This past Friday, August 12, 2022, District Judge Leslie Kobayashi filed a Minute Order taking under advisement the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Motion to Certify for interlocutory appeal her Order of July 28, 2022, denying the Hawaiian Kingdom’s motion for reconsideration of her previous Order granting the Federal Defendants motion to dismiss the amended complaint.

The Federal Defendants include Joseph Robinette Biden Jr., President of the United States; Kamala Harris, Vice-President of the United States; John Aquilino, Commander, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command; Charles P. Rettig, Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service; Charles E. Schumer, U.S. Senate Majority Leader; and Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives.

In their Motion to Dismiss, the Federal Defendants were claiming that this case presents a political question and that it should be dismissed. A political question means that since the United States has not recognized a nation as being sovereign and independent, the court’s will not adjudicate the case because the recognition of the sovereignty of that nation is first committed to the political branches of government. An example of a political question is Palestine. Because the United States has yet to recognize Palestine as an independent State, the federal courts deny access on matters relating to Palestine because it is a political question that the political branches have yet to recognize it.

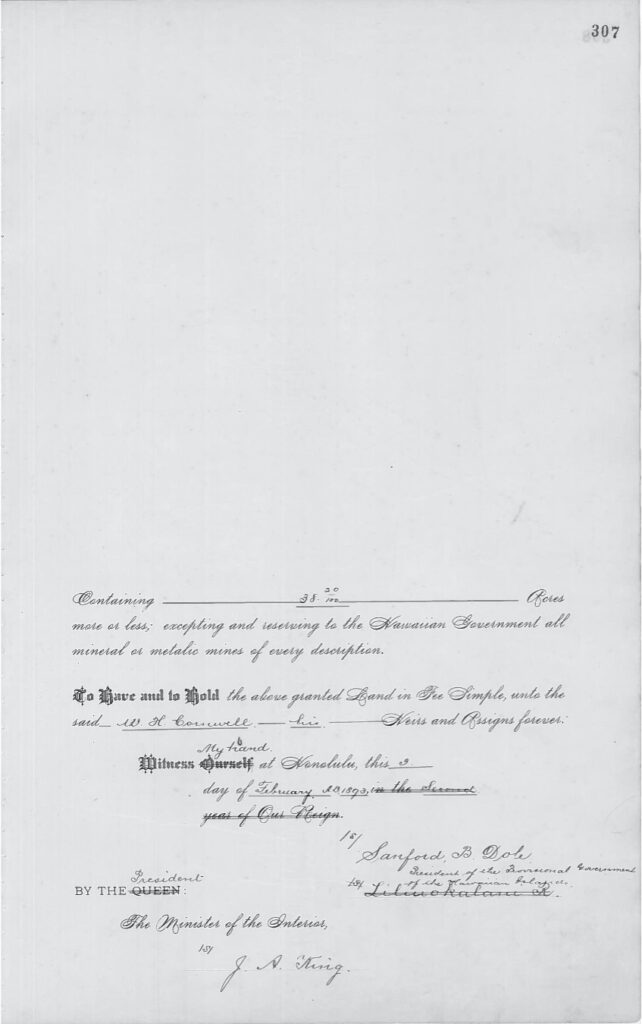

The political question doctrine, however, does not apply in this case because the United States recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign and independent State on July 6, 1844, by letter of Secretary of State John C. Calhoun on behalf of President John Tyler, and later entered into treaty relations and the establishment of embassies and consulates in the two countries.

Also, Restatement (Third) of the Foreign Relations Law of the United States, §202, comment g, states that the United States’ “duty to treat a qualified entity as a state also implies that so long as the entity continues to meet those qualifications its statehood may not be ‘derecognized.’” The United States cannot now claim that it has de-recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom. It must show a treaty where the Hawaiian Kingdom merged with the United States, which would result in its extinguishment. No such treaty exists.

In her June 9, 2022 Order granting the Federal Defendants’ motion to dismiss, Judge Kobayashi stated, “Plaintiff bases its claims on the proposition that the Hawaiian Kingdom is a sovereign and independent State. However, ‘Hawaii is a state of the United States…. The Ninth Circuit, this court, and Hawai‘i state courts have rejected arguments asserting Hawaiian sovereignty.’” She then concludes, without reference to any evidence, “Plaintiff’s claims are ‘so patently without merit that the claims require no meaningful consideration.’”

