On January 14, 2022, the United States filed their Opposition to the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Motion for Judicial Notice of Civil Law regarding the action taken by the International Bureau of the Permanent Court of Arbitration acknowledging the Hawaiian Kingdom as a non-Contracting State to the 1907 Convention on the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes. The United States simultaneously filed a Cross-Motion to Dismiss the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Amended Complaint, which it combined with their Opposition.

Today the Hawaiian Kingdom filed two pleadings in the federal lawsuit. The first filing was its Reply to the United States Opposition to the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Motion for Judicial Notice of the Civil Law. The second filing was its Opposition to the United States Cross-Motion to Dismiss. The United States will need to file their Reply to the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Opposition by February 11, 2022. In its opening of both the Reply and the Opposition, the Hawaiian Kingdom states:

Federal Government Defendants’ (“FGDs”) opposition and cross-motion to dismiss is based entirely on the jurisdiction of this Court as an Article III Court. FGDs contend that Defendant UNITED STATES OF AMERICA is the legitimate sovereign over the Hawaiian Islands because “[t]he United States annexed Hawaii in 1898, and Hawaii entered the union as a state in 1959 [and that] [t]his Court, the Ninth Circuit, and the courts of the state of Hawaii have repeatedly ‘rejected arguments asserting Hawaiian sovereignty’ distinct from its identity as a part of the United States.” FGDs’ claims lack merit on several grounds and are an attempt to obscure, mislead and misinform this Honorable Court’s duty to apply the rule of law. Furthermore, while Plaintiff views the actions taken by this Court as a matter of due diligence regarding Plaintiff’s motion for judicial notice, which is not a dispositive motion, FGDs’ motion to dismiss, being a dispositive motion, can only be entertained after the Court possesses subject matter and personal jurisdiction as an Article II Court.

Both filings are substantially the same but because of the limited word count for the Reply, the Opposition’s word count allowed more information to be added, especially adding critical information of a conspiracy at the highest level of President McKinley’s administration to illegally seize the Hawaiian Islands for military purposes. Leading this conspiracy was the former President Theodore Roosevelt, who at the time was serving as Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Under international law today, this conspiracy would be considered an internationally wrongful act in the unilateral seizure of the territory of a sovereign and independent State.

It is important for the reader to understand this part of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s history from a legal standpoint and why the United States claims of sovereignty over the Hawaiian Islands lack any credible evidence under both international laws and United States laws. These legal proceedings have cleared the “smoke and mirrors” that the United States has relied on in claiming Hawai‘i is the 50th State of the Federal Union. It has forced the United States to admit its claim over the Hawaiian Islands is “only” by virtue of a joint resolution of annexation. Not by conquest and not by prescription, which is lapse of time. But by a joint resolution, which, as a congressional action, has no force and effect beyond the borders of the United States.

In order for the readers to understand the scope and magnitude of the legal consequences of the United States’ actions in its prolonged and illegal occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, here follows the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Reply and Opposition in its entirety. The footnotes have been omitted but can be retrieved in the filings.

********************************

II. UNITED STATES RECOGNITION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM AS A STATE AND ITS GOVERNMENT PREDATES 1898

The legal status of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State predates, not postdates, 1898. FGDs omit in their pleading that President John Tyler on July 6, 1844, explicitly recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State by letter from Secretary of State John C. Calhoun to the Hawaiian Commission. This was confirmed by the arbitral tribunal in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom:

[I]n the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.

The recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State was also the recognition of its government—a constitutional monarchy, as its agent. Successors in office to King Kamehameha III, who at the time of the United States recognition was King of the Hawaiian Kingdom, did not require diplomatic recognition. These successors included King Kamehameha IV in 1854, King Kamehameha V in 1863, King Lunalilo in 1873, King Kalākaua in 1874, and Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1891.

