Today, January 6, 2025, Dr. Keanu Sai, as Head of the Royal Commission of Inquiry, sent a letter to Lieutenant Colonel Michael Rosner regarding the Army doctrine of command responsibility and his military duty to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a Military Government. Here is a link to the letter.

On January 1, 2025, the Royal Commission of Inquiry (“RCI”) published its War Criminal Report no. 25-0001 finding Brigadier General Tyson Y. Tahara, Commander Hawai‘i Army National Guard, guilty of the war crime by omission. BG Tahara willfully disobeyed an Army regulation, was willfully derelict in his duty to establish a military government, and failed to stop or prevent war crimes under the doctrine of command responsibility for war crimes committed against the civilian population by the imposition of American municipal laws and administrative measures. Therefore, his conduct, by omission, constitutes a war crime.

The term “guilty,” as used in the RCI war criminal reports, is defined as “[h]aving committed a crime or other breach of conduct; justly chargeable offense; responsible for a crime or tort or other offense or fault.” However, in a criminal prosecution, “guilty” is used by “an accused in pleading or otherwise answering to an indictment when he confesses to have committed the crime of which he is charged, and by the jury in convicting a person on trial for a particular crime.”

Since returning from the Permanent Court of Arbitration in December of 2000, the Council of Regency continued to expose the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an occupied State according to the rules of international humanitarian law. In that sense, the Council of Regency was guided by paragraph 495—Remedies of Injured Belligerent, U.S. Army Field Manual 27-10, which states, “[i]n the event of violation of the law of war, the injured party may legally resort to remedial action of […]: a. Publication of the facts, with a view to influencing public opinion against the offending belligerent.”

The implementation of publishing these facts was initiated when I entered the political science graduate program at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. There, I earned a master’s degree specializing in international relations and public law, in 2004, and in 2008, a Ph.D. degree on the subject of the continuity of Hawaiian Statehood while under an American prolonged belligerent occupation since January 17, 1893. These efforts prompted other master’s theses, doctoral dissertations, peer review articles and publications about the American occupation.

Moreover, this exposure, through academic research, also inspired historian Tom Coffman to change the title of his 1998 book from Nation Within: The Story of America’s Annexation of the Nation of Hawai‘i, to Nation Within—The History of the American Occupation of Hawai‘i. Coffman explained the change in his note on the second edition:

I am compelled to add that the continued relevance of this book reflects a far-reaching political, moral and intellectual failure of the United States to recognize and deal with the takeover of Hawai‘i. In the book’s subtitle, the word Annexation has been replaced by the word Occupation, referring to America’s occupation of Hawai‘i. Where annexation connotes legality by mutual agreement, the act was not mutual and therefore not legal. Since by definition of international law there was no annexation, we are left then with the word occupation.

In making this change, I have embraced the logical conclusion of my research into the events of 1893 to 1898 in Honolulu and Washington, D.C. I am prompted to take this step by a growing body of historical work by a new generation of Native Hawaiian scholars. Dr. Keanu Sai writes, “The challenge for … the fields of political science, history, and law is to distinguish between the rule of law and the politics of power.” In the history of the Hawai‘i, the might of the United States does not make it right.

As a result of the publication of facts, United Nations Independent Expert, Dr. Alfred deZayas sent a communication, from Geneva, Switzerland, to Judge Gary W.B. Chang, Judge Jeannette H. Castagnetti, and members of the judiciary of the State of Hawai‘i dated February 25, 2018. It his letter, Dr. deZayas stated:

I have come to understand that the lawful political status of the Hawaiian Islands is that of a sovereign nation-state in continuity; but a nation-state that is under a strange form of occupation by the United States resulting from an illegal military occupation and a fraudulent annexation. As such, international laws (the Hague and Geneva Conventions) require that governance and legal matters within the occupied territory of the Hawaiian Islands must be administered by the application of the laws of the occupied state (in this case, the Hawaiian Kingdom), not the domestic laws of the occupier (the United States).

The publication of facts also prompted the U.S. National Lawyers Guild (“NLG”) to adopt, in 2019, a resolution calling upon the United States of America to begin to comply immediately with international humanitarian law in its long and illegal occupation of the Hawaiian Islands. Among its positions statement, it declared the “NLG supports the Hawaiian Council of Regency, who represented the Hawaiian Kingdom at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in its efforts to seek resolution in accordance with international law as well as its strategy to have the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties comply with international humanitarian law as the administration of the Occupying State.”

Furthermore, in a letter to Governor David Ige of the State of Hawai‘i, dated November 10, 2020, the NLG called upon the governor to comply with international humanitarian by administering the laws of the occupied State. The NLG letter concluded:

As an organization committed to the mission that human rights and the rights of ecosystems are more sacred than property interests, the NLG is deeply concerned that international humanitarian law continues to be flagrantly violated with apparent impunity by the State of Hawai‘i and its County governments. This has led to the commission of war crimes and human rights violations of a colossal scale throughout the Hawaiian Islands. International criminal law recognizes that the civilian inhabitants of the Hawaiian Islands are “protected persons” who are afforded protection under international humanitarian law and their rights are vested in international treaties. There are no statutes of limitation for war crimes, as you must be aware.