The Hawaiian Kingdom filed a Motion for Reconsideration on June 15, 2022, because Judge Kobayashi’s Order is not in line with the court decisions she cited regarding the Hawaiian Kingdom. In its motion, the Hawaiian Kingdom brought to the attention of Judge Kobayashi the Lorenzo principle that stemmed from a 1994 appeals case, State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo, that came before the State of Hawai‘i Intermediate Court of Appeals (ICA). That case centered on whether or not the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist despite the unlawful overthrow of its government by the United States on January 17, 1893.

Lorenzo lost his appeal because the ICA stated, “Lorenzo has presented no factual (or legal) basis for concluding that the Kingdom exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature.” In other words, if Lorenzo did provide the evidence of the Kingdom’s existence as a State his appeal would have been granted and his criminal conviction by the trial court overturned.

In 2002, District Court Judge David Ezra, in United States v. Goo, stated, “This court sees no reason why it should not adhere to the Lorenzo principle.” What is surprising is that Judge Kobayashi was serving at the time as the Magistrate Judge under District Court Judge Ezra who made the decision that the court would “adhere to the Lorenzo principle.” The case centered on an Order issued by Magistrate Judge Kobayashi, which Judge Ezra affirmed. Judge Kobayashi cannot simply disregard the Lorenzo principle, when in fact the Lorenzo principle was used to confirm her Order as a Magistrate Judge.

In 2004, the ICA reiterated that a defendant has to provide evidence of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence as a State and not just say it exists. In State of Hawai‘i v. Araujo, the ICA stated:

Because Araujo has not, either below or on appeal, “‘presented any factual or legal basis for concluding that the Kingdom exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature,’” (citing Lorenzo, 77 Hawai‘i at 221, 883 P.2d at 643), his point of error on appeal must fail.

Finally, in 2014, the Hawai‘i Supreme Court, in State of Hawai‘i v. Armitage, clarified this evidentiary burden. The Supreme Court stated:

Lorenzo held that, for jurisdictional purposes, should a defendant demonstrate a factual or legal basis that the Kingdom “exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature,” and that he or she is a citizen of that sovereign state, a defendant may be able to argue that the courts of the State of Hawai‘i lack jurisdiction over him or her.

When Judge Kobayashi stated in her Order granting the Federal Defendants’ motion to dismiss that the “Ninth Circuit, this court, and Hawai‘i state courts have rejected arguments asserting Hawaiian sovereignty,” this is not an accurate statement. What the courts did conclude is that the defendants in those cases did not provide any evidence of the Kingdom’s existence as a State according to the Lorenzo principle. Instead, the defendants provided argument but not any evidence to support their argument. Judge Kobayashi’s statement would appear that these courts concluded the Hawaiian Kingdom does not exist as a State, which was clearly not the case.

Despite the Hawaiian Kingdom’s attempt to draw the attention of Judge Kobayashi to the Lorenzo principle and her errors, she issued an Order on July 28, 2022, denying the Hawaiian Kingdom’s request for reconsideration. She stated, “Although Plaintiff argues there are manifest errors of law in the 6/9/22 Order, Plaintiff merely disagrees with the Court’s decision. Plaintiff’s mere disagreement, however, does not constitute grounds for reconsideration.”

Normally, when one of the parties to a lawsuit wants to appeal a decision made by a federal judge they have to wait until the case is over. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals stated, “A district court order…is not appealable [under § 1291] unless it disposes of all claims as to all parties or unless judgment is entered in compliance with Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 54(b).” In other words, an Order is appealable while a case is still pending before the district court if it is in compliance with certain rules.

Federal statute 28 U.S.C. §1292(b) allows for Orders, called interlocutory orders, to be appealable if there is a difference of opinion regarding a controlling question of law. This is precisely what Judge Kobayashi stated in her Order denying the request for reconsideration. She stated, “Plaintiff merely disagrees with the Court’s decision.” This disagreement centers on a law that is supposed to be applied by the court in these proceedings. In this case, it would be the application of the Lorenzo principle.