The legal doctrines of recognition of new governments only arise “with extra-legal changes in government” of an existing State. Successors to King Kamehameha III were not established through “extra-legal changes,” but rather under the constitution and laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. According to Professor Peterson,

A government succeeding to power according to the constitution, basic law, or established domestic custom is assumed to succeed as well to its predecessor’s status as international agent of the state. Only if there is legal discontinuity at the domestic level because a new government comes to power in some other way, as by coup d’état or revolution, is its status as an international agent of the state open to question.

On January 17, 1893, by an act of war, the United States unlawfully overthrew the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom. President Grover Cleveland entered into an executive agreement with Queen Lili‘uokalani on December 18, 1893, in an attempt to restore the government but was politically prevented from doing so by members of Congress. The failure to restore the government, however, did not affect the legal status of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State under international law.

In Texas v. White, the Supreme Court stated that a State “is a political community of free citizens, occupying a territory of defined boundaries, and organized under a government sanctioned and limited by a written constitution, and established by the consent of the governed.” The Supreme Court also stated that a “plain distinction is made between a State and the government of a State.” The Supreme Court’s position is consistent with international law where the “state must be distinguished from the government. The state, not the government, is the major player, the legal person, in international law.”

According to Judge Crawford, “[p]ending a final settlement of the conflict, belligerent occupation does not affect the continuity of the State. The governmental authorities may be driven into exile or silenced, and the exercise of the powers of the State thereby affected. But it is settled that the powers themselves continue to exist. This is strictly not an application of the ‘actual independence’ rule but an exception to it…pending a settlement of the conflict by a peace treaty or its equivalent.” There is no peace treaty or its equivalent between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States.

In 1996, remedial steps were taken to restore the Hawaiian government. An acting Council of Regency was established in accordance with the Hawaiian Constitution and the doctrine of necessity to serve in the absence of the Executive Monarch. The Council was established in similar fashion to the Belgian Council of Regency after King Leopold was captured by the Germans during the Second World War. As the Belgian Council of Regency was established under Article 82 of its 1821 Constitution, as amended, in exile, the Hawaiian Council was established under Article 33 of its 1864 Constitution, as amended, in situ. According to Professor Oppenheimer, the inability for the Belgian Council to convene the Legislature under Article 82 to provide a Regent due to Germany’s belligerent occupation it “did not create any serious constitutional problems. … While this emergency obtains, the powers of the King are vested in the Belgian Prime Minister and the other members of the cabinet.”

Like Belgium, Article 33 provides that the Cabinet Council “shall be a Council of Regency, until the Legislative Assembly, which shall be called immediately shall proceed to choose by ballot, a Regent or Council of Regency, who shall administer the Government in the name of the King, and exercise all the Powers which are constitutionally vested in the King.” Like the Belgian Council, the Hawaiian Council was bound to call into session the Legislative Assembly to provide for a regency but because of the prolonged belligerent occupation it was impossible for the Legislative Assembly to function. Until the Legislative Assembly can be called into session, Article 33 provides that the Cabinet Council, comprised of the Ministers of the Interior, Foreign Affairs, Finance and the Attorney General, “shall be a Council of Regency, until the Legislative Assembly” can be called into session. The operative words are “shall” and “until.”

The Hawaiian Council was established in accordance with the domestic laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom as they existed prior to the unlawful overthrow of the previous administration of Queen Lili‘uokalani, and, therefore, did not require diplomatic recognition like the previous administrations. Hence, the FGDs are estopped, as a matter of United States practice from 1846 to 1893 and international law, from denying the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State and its government—the Council of Regency.

III. PRESUMPTION OF CONTINUITY OF THE HAWAIIAN STATE

Under international law, there “is a presumption that the State continues to exist, with its rights and obligations…despite a period in which there is…no effective, government,” and that belligerent “occupation does not affect the continuity of the State, even where there exists no government claiming to represent the occupied State.” “A presumption is a rule of law, statutory or judicial, by which finding of a basic fact gives rise to existence of presumed fact, until presumption is rebutted.” “If one were to speak about a presumption of continuity,” explains Professor Craven, “one would suppose that an obligation would lie upon the party opposing that continuity to establish the facts sustaining its rebuttal. The continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom, in other words, may be refuted only by a reference to a valid demonstration of legal rights, or sovereignty, on the part of the United States, absent of which the presumption remains.”