We urge you, Governor Ige, to proclaim the transformation of the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties into an occupying government pursuant to the Council of Regency’s proclamation of June 3, 2019, in order to administer the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. This would include carrying into effect the Council of Regency’s proclamation of October 10, 2014 that bring the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the nineteenth century up to date. We further urge you and other officials of the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties to familiarize yourselves with the contents of the recent eBook published by the RCI and its reports that comprehensively explains the current situation of the Hawaiian Islands and the impact that international humanitarian law and human rights law have on the State of Hawai‘i and its inhabitants.

Similarly, on February 7, 2021, the International Association of Democratic Lawyers (“IADL”), a non-governmental organization (NGO) of human rights lawyers, which has special consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council (“ECOSOC”) and accredited to participate in the Human Rights Council’s sessions as Observers, passed a resolution calling upon the United States to immediately comply with international humanitarian law in its prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Islands—the Hawaiian Kingdom. In its resolution, the IADL also stated it “supports the Hawaiian Council of Regency, who represented the Hawaiian Kingdom at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in its efforts to seek resolution in accordance with international law as well as its strategy to have the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties comply with international humanitarian law as the administration of the Occupying State.”

Together with the IADL, the American Association of Jurists—Asociación Americana de Juristas (“AAJ”), also an NGO with consultative status with the United Nations ECOSOC and an accredited observer in the Human Rights Council’s sessions, sent a joint letter, dated March 3, 2022, to member States of the United Nations, on the status of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its prolonged occupation by the United States. In its joint letter, the IADL and the AAJ also “supports the Hawaiian Council of Regency, who represented the Hawaiian Kingdom at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in its efforts to seek resolution in accordance with international law as well as its strategy to have the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties comply with international humanitarian law as the administration of the Occupying State.”

On March 22, 2022, I delivered an oral statement, on behalf of the IADL and AAJ, to the United Nations Human Rights Council (“HRC”) at its 49th session in Geneva. The oral statement read:

The International Association of Democratic Lawyers and the American Association of Jurists call the attention of the Council to human rights violations in the Hawaiian Islands. My name is Dr. David Keanu Sai, and I am the Minister of Foreign Affairs ad interim for the Hawaiian Kingdom. I also served as lead agent for the Hawaiian Kingdom at the Permanent Court of Arbitration from 1999-2001 where the Court acknowledged the continued existence of my country as a sovereign and independent State.

The Hawaiian Kingdom was invaded by the United States on 16 January 1893, which began its century long occupation to serve its military interests. Currently, there are 118 military sites throughout the islands and the city of Honolulu serves as the headquarters for the Indo-Pacific Combatant Command.

For the past century, the United States has and continues to commit the war crime of usurpation of sovereignty, under customary international law, by imposing its municipal laws over Hawaiian territory, which has denied Hawaiian subjects their right of internal self-determination by prohibiting them to freely access their own laws and administrative policies, which has led to the violations of their human rights, starting with the right to health, education and to choose their political leadership.

None of the 47 HRC member States, which includes the United States, protested, or objected to the oral statement of war crimes being committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States. Under international law, acquiescence “concerns a consent tacitly conveyed by a State, unilaterally, through silence or inaction, in circumstances such that a response expressing disagreement or objection in relation to the conduct of another State would be called for.” Silence conveys consent. Since they “did not do so [they] thereby must be held to have acquiesced. Qui tacet consentire videtur si loqui debuisset ac potuisset.”