Laws are not only legislative enactments but also include Appellate Court and Supreme Court decisions called common law. When there is no statute or law that would apply to a particular issue, the courts are allowed to make decisions that bind the lower courts when those type of matters come before the trial courts. Until a law is enacted on that particular matter or the highest court changes its decision, the common law would continue to apply at the district court level and bind the judges in their decisions.

The Hawaiian Kingdom filed its Motion to Certify so that the Ninth Circuit can review Judge Kobayashi’s Orders. Under §1292(b), the district court judge must first certify that the request to appeal an interlocutory order to the Ninth Circuit has met certain elements. §1292(b) states:

When a district judge, in making in a civil action an order not otherwise appealable under this section, shall be of the opinion that such order involves a controlling question of law as to which there is substantial ground for difference of opinion and that an immediate appeal from the order may materially advance the ultimate termination of the litigation, he shall so state in writing in such order. The Court of Appeals which would have jurisdiction of an appeal of such action may thereupon, in its discretion, permit an appeal to be taken from such order, if application is made to it within ten days after the entry of the order.

When a motion is filed in court proceedings, the other party, in this case the Federal Defendants, will have to file a motion to oppose or not oppose the filing. Dexter Ka‘iama, Attorney General for the Hawaiian Kingdom, spoke with the Department of Justice who is representing the Federal Defendants and told them that the Hawaiian Kingdom will be filing a motion for certification and asked if they would oppose or agree with the action. They told Attorney General Ka‘iama that they would oppose it.

The Hawaiian Kingdom was planning to respond to the Federal Defendants’ filing of their opposition with additional information it had found to support its Motion to Certify. However, when Judge Kobayashi filed her Order this past Friday, she stated, “that no response to the Certification Motion is necessary,” which means the Federal Defendants will not be filing their opposition as to why they oppose the motion to certify. They merely stated to Attorney General Ka‘iama that they will oppose it.

On Sunday, August 14, 2022, the Hawaiian Kingdom filed a Supplement to its Motion to Certify with the information it intended to reply to the Federal Defendants’ filing of their opposition. In its supplement to its motion, the Hawaiian Kingdom showed that there are other laws, along with the Lorenzo principle, to be the controlling law on this topic that Judge Kobayashi disregarded.

In its recent filing, the Hawaiian Kingdom expanded on the Lorenzo principle as the common law of the State of Hawai‘i. For the past 28 years, State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo was cited by the Hawai‘i Supreme Court in 8 cases, the most recent was in 2020. The ICA cited Lorenzo in 45 cases, the most recent was in 2021.

As common law of the State of Hawai‘i, Judge Kobayashi was bound to apply it in this case because of §34 of the Federal Judiciary Act of 1789, which is codified under 28 U.S.C. §1652:

The laws of the several states, except where the Constitution or treaties of the United States or Acts of Congress otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded as rules of decision in civil actions in the courts of the United States, in cases where they apply.

Reinforcing this statute, the United States Supreme Court, in Erie R.R. v. Tompkins, stated that “federal courts are bound to follow decisions of the courts of the State in which the controversies arise.” Judge Kobayashi cannot simply disregard 28 years of decisions by the State of Hawai‘i courts that say defendants must provide evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State despite its government being unlawfully overthrown by the United States on January 17, 1893. The Hawaiian Kingdom also stated:

Further, it appears that the Court adopted a federal rule of decision to favor the United States despite its admitted illegal conduct regarding the overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893. The application of the Lorenzo principle, as the common law of the State of Hawai‘i, should not be deemed by the Court to be incompatible with federal interests because it does not promote the interest of the United States. This is problematic because the federal court did adopt the Lorenzo principle as federal law in 17 cases, but this Court adopted a rule of decision—political question doctrine, in this one instance without any basis in law or fact, that unfairly advances the interest of the United States and shields them from accountability for its admitted unlawful conduct. This gives the impression that the Court is giving one party to the controversy an unfair advantage.

The Hawaiian Kingdom concluded:

Because the Court chose to supersede the decisions of the ICA and the Hawai‘i Supreme Court regarding the evidentiary basis of Lorenzo by invoking the political question doctrine in favor of the United States, the Court should certify for interlocutory appeal so that the Ninth Circuit can address this matter in the light of §1652, Erie, and the Lorenzo principle as controlling law in this case.