According to Craven, “[under international law,] as it existed at the critical date of 1898, it was generally held that a State might ceased to exist in one of three scenarios: a) By the destruction of its territory or by the extinction, dispersal or emigration of its population (a theoretical disposition). b) By the dissolution of the corpus of the State (cases include the dissolution of the German Empire in 1805-6; the partition of the Pays-Bas in 1831 or of the Canton of Bale in 1833). [And] c) By the State’s incorporation, union, or submission to another (cases include the incorporation of Cracow into Austria in 1846; the annexation of Nice and Savoy by France in 1860; the annexation of Hannover, Hesse, Nassau and Schleswig-Holstein and Frankfurt into Prussia in 1886). Of the three scenarios only the third would in principle apply to the Hawaiian situation, which occurs by an agreement that is evidenced by a valid treaty between the acquiring and the ceding State, whether in a state of peace or in a state of war. Since 1893, the Hawaiian Kingdom has been in a state of war with the United States.

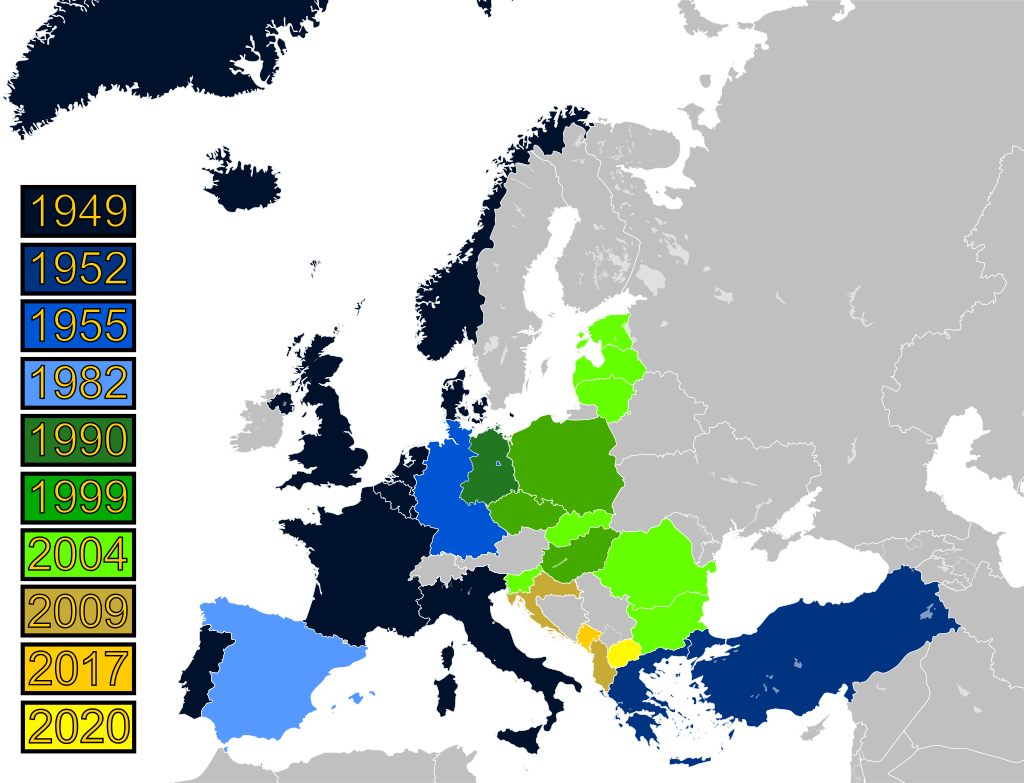

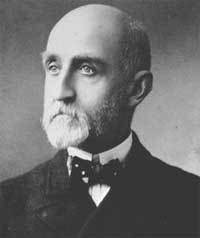

The 1898 joint resolution of annexation is not a treaty of State “incorporation” under international law but rather an internal law of the United States that stems from a failed treaty. To give the joint resolution proper context, the legislative history is important in understanding the backstory of the joint resolution. The driving force for annexation was military interest as advocated by U.S. Naval Captain Alfred Mahan.

