragraph 380).”

“On an individual basis, an indigenous person is one who belongs to these indigenous populations through self-identification as indigenous (group consciousness) and is recognized and accepted by these populations as one of its members (acceptance by the group) (paragraph 381).”

Throughout his report, Cobo also distinguishes between indigenous populations and the States they reside. On this note, Cobo recommends:

“States should seek to gear their policies to the wish of indigenous populations to be considered different, as well as to the ethnic identity explicitly defined by such populations. In the view of the Special Rapporteur, this should be done within a context of socio-cultural and political pluralism which affords such populations the necessary degree of autonomy, self-determination and self-management commensurate with the concepts of ethnic development (paragraph 400).”

“Countries with indigenous populations should review periodically their administrative measures for the formulation and implementation of indigenous population policy, taking particular account of the changing needs of such communities, their points of view and the administrative approaches which have met with success in countries where similar situations obtain (paragraph 404).”

In the 1996 Report of the Working Group (paragraph 31), representatives of the indigenous populations stated, “We, the Indigenous Peoples present at the Indigenous Peoples Preparatory Meeting on Saturday, 27 July 1996, at the World Council of Churches, have reached a consensus on the issue of defining Indigenous Peoples and have unanimously endorsed Sub-Commission resolution 1995/32. We categorically reject any attempts that Governments define Indigenous Peoples. We further endorse the Martinez Cobo report (E/CN.4/Sub.2/1986/Add.4) in regard to the concept of “indigenous.” The 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples does not provide for a different definition of indigenous peoples, but rather declares their rights within the States they reside.

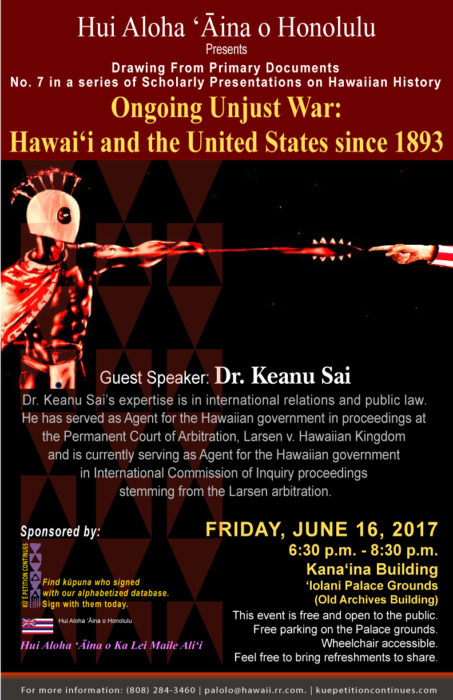

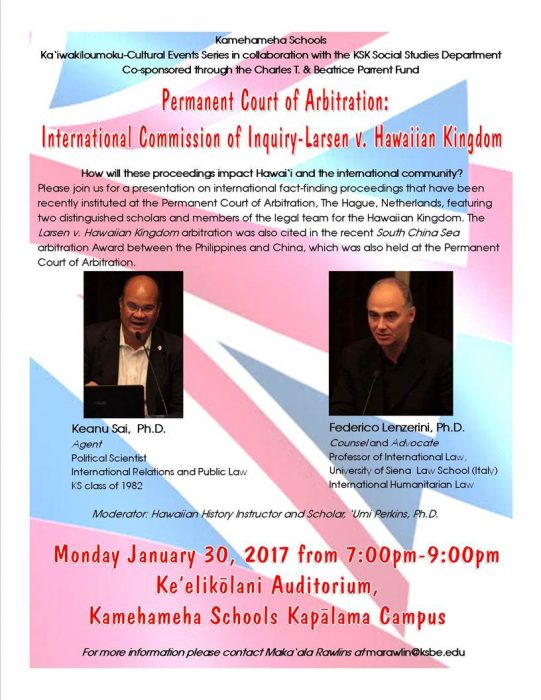

In 2001, the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, concluded, that “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.” There are no indigenous people in the Hawaiian Islands because the aboriginal Hawaiians formed the State themselves, comparable to other Polynesians who formed their own States such as Samoa in 1962, and Tonga in 1970. Both States are members of the United Nations. The only difference, however, was that Hawai‘i was the first of the Polynesians to be recognized as an independent State. Furthermore, Samoans and Tongans do not refer to themselves as an “indigenous people,” but rather the citizenry of two independent States.

This is why it is paradoxical to say that natives of Hawai‘i (kanaka) are an indigenous people because it would imply they do not have a State of their own. This labeling of Hawaiian natives as indigenous people is an American narrative that has no basis in historical facts or law other than people just saying it. Rather, natives are the majority of Hawaiian subjects, being the citizenry of the Hawaiian Kingdom that has been in an unjust war by the United States since 1893.

The

The