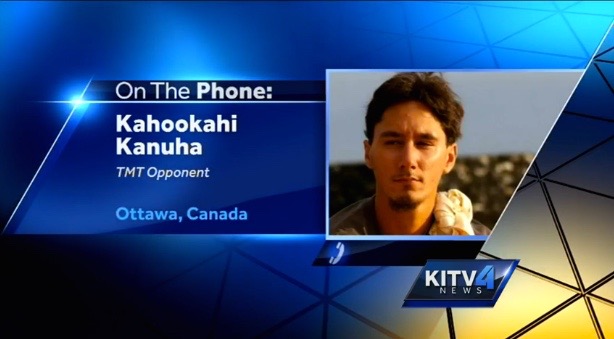

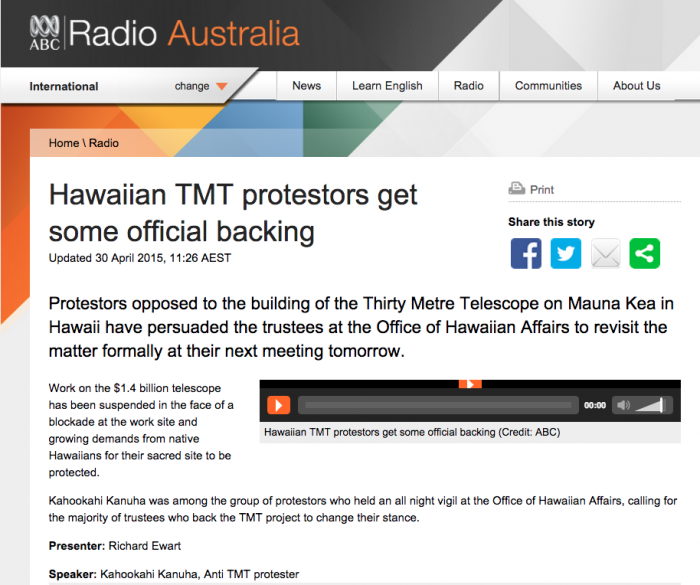

On April 17, 2015 the following cease and desist letter was sent by Dexter Kaiama, legal counsel for Chase Kaho‘okahi Kanuha and Lanakila Mangauil, to Douglas Ing from the law firm Watanabe and Ing who is the legal counsel for TMT International Observatory, LLC. Kanuha and Mangauil are the leaders of the protectors of Mauna Kea.

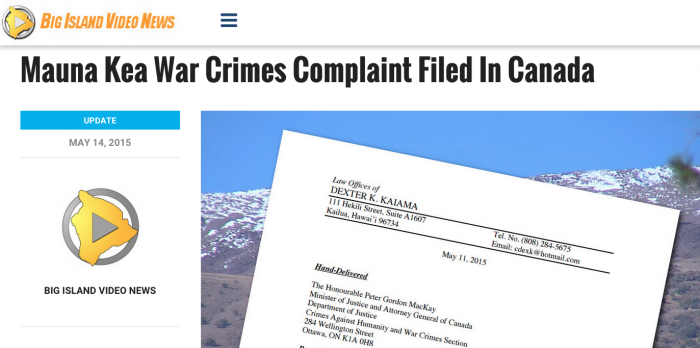

The cease and desist letter was also sent to the Canadian Department of Justice, who investigates war crimes, the Prosecutor the International Criminal Court, the Board of Regent of the University of Hawai‘i, the State of Hawai‘i Board of Land and Natural Resources, the Trustees of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, County of Hawai‘i Police Department.

******

TMT International Observatory, LLC,

by its attorney James Douglas Ing

First Hawaiian Center

999 Bishop Street, 23rd Floor

Honolulu, HI 96813

Re: WAR CRIMES CEASE & DESIST NOTIFICATION- Construction of 30-Meter Telescope on Mauna Kea

Dear Mr. Ing:

This law office represents Chase Kaho‘okahi Kanuha and Lanakila Mangauil, both being Hawaiian subjects of the Hawaiian Kingdom with vested undivided rights in the lands as native tenants under Hawaiian law.