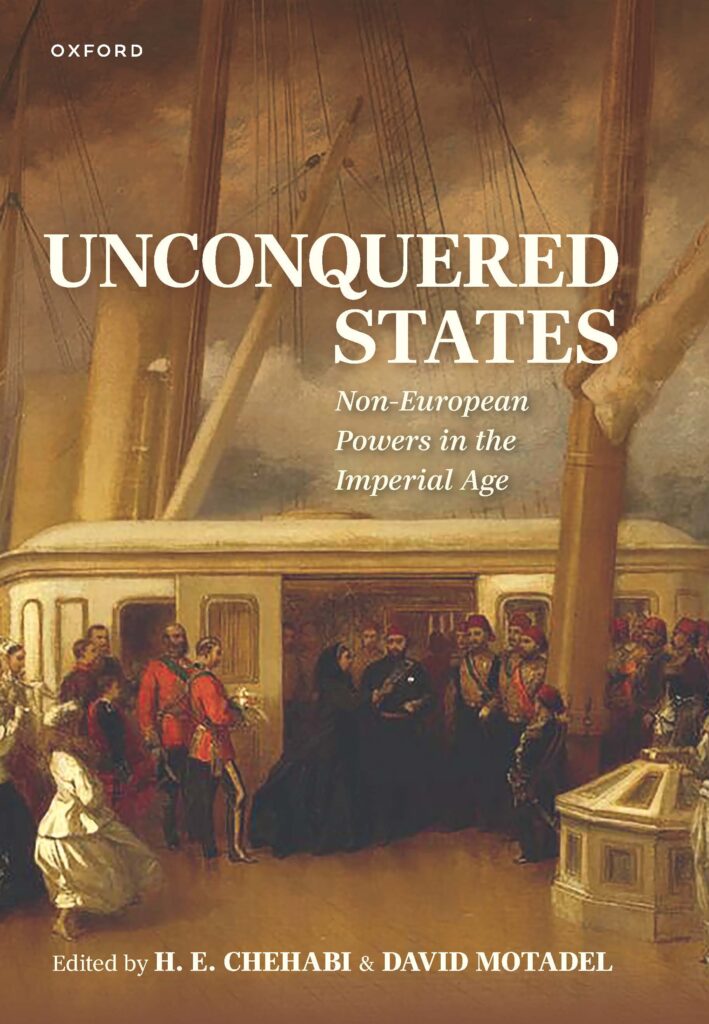

More importantly, on December 30, 2024, Oxford University Press (“OUP”) published Unconquered States—Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age, with a chapter I authored titled “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire,” which I am enclosing. OUP is a highly reputable academic publisher that acknowledges the Hawaiian Kingdom as an occupied State. The editors of the book, Professor H.E. Chehabi from Boston University and Professor David Motadel from the London School of Economics and Political Science, invited 23 scholars from around the world to contribute a chapter on an unconquered State, being a non-European Power. OUP is regarded as the gold standard for publishing academic research worldwide.

If the Hawaiian Kingdom was not an occupied State but rather the 50th State of the American union, OUP would not have allowed my chapter to be published. The cornerstone of academic research is where a scholar does not argue a position taken in their research but rather provides historical and legal evidence that cannot be refuted. In this sense, the scholar is subject to a scientific approach where a scholar’s findings and conclusions are open to rebuttal by other scholars who serve as reviewers. This is called peer review in the academic world where opinions have no place. Notably, OUP states in the book, “Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.” Thus, by OUP’s publication of my chapter, the Council of Regency has reached the pinnacle of academic publishing regarding the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom under international law on the world stage.

OUP’s release also establishes that the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom is now the longest occupation of a State in modern history. Previously, it was thought that Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and East Jerusalem, that began in 1967, was the longest occupation in modern history. As such, the Council of Regency has effectively “influen[ed] public opinion against the offending belligerent.” I conclude my chapter with:

Despite over a century of revisionist history, “the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign State is grounded in the very same principles that the United States and every other State have relied on for their own legal existence.” The Hawaiian Kingdom is a magnificent story of perseverance and continuity.

LTC Rosner, you are now the most senior Hawai‘i Army National Guard officer in the occupied Hawaiian Kingdom. Those officers above you are the subjects of war criminal reports by the RCI, and are therefore, war criminals subject to prosecution because “[c]ommanders are legally responsible for war crimes they personally commit (para. 4-24—Command responsibility under the law of war, Army Regulation 600-20).”

As such, you should assume emergency command, and as the theater commander of the occupied Hawaiian Kingdom, you must perform your duty of establishing a military government. As the theater commander, you do not standby for orders to establish a military government from any superior officer outside of the occupied Hawaiian Kingdom. Paragraph 3—Command Responsibility, FM 27-5, clearly states, the “theater commander bears full responsibility for [military government]; therefore, he is usually designated as military governor.”

Furthermore, it is the Hawai‘i Army National Guard, not the U.S. Army Pacific Command, that has the duty to establish a military government because the former is in effective control of 10,931 square miles of Hawaiian territory, while the latter is in effective control of less than 500 square miles of Hawaiian territory. Paragraph 6-12—Prerequisites and Scope of Military Occupation, FM 6-27, states:

Whether a situation qualifies as an occupation is a question of fact under LOAC. Under Article 42 of the 1907 Hague Regulations, “Territory is considered occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of a hostile army. The occupation extends only to the territory where such authority has been established and can be exercised.” Military occupation:

• Must be actual and effective; that is, the organized resistance must have been overcome, and the Occupying Power must have taken measures to establish its authority

• Requires the suspension of the territorial State’s authority and the substitution of the Occupying Power’s authority; and

• Occurs when there is a hostile relationship between the State of the invading force and the State of the occupied territory

In light of the above, as a U.S. Army officer, you have the opportunity to stand on the right side of history. As you are well aware, to not perform your duty will have dire consequences under international humanitarian law and the law of occupation.