After the United States admitted unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian Government, Mahan wrote a letter to the Editor of the New York Times where he advocated seizing the Hawaiian Islands. On January 31, 1893, he wrote that the Hawaiian Islands, “with their geographical and military importance, [is] unrivalled by that of any other position in the North Pacific.” Mahan used the Hawaiian situation to bolster his argument of building a large naval fleet. He warned that a maritime power could well seize the Hawaiian Islands, and that the United States should take that first step. He stated that to hold the Hawaiian Islands, “whether in the supposed case or in war with a European state, implies a great extension of our naval power. Are we ready to undertake this?” Mahan would have to wait four years to find an ally in President William McKinley’s Department of the Navy, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt.

Roosevelt sent a private and confidential letter, on May 3, 1897, to Mahan. He wrote, “I need not tell you that as regards Hawaii I take your views absolutely, as indeed I do on foreign policy generally. If I had my way we would annex those islands tomorrow.” Moreover, Roosevelt told Mahan that Cleveland’s handling of the Hawaiian situation was “a colossal crime, and we should be guilty of aiding him after the fact if we do not reverse what he did.” Roosevelt also assured Mahan “that Secretary [of the Navy] Long shares [their] views. He believes we should take the islands, and I have just been preparing some memoranda for him to use at the Cabinet meeting tomorrow.”

In a follow up letter to Mahan, on June 9, 1897, Roosevelt wrote that he “urged immediate action by the President as regards Hawaii. Entirely between ourselves, I believe he will act very shortly. If we take Hawaii now, we shall avoid trouble with Japan.” Eight days later, on June 16, 1897, the McKinley administration signed a treaty of “incorporation” with its American puppet—the Republic of Hawai‘i, in Washington, D.C. On the following day, Queen Lili‘uokalani submitted a formal protest to the U.S. State Department stating, “I declare such a treaty to be an act of wrong toward the native and part-native people of Hawaii, an invasion of the rights of the ruling chiefs, in violation of international rights both toward my people and toward friendly nations with whom they have made treaties, the perpetuation of the fraud whereby the constitutional government was overthrown, and, finally, an act of gross injustice to me.”

Ignoring the protest, President McKinley submitted the treaty for Senate ratification, which required a minimum of 60 votes under United States law. The Senate, however, was not convening until December 6, 1897. This prompted two Hawaiian political organizations to mobilize signature petitions protesting annexation. According to Professor Silva, the “strategy was to challenge the U.S. government to behave in accordance with its stated principles of justice and of government of the people, by the people, and for the people.” The Hawaiian Political Association (Hui Kalai‘āina) gathered over 17,000 signatures, and the Hawaiian Patriotic League (Hui Aloha ‘Āina) gathered 21,269 signatures. The last official census, done in 1890, tallied Hawaiian subjects at 48,107, and, therefore, the petitions, in fact, represented the majority of the Hawaiian citizenry.

The leaders representing the Hawaiian Patriotic League and the Hawaiian Political Association, arrived in Washington, D.C., on December 6, 1897, the same day the Senate opened its session, and were told there were 58 votes for annexation. The next day, they met with Queen Lili‘uokalani and chose her as chair of the Washington Committee. In that meeting, “they decided to present only the petitions of Hui Aloha ‘Āina because the substance of the two sets of petitions were different. Hui Aloha ‘Āina’s petition protested annexation, but the Hui Kālai‘āina’s petitions called for the monarchy to be restored. They agreed that they did not want to appear divided or as if they had different goals.”

Senators Richard Pettigrew and George Hoar met with the Committee and said they would lead the opposition in the Senate. Senator Hoar stated he would introduce opposition into the Senate and the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. “On December 9, with the delegates present, Senator Hoar read the text of the petitions to the Senate and had them formally accepted.” In the days that followed, the Committee would meet with many Senators urging them not to ratify the treaty. Two of the leading Senators for annexation were Senators Henry Cabot Lodge and John Morgan, who were both strong believers in Captain Mahan’s views on Hawai‘i.