Your client, TMT International Observatory, LLC, is hereby directed to immediately cease and desist in the construction of a 30-meter telescope on the summit of Mauna Kea that is situated within the ahupua‘a of Ka‘ohe, district of Hamakua, Island of Hawai‘i, Hawaiian Kingdom. The ahupua‘a of Ka‘ohe is public land under the administration of the Minister of the Interior of the Hawaiian Kingdom under An Act Relating to the Lands of His Majesty the King and of the Government (1848). The Hawaiian Kingdom has been under an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States of America since August 12, 1898 during the Spanish-American War.

Under international law, extensive destruction and appropriation of property not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly is a war crime. The construction of permanent fixtures on public property that belongs to the Hawaiian Kingdom government is extensive destruction of that property.

On behalf of my clients, be advised that the construction of the 30-meter telescope is a war crime in violation of:

- Article 56, Hague Convention, IV (1907), “All seizure of, destruction or willful damage done to institutions [dedicated to religion, charity and education, the arts and sciences, even when State property], historic monuments, works of art and science, is forbidden, and should be made the subject of legal proceedings;”

- Article 53, Geneva Convention, IV (1949), “Any destruction by the Occupying Power of real or personal property belonging individually or collectively to private persons, or to the State, or other public authorities, or to social or co-operative organizations, is prohibited, except where such destruction is rendered absolutely necessary by military operations;” and

- Article 147, Geneva Convention, IV (1949), “Grave breaches… shall be those involving any of the following acts, if committed against persons or property protected by the present Convention: …extensive destruction and appropriation of property, not justified by military necessity and carried out unlawfully and wantonly.”

The United States military’s omission of preventing the destruction of the public property of the Hawaiian Kingdom is also a war crime in violation of:

- Article 55, Hague Convention, IV (1907), “The occupying State shall be regarded only as administrator and usufructuary of public buildings, real estate, forests, and agricultural estates belonging to the [occupied] State, and situated in the occupied country. It must safeguard the capital of these properties, and administer them in accordance with the rules of usufruct.”

The Final Declaration adopted by the International Conference for the Protection of War Victims in 1993 urged all States to make every effort to, “Reaffirm and ensure respect for the rules of international humanitarian law applicable during armed conflicts protecting…the natural environment…against wanton destruction causing serious environmental damage.” In its advisory opinion in the Nuclear Weapons case in 1996, the International Court of Justice stated, “States must take environmental considerations into account when assessing what is necessary and proportionate… Respect for the environment is one of the elements that go to assessing whether an action is in conformity with the principle of necessity.”

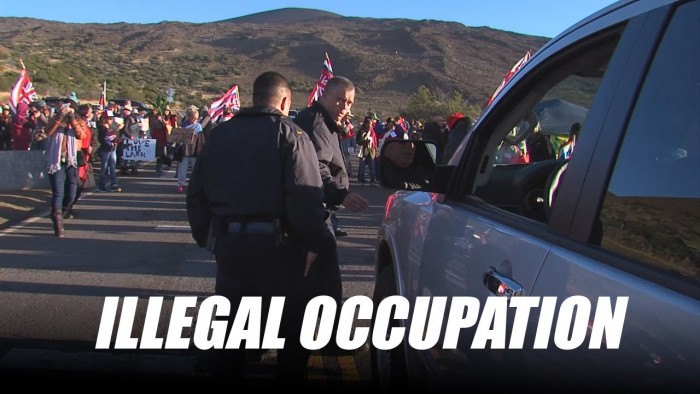

War crimes of destruction of real property on the summit of Mauna Kea belonging to the occupied State have been committed since the State of Hawai‘i leased 13,321.054 acres of the summit of Mauna Kea to the University of Hawai‘i in 1968. Thirteen telescopes have been constructed as permanent fixtures since 1970, and your client will make it fourteen. TMT International Observatory, LLC, has already committed the war crime of destruction of property when it began the construction of the 30-meter telescope by breaking ground, and has committed secondary war crimes of unlawful confinement (Article 147, Geneva Convention, IV) when 31 individuals who were preventing TMT International Observatory, LLC, from committing additional destruction.

