On May 25, 2022, on behalf of the United States, President Joseph Biden, Vice-President Kamala Harris, Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service, Commander of the Indo-Pacific Command Admiral Aquilino, Senate Majority Leader Charles Schumer and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, the Department of Justice in Washington, D.C., filed a Response to the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Motion to Dismiss for Forum Non Conveniens.

A motion to dismiss for forum non conveniens is filed with an appellate court if the proper court of appeals is in a foreign country. In its motion the Hawaiian Kingdom is asking the Ninth Circuit Court to dismiss the appeal because the Clerk of the District Court of Hawai‘i transmitted the appeal to the Ninth Circuit in error.

When the Hawaiian Kingdom filed its Notice of Appeal with the Clerk of the United States District Court for the District of Hawai‘i on April 24, 2022, it specifically stated that the Hawaiian Kingdom was appealing to a competent Court of Appeals to be hereafter established by the United States as an Occupying Power within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom. It was the Clerk that transferred the Notice of Appeal to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco, and not the Hawaiian Kingdom.

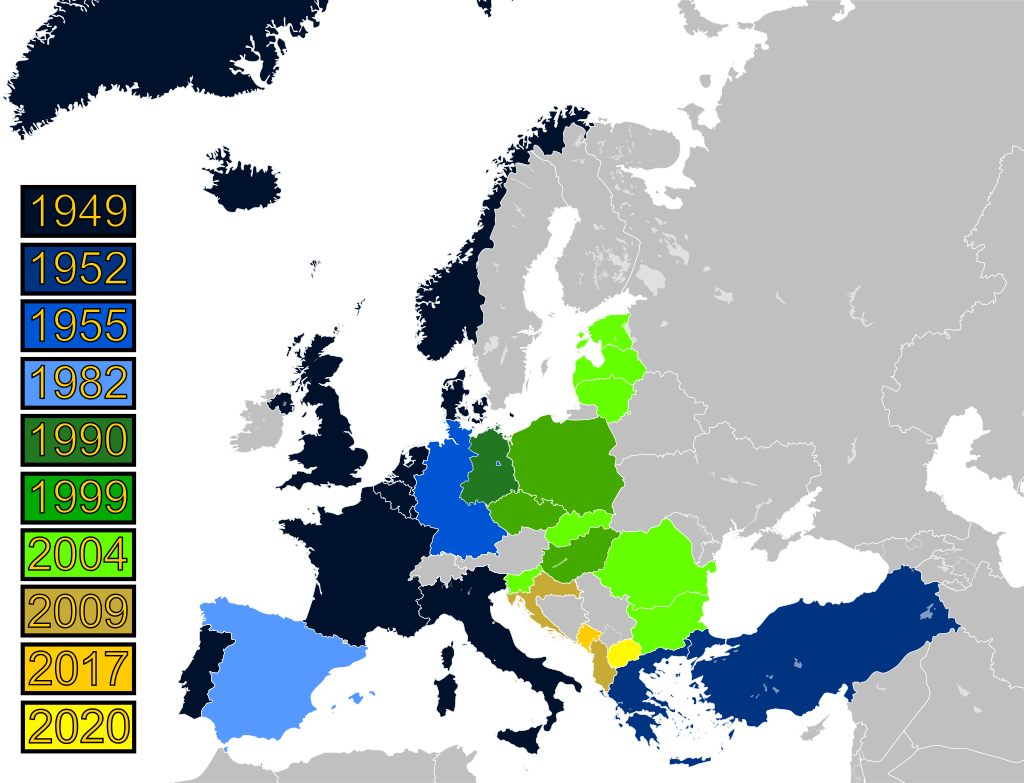

The international laws of occupation allows the Occupying Power, in this case the United States, to establish an Article II Occupation Court in the Hawaiian Kingdom’s territory as the occupying State to administer the laws of the occupied State and the international laws of occupation. The United States established an Article II Occupation Court in Germany in 1945 until 1955 when the occupation of Germany ended.

After receiving the appeal, the Clerk of the Ninth Circuit issued an Order for the Hawaiian Kingdom to file within 21 days a motion “for voluntary dismissal of the appeal or show cause why it should not be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction.” Federal appeals can only be made after the case is over at the trial court level. District Court Judge Leslie Kobayashi did not terminate the proceedings in Hawaiian Kingdom v. Biden.

The Hawaiian Kingdom filed its Motion to Dismiss for Forum Non Conveniens, but in doing so asked the Ninth Circuit Court to comply with the Lorenzo principle, which is federal common law, and compel the United States to show evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom does not exist as a matter of international law. The Hawaiian Kingdom is “show[ing] cause why it should not be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction.” The Lorenzo principle has a direct nexus to a 1994 appeal that came before the State of Hawai‘i Intermediate Court of Appeals called State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo. The Appellate Court stated:

Lorenzo appeals, arguing that the lower court erred in denying his pretrial motion (Motion) to dismiss the indictment. The essence of the Motion is that the [Hawaiian Kingdom] (Kingdom) was recognized as an independent sovereign nation by the United States in numerous bilateral treaties; the Kingdom was illegally overthrown in 1893 with the assistance of the United States; the Kingdom still exists as a sovereign nation; he is a citizen of the Kingdom; therefore, the courts of the State of Hawai‘i have no jurisdiction over him. Lorenzo makes the same argument on appeal. For the reasons set forth below, we conclude that the lower court correctly denied the Motion.