Unbeknownst to the Queen and the Hawaiian delegates, Senators began to inquire into the military importance of annexing the Hawaiian Islands. On this matter, Senator James Kyle made a request, by letter, to Mahan, on February 3, 1898, where he wrote, “[r]ecent discussions in the Senate brought prominently to the front the question of the strategic features of the Hawaiian Islands, and in this connection many quotations have been made from your valuable and highly interesting contribution to literature in regard to these islands.”

This was war rhetoric to justify the preemptive seizure of a neutral State for military interests. It was precisely what Germany did in 1914 to justify its invasion and occupation of Luxembourg. Germany invaded Luxembourg before formally declaring war against France. German military commander, Herr von Jagow then stated, “to our great regret, the military measures which have been taken have become indispensable by the fact that we have received sure information that the French military were marching against Luxemburg. We were forced to take measures for the protection of our army and the security of our railway lines.” Herr von Jagow then issued a proclamation stating “all the efforts of our Emperor and King to maintain peace have failed. The enemy has forced Germany to draw the sword. France has violated the neutrality of Luxemburg and has commenced hostilities on the soil of Luxemburg against German troops, as has been established without a doubt.” The French protested against this German invasion and confirmed there were no French troops in Luxembourg. Thus, according to Garner, “The alleged intentions of France were merely a pretext, and the violation of Luxemburg was committed by Germany solely in her military interest and in no sense on the ground of military necessity.”

It appears the Senators were not swayed by Mahan’s position because by the time the Hawaiian Committee left Washington, D.C., on February 27, 1897, they had successfully chiseled the 58 Senators in support of annexation down to 46. Unable to garner the necessary 60 votes, the treaty failed by March, yet war with Spain was looming over the horizon, and the Hawaiian Kingdom would have to face the belligerency of the United States again. American military interests would be the driving forces behind the occupation of the islands, and Mahan’s philosophy, the guiding principles. On April 25, 1898, Congress declared war on Spain.

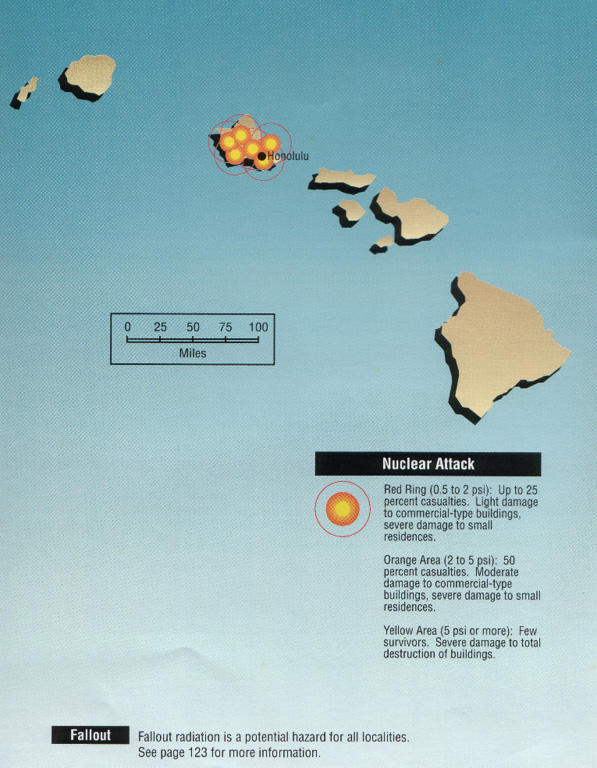

On May 1, 1898, the U.S.S. Charleston, a protect cruiser, was commissioned. Then on May 5, it was ordered to lead a convoy of 2,500 troops to reinforce Dewey in the Philippines and Guam. In a move to deliberately violate Hawaiian neutrality, the convoy set a course to re-coal and arrived in Honolulu harbor on June 1. This convoy took on 1,943 tons of coal before it left on June 4. A second convoy of troops arrived in Honolulu harbor on June 23 and took on 1,667 tons of coal. On June 8, H. Renjes, the Spanish Vice-Counsel in Honolulu, lodged a formal protest. Renjes declared, “In my capacity as Vice Consul for Spain, I have the honor today to enter a formal protest with the Hawaiian Government against the constant violations of Neutrality in this harbor, while actual war exists between Spain and the United States of America.”