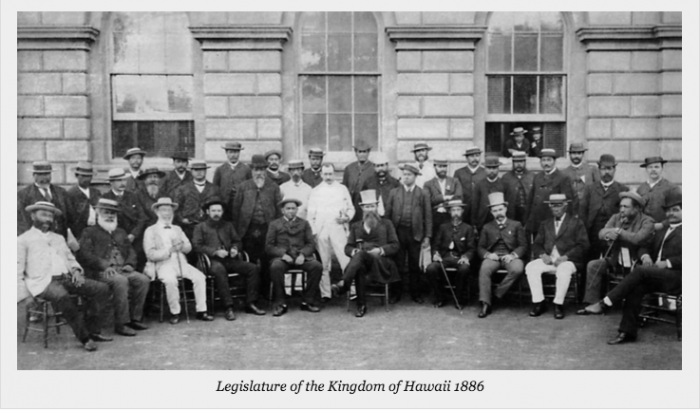

The Hawaiian Islands was never an incorporated territory of the United States and is currently under an illegal and prolonged occupation. The Hawaiian Kingdom was recognized as an independent and sovereign State since November 28, 1843 by joint proclamation of Great Britain and France. As a result of the United States’ recognition of Hawaiian independence, the Hawaiian Kingdom entered into a Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation, Dec. 20th 1849 (9 U.S. Stat. 977); Treaty of Commercial Reciprocity, Jan. 13th 1875 (19 U.S. Stat. 625); Postal Convention Concerning Money Orders, Sep. 11th 1883 (23 U.S. Stat. 736); and a Supplementary Convention to the 1875 Treaty of Commercial Reciprocity, Dec. 6th 1884 (25 U.S. Stat. 1399).

The Hawaiian Kingdom also entered into treaties with Austria-Hungary, June 18, 1875; Belgium, Oct. 4, 1862; Bremen, March 27, 1854; Denmark, Oct. 19th 1846; France, July 17, 1839, March 26, 1846, Sep. 8, 1858; French Tahiti, Nov. 24, 1853; Germany, March 25, 1879; Great Britain, Nov. 13, 1836 and March 26, 1846; Great Britain’s New South Wales, March 10, 1874; Hamburg, Jan. 8, 1848; Italy, July 22, 1863; Japan, Aug. 19, 1871, Jan. 28, 1886; Netherlands, Oct. 16, 1862; Luxembourg, Oct. 16, 1862; Portugal, May 5, 1882; Russia, June 19, 1869; Samoa, March 20, 1887; Spain, Oct. 9, 1863; Sweden-Norway, April 5, 1855; and Switzerland, July 20, 1864.

Unable to procure a treaty of cession from the Hawaiian Kingdom government acquiring the Hawaiian Islands as required by international law, Congress enacted a Joint Resolution To provide for annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States, which was signed into law by President McKinley on July 7, 1898 during the Spanish-American War (30 U.S. Stat. 750) as a war measure. Congressional laws have no extraterritorial effect and are confined to United States territory.

The Hawaiian Kingdom came under military occupation on August 12, 1898 at the height of the Spanish-American War in order to reinforce and supply troops that have been occupying the Spanish colonies of Guam and the Philippines since May 1, 1898. Following the close of the Spanish-American War by the Treaty of Paris signed December 10, 1898 (30 U.S. Stat. 1754), U.S. troops remained in the Hawaiian Islands and continued its occupation to date in violation of international law.

U.S. War Department General Orders no. 101 (July 18, 1898) regulated U.S. troops when it began the occupation of the Hawaiian Islands on August 12, 1898. General Orders no. 101 mandated the Commander of U.S. troops to administer the laws of the occupied territory, being the civil and penal laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. This order was not complied with. Administration of the laws of the occupied State was codified by Article 43, 1899 Hague Convention, II (32 U.S. Stat. 1803), and then superseded by Article 43, 1907 Hague Convention, IV (36 U.S. Stat. 2227). On August 12, 1949, the United States signed and ratified the (IV) Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War of 12 August 1949 (6 U.S.T. 3516, T.I.A.S No. 3365, 75 U.N.T.S. 287).

In direct violation of the 1899 Hague Convention, II, President McKinley signed into United States law An Act To provide a government for the Territory of Hawai‘i on April 30, 1900 (31 U.S. Stat. 141); and on March 18, 1959, President Eisenhower signed into United States law An Act To provide for the admission of the State of Hawai‘i into the Union (73 U.S. Stat. 4) in direct violation of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV. These domestic laws have no extraterritorial effect and stand in direct violation of the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, the 1949 Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, IV, international humanitarian law, and customary international law—jus cogens.

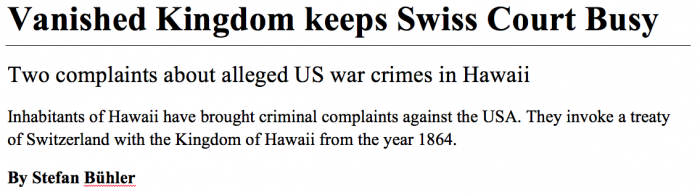

In an evidentiary ruling in State of Hawai‘i v. English (CR 14-1-0820) on March 5, 2015, where I served as defense counsel, the State of Hawai‘i Circuit Court took judicial notice of adjudicative facts that concluded the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State under international law, despite the illegal overthrow of its government by the United States of America on January 17, 1893 and the prolonged occupation since August 12, 1898. This ruling reaffirms the illegitimacy of the State of Hawai‘i and therefore its claim to be a de jure government is unfounded. State of Hawai‘i officials are also named in a pending criminal investigation for war crimes that is currently before the Swiss Federal Criminal Court Appeals Chamber under Gumapac, et al., vs. Office of the Federal Attorney General, reference no. BB.2015.36-37. A Hawaiian subject filed the first war crime complaint with the Swiss Attorney General on December 22, 2015 [2014], and a Swiss citizen filed the second complaint on January 21, 2015. Both complaints allege State of Hawai‘i officials committed war crimes of unfair trial, pillaging, and unlawful appropriation of property.

Being a self-declared entity, the State of Hawai‘i was never lawfully vested with the freehold in fee-simple to the ahupua‘a of Ka‘ohe, and therefore its so-called general lease no. S-4191 to the University of Hawai‘i dated June 21, 1968 is null and void. Consequently, all 10 subleases from the University of Hawai‘i that extend to December 31, 2033 are null and void as well, to wit:

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration dated November 29, 1974;

- Canada-France-Hawai‘i Telescope Corporation dated December 18, 1975;

- Science Research Council dated January 21, 1976;

- California Institute of Technology dated December 20, 1983;

- Science and Engineering Research Council dated February 10, 1984;

- California Institute of Technology dated December 30, 1985;

- Associated Universities, Inc., dated September 28, 1990;

- National Astronomical Observatory of Japan dated June 5, 1992;

- National Science Foundation dated September 26, 1994; and

- Smithsonian Institution dated September 28, 1995.

Therefore, the proposed University of Hawai‘i sublease to TMT International Observatory, LLC, would also be considered null and void.

The funders for the construction of the 30-meter telescope who are not the principal partners are accomplices to the principal partners’ war crime of destruction of an occupied State’s property. On April 6, 2015, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced the Canadian government’s intent to provide nearly $250 million dollars over the next decade to assist in the destruction. The Canadian government’s involvement would be a war crime as defined under Article 6(3) of Canada’s Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act (2000), which is similar to Switzerland’s legislation implementing the International Criminal Court Rome Statute into the Swiss Criminal Code in 2010. I will be providing a copy of this cease and desist to the Canadian Department of Justice, Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Section.

Thank you for your anticipated cooperation.

Very truly yours,

DEXTER K. KA‘IAMA

Attorney-at-law

Encl. (hotlinks to e-documents)

cc:

Canadian Department of Justice

Prosecutor, International Criminal Court

Board of Regents, University of Hawai‘i, State of Hawai‘i

Board of Land and Natural Resources, State of Hawai‘i

Trustees, Office of Hawaiian Affairs, State of Hawai‘i

Police Department, Hawai‘i County, State of Hawai‘i

Enclosures

(Hotlinks to e-documents)

- An Act Relating to the Lands of His Majesty the King and of the Government (1848)

- War Department General Orders no. 101

- Transcript of evidentiary hearing on March 5, 2015, State of Hawai‘i v. English (CR 14-1-0820)

- Brief by Dr. David Keanu Sai, “The Continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the Legitimacy of the acting Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom (2013),” that was judicially noticed on March 5, 2015 in State of Hawai‘i v. English (CR 14-1-0820)

- War Crime Complaint filed with Swiss Attorney General on December 22, 2015 (December 7, 2015)— http://hawaiiankingdom.org/pdf/Swiss_AG_War_Crimes_Report.pdf

- Second War Crime Complaint filed with Swiss Attorney General (January 21, 2015)

- Amendment to first War Crime Complaint (January 22, 2015)

- State of Hawai‘i General Lease no. S-4191 (June 21, 1968)

- State of Hawai‘i Board of Land and Natural Resources approval of University of Hawai‘i sublease to TMT International Observatory, LLC (June 13, 2014)

Keokani Marciel is a lifelong aloha ʻāina (Hawaiian patriot) and kanaka ʻōiwi (aboriginal Hawaiian) who holds a B.S. in Nutrition Science from the University of California at Davis, and an M.S. in Exercise Science from California University of Pennsylvania. In 2008, Keokani made a career change to mathematics education, and is now beginning an actuarial career. With his background, he brings a quantitative and scientific outlook to the discourse regarding the legal status of Hawaiʻi as an occupied nation-state.

Keokani Marciel is a lifelong aloha ʻāina (Hawaiian patriot) and kanaka ʻōiwi (aboriginal Hawaiian) who holds a B.S. in Nutrition Science from the University of California at Davis, and an M.S. in Exercise Science from California University of Pennsylvania. In 2008, Keokani made a career change to mathematics education, and is now beginning an actuarial career. With his background, he brings a quantitative and scientific outlook to the discourse regarding the legal status of Hawaiʻi as an occupied nation-state.

The authorities of the Federal Judiciary are confronted with a strange case, which has the potential of straining the relations between Switzerland and the USA. What is to be clarified is nothing less than the question of whether in the view of the [Swiss] Confederation Hawaii is recognized in accordance with international law as the 50th Federal State of the USA, or whether the Kingdom of Hawaii rather still exists – albeit since 1898 under occupation. Furthermore, it is to be determined whether the USA committed war crimes in Hawaii, including against Swiss residing there – and this possibly even with the assistance of the Swiss Joe Ackermann. It is indeed a delicate dossier, which since April 9 has been with the Federal Criminal Court in Bellinzona.

The authorities of the Federal Judiciary are confronted with a strange case, which has the potential of straining the relations between Switzerland and the USA. What is to be clarified is nothing less than the question of whether in the view of the [Swiss] Confederation Hawaii is recognized in accordance with international law as the 50th Federal State of the USA, or whether the Kingdom of Hawaii rather still exists – albeit since 1898 under occupation. Furthermore, it is to be determined whether the USA committed war crimes in Hawaii, including against Swiss residing there – and this possibly even with the assistance of the Swiss Joe Ackermann. It is indeed a delicate dossier, which since April 9 has been with the Federal Criminal Court in Bellinzona. As former CEO of Deutsche Bank, the Swiss business leader was targeted by Hawaiian subjects

As former CEO of Deutsche Bank, the Swiss business leader was targeted by Hawaiian subjects