Lorenzo became a precedent case on the subject of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence as a State in State of Hawai‘i courts, and is known in the United States District Court in Hawai‘i, since 2002, as the Lorenzo principle. The Lorenzo principle placed the burden of proof that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State on the defendants. In 2014, the Hawai‘i Supreme Court clarified this evidentiary burden. In State of Hawai‘i v. Armitage, the Supreme Court stated:

Lorenzo held that, for jurisdictional purposes, should a defendant demonstrate a factual or legal basis that the [Hawaiian Kingdom] “exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s foreign nature[,]” and that he or she is a citizen of that sovereign state, a defendant may be able to argue that the courts of the State of Hawai‘i lack jurisdiction over him or her.

There have been seventeen federal cases that applied the Lorenzo principle, two of which came before the Ninth Circuit Court. However, a careful read of the Lorenzo decision reveals a stunning shift of who has the burden of proof and what needs to be proven. The Appellate Court in Lorenzo stated that “the court’s rationale is open to question in light of international law.” Since the determination of whether a State exists is a matter of international law, what does international law say about the existence of a State?

A rule of international law is that an established State is presumed to still exist despite its government being military overthrown. This is why the German State continued to exist after the Nazi government was militarily overthrown in 1945, and why the Japanese State continued to exist despite the military overthrow of the Japanese government, both of which ended the Second World War. In other words, the Hawaiian Kingdom, as an established State under international law, like Germany and Japan, is presumed to continue to exist despite the illegal overthrow of its government on January 17, 1893.

Because the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist, the burden was not on Lorenzo as the defendant to prove the Hawaiian Kingdom “exists,” but rather the burden is placed on the prosecutor to prove that the Hawaiian Kingdom “does not exist.” The State of Hawai‘i courts that applied the Lorenzo principle in multiple cases applied it wrong.

Also, the seventeen federal cases that applied the Lorenzo principle also had it wrong, and like the State of Hawai‘i courts are rendered unlawful because of international law, so is the United States District Court for the District of Hawai‘i. This means that all court decisions after 1893, whether the provisional government, the Republic of Hawai‘i, the Territory of Hawai‘i, the State of Hawai‘i, and since 1900, the federal courts, are void because the courts were never lawful to begin with.

Further implications of international law renders the State of Hawai‘i itself as unlawful. On this note, the Appellate Court in Lorenzo also stated that the “illegal overthrow leaves open the question whether the present governance system should be recognized” because a “State has an obligation not to recognize or treat as a state an entity that has attained the qualifications for statehood as a result of a threat or use of armed force.”

The State of Hawai‘i is a direct successor to the provisional government that was established through the “use of armed force.” In 1893, President Grover Cleveland concluded that the provisional government, which is a predecessor of the State of Hawai‘i, “owes its existence to an armed invasion by the United States.” Secretary of State Walter Gresham stated that “the Government of Hawaii surrendered its authority under a threat of war, until such time only as the Government of the United States, upon the facts being presented to it, should reinstate the constitutional sovereign.” In other words, the trial court that prosecuted Lorenzo and the Appellate Court that heard Lorenzo’s appeal were never lawful in the first place.

The Hawaiian Kingdom’s appeal that was forwarded to the Ninth Circuit by the Clerk of the District Court in Hawai‘i raised a very interesting twist regarding the Lorenzo principle and the legal standing of the Ninth Circuit. By making the Lorenzo principle into federal common law, which means judge made law at the federal level, the Ninth Circuit is bound by the Lorenzo principle, especially when the Ninth Circuit applied the Lorenzo principle in two cases that it heard on appeal.

Unlike the Hawai‘i District Court, which is currently unlawful until it transforms itself into an Article II Occupation Court, the Ninth Circuit is lawful, as an Article III Court, because it sits in the territory of the United States. As such, the Hawaiian Kingdom can invoke the Lorenzo principle that the Hawaiian Kingdom is presumed to continue to exist unless the United States, who is a defendant-appellee in this case, can provide evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom does not exist. Without providing a treaty of peace whereby the Hawaiian Kingdom ceded itself to the United States, the presumption of continuity remains. There is no treaty except for the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws since 1898.

Yesterday, June 2, 2022, the Hawaiian Kingdom filed its Reply to the United States response to its motion to dismiss that reiterated the Lorenzo principle and why the federal court in Hawai‘i is unlawful. And that since the Ninth Circuit is not unlawful because it sits within the territory of the United States in the city of San Francisco, it should apply the Lorenzo principle in this unique case that has now come before it.

In its Reply, the Hawaiian Kingdom has petitioned the Ninth Circuit for a writ of mandamus to compel Judge Leslie Kobayashi to transform the United States District Court in Hawai‘i into an Article II Occupation Court pursuant to the Lorenzo principle and international law. Under the All Writs Act, federal circuit courts of appeal are authorized to compel an inferior court within its circuit to do something that the law says must be done. In this case, international law requires that only Article II Occupation Courts that administer the laws of the occupied State and the law of occupation can be established in the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

With the filings of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Motion to Dismiss for Forum Non Conveniens, the United States’ Response, and the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Reply, the issue is now in the hands of the Ninth Circuit for a decision.