The U.S. gave formal notice to the other powers of the existence of war so that these powers could proclaim neutrality, yet the United States was also violating the neutrality of the Hawaiian Kingdom at that time. From Professor Bailey’s view, the position taken by the United States “was all the more reprehensible in that she was compelling a weak nation to violate the international law that had to a large degree been formulated by her own stand on the Alabama claims. Furthermore, in line with the precedent established by the Geneva award, Hawaii would be liable for every cent of damage caused by her dereliction as a neutral, and for the United States to force her into this position was cowardly and ungrateful.” Bailey also wrote, “At the end of the war, Spain or a cooperating power would doubtless occupy Hawaii, indefinitely if not permanently, to insure payment of damages with the consequent jeopardizing of the defenses of the Pacific Coast.”

On May 4, Representative Francis Newlands submitted a joint resolution for the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to the House Committee on Foreign Affairs. On May 17, the joint resolution was reported out of the Committee without amendment and headed to the floor of the House of Representatives. The joint resolution’s accompanying Report justified the congressional action to seize the Hawaiian Islands as a matter of military interest, which was advocated by Mahan.

The Congressional record clearly showed that when the joint resolution of annexation reached the floor of the House of Representatives, members of Congress knew the limitations of congressional laws. Representative Thomas H. Ball emphatically stated, “[t]he annexation of Hawaii by joint resolution is unconstitutional, unnecessary, and unwise. …Why, sir, the very presence of this measure here is the result of a deliberate attempt to do unlawfully that which can not be done lawfully.” When the resolution reached the Senate, Senator Augustus Bacon sarcastically remarked that the “friends of annexation, seeing that it was not possible to make this treaty in the manner pointed out by the Constitution, attempted then to nullify the provision in the Constitution by putting that treaty in the form of a statute, and here we have embodied the provisions of the treaty in the joint resolution which comes to us from the House.” Senator William Allen added, “[t]he Constitution and the statutes are territorial in their operation; that is, they can not have any binding force or operation beyond the territorial limits of the government in which they are promulgated.” He later reiterated, “I utterly repudiate the power of Congress to annex the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution.”

Despite these objections the Congress passed the joint resolution and President McKinley signed it into law on July 7, 1898. This notwithstanding, the Department of Justice in 1988 concluded in a legal opinion, it is “unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution. Accordingly, it is doubtful that the acquisition of Hawaii can serve as an appropriate precedent for a congressional assertion of sovereignty over an extended territorial sea.”

Since the United States failed to carry out its obligation to reinstate the Executive Monarch and her Cabinet, under the executive agreement concluded with the Cleveland administration, the McKinley administration took complete advantage of its puppet called the Republic of Hawai‘i, and deliberately violated Hawaiian neutrality during the war. This served as leverage to force the hand of Congress to pass the joint resolution purporting to annex a foreign State. This was revealed while the Senate was in secret session on May 31, 1898, where Senator Lodge argued that the “[a]dministration was compelled to violate the neutrality of those islands, that protests from foreign representatives had already been received, and complications with other powers were threatened, that the annexation or some action in regard to those islands had become a military necessity.”

The transcripts of the secret session would not be made public until January 1969, after a historian noted there were gaps in the Congressional records. The transcripts were made public after the Senate passed a resolution authorizing the U.S. National Archives to open the records. The Associated Press in Washington, D.C., reported that “the secrecy was clamped on during a debate over whether to seize the Hawaiian Islands—called the Sandwich Islands then—or merely developing leased areas of Pearl Harbor to reinforce the U.S. fleet in Manila Bay.”

In violation of international law and the treaties with the Hawaiian Kingdom, the United States maintained the insurgents’ control until the Congress could reorganize its puppet. By statute, the Congress changed the name of the Republic of Hawai‘i to the Territory of Hawai‘i on April 30, 1900. Later, on March 18, 1959, the Congress, again by statute, changed the name of the Territory of Hawai‘i to the State of Hawai‘i. According to the U.S. Supreme Court, however, “[n]either the Constitution nor the laws passed in pursuance of it have any force in foreign territory,” which renders these congressional acts ultra vires. Of significance is this Court’s Article III status that derives from Section 9(a) of the 1959 Statehood Act.

Under the maxim ex injuria jus non oritur, FGDs’ argument that “[t]he United States annexed Hawaii in 1898, and Hawaii entered the union as a state in 1959” fails to constitute “a valid demonstration of legal rights, or sovereignty, on the part of the United States.” Therefore, the United States has provided no “facts sustaining its rebuttal” of the continuity of the Hawaiian State. Furthermore, under international law, the 1898 joint resolution of annexation and the 1959 Statehood Act, are considered internationally wrongful acts, and the FGDs are estopped from asserting that it is the legitimate sovereign over the Hawaiian Islands.

IV. DEFENDANTS ARE PRECLUDED FROM INVOKING ITS INTERNAL LAW AS A JUSTIFICATION FOR NOT COMPLYING WITH ITS INTERNATIONAL OBLIGATIONS

When the United States assumed control of its installed puppet under the new title of Territory of Hawai‘i in 1900, and later the State of Hawai‘i in 1959, it surpassed “its limits under international law through extraterritorial prescriptions emanating from its national institutions: the legislature, government, and courts.” The purpose of this extraterritorial prescription was to conceal the belligerent occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom and bypass their duty to administer the laws of the occupied State in accordance with customary international law at the time, which was later codified under Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Regulations. According to Professor Benvinisti, “[t]he occupations of Hawaii, The Philippines, and Puerto Rico reflected the same unique US view on the unlimited authority of the occupant.” This extraterritorial application of American municipal laws is prohibited by the rules of jus in bello.

The occupant may not surpass its limits under international law through extra-territorial prescriptions emanating from its national institutions: the legislature, government, and courts. The reason for this rule is, of course, the functional symmetry, with respect to the occupied territory, among the various lawmaking authorities of the occupying state. Without this symmetry, Article 43 could become meaningless as a constraint upon the occupant, since the occupation administration would then choose to operate through extraterritorial prescription of its national institutions.

According to Article 27 of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, FGDs are prohibited from “invok[ing] the provisions of its internal law as justification for its failure to perform a treaty,” which is Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Regulations. Although the United States has not ratified the Vienna Convention, U.S. foreign relations law pronounced the rule that no State may invoke its internal law as justification for the nonobservance of a treaty by which it is bound. In Coplin v. United States, the Supreme Court referred to the U.S. government’s brief in Weinberger v. Rossi: “[a]though the Vienna Convention is not yet in force for the United States, it has been recognized as an authoritative source of international treaty law by the courts…and the executive branch.” The court was referring to Article 27 of the Vienna Convention. “The first sentence of article 27 gives expression to a well-established principle of international law that a State may not evade its international obligations by pleading its own law as an excuse for noncompliance.” While the Federal Rules of Civil Procedures and the Local Rules of the Court are not internal law, they are administrative rules that do not have binding force but are instructional for the purposes of these proceedings until the Court transforms itself into an Article II Court and declare these rules to be binding.

V. DISTINGUISHING THE INSTITUTIONAL JURISDICTION OF THE PERMANENT COURT OF ARBITRATION FROM THE SUBJECT MATTER JURISDICTION OF THE LARSEN ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL

FGDs erred when they stated that “[c]entral to Professor Lenzerini’s opinion is an arbitration between an individual, Lance Larsen, and the Plaintiff before the Permanent Court of Arbitration (“PCA”) at the Hague, which Plaintiff and Professor Lenzerini believe is a tacit acknowledgment of Plaintiff’s status as a sovereign entity. However, the final arbitral award from the PCA in this dispute, issued on February 5, 2001, explicitly stated that, ‘in the absence of the United States of America [as a party] the Tribunal can neither decide that Hawaii is not part of the USA, nor proceed on the assumption that it is not.’”

Plaintiff is puzzled by this statement, given Plaintiff’s previous pleadings clearly distinguishes between the institutional jurisdiction of the PCA and the subject matter jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal. What are the undisputed facts is that a notice of arbitration was filed by Larsen’s counsel with the International Bureau of the PCA on November 8, 1999, and that six months later the International Bureau, by virtue of Article 47 of the 1907 Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes (“1907 Convention”), established the arbitral tribunal on June 9, 2000. Professor Lenzerini, in his opinion attached to Plaintiff’s motion for judicial notice, addressed the actions taken by the International Bureau of the PCA prior to the formation of the arbitral tribunal, which the civil law tradition explains from an evidentiary standpoint, and not the arguments of the arbitral tribunal, which did not have subject matter jurisdiction because of the indispensable third-party rule. Without the Hawaiian Kingdom being a juridical fact, the International Bureau could not have completed the juridical act of establishing the arbitral tribunal in the first place.

The institutional jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (“ICC”) was also recently the central issue relating to the “Situation in the State of Palestine.” Like Article 47 of the 1907 Convention, Article 12(2)(a) of the Rome Statute grants the ICC the authority to “exercise its jurisdiction” to investigate international crimes within the territory of a State Party to the Statute. Professor Malcolm Shaw authored an amicus curiae brief filed with the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber I on March 16, 2020, that addressed the question of Palestinian Statehood. According to Shaw:

[W]hether or not Palestine is a state is actually critical to defining and determining the Court’s territorial jurisdiction in this matter. If Palestine is not a state, then it cannot have sovereignty over territory and cannot come within the terms of article 12 of the Statute. Thus, in the absence of clear and irrefutable evidence of Palestine’s existence as a state and taking into account the lack of an international consensus in this regard, both quantitative and qualitative, the Court cannot assert that there is such a state at this point in time.

Article 12 does not refer to the subject matter jurisdiction of an ICC trial court, but rather provides institutional jurisdiction for the Prosecutor of the ICC to investigate international crimes that may or may not go to trial. Similarly, Article 47 does not refer to the subject matter jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal, but rather provides the institutional jurisdiction for the International Bureau to form the arbitral tribunal to resolve an international dispute.

VI. CONCLUSION

The FGDs have provided no legal basis for the Court to grant FGDs’ cross-motion to dismiss. While this Court has yet to transform itself from an Article III Court to an Article II Court, the Plaintiff perceives this Court to be in a state of due diligence regarding Plaintiff’s motion for judicial notice. In the meantime, neither the Plaintiff nor the FGDs can get relief for their amended complaint and cross-motion to dismiss, respectively, until the Court possesses subject matter and personal jurisdiction as an Article II Court pursuant to Pennoyer v. Neff.

On September 30, 2021, Magistrate Judge Rom A. Trader issued an Order granting the Motion for Leave to File Amended Amicus Curiae Brief on Behalf of Nongovernmental Organizations with Expertise in International Law and Human Rights Law [ECF 90]. Amici filed their Amended Amicus Curiae Brief on October 6, 2021 [ECF 96]. Before the Court can address FGDs’ motion to dismiss it must first transform itself into an Article II Court for the reasons stated in the filed Amicus Brief, which is “trustworthy evidence of what [international] law really is.”

Therefore, this Court is bound by treaty law to take affirmative steps to transform itself into an Article II Court by virtue of Article 43 of the 1907 Hague Regulations, just as the International Bureau of the PCA established the arbitral tribunal by virtue of Article 47 of the 1907 Convention because of the juridical fact of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence as a State. This Court is bound to transform itself into an Article II Court because it is situated within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom and not within the territory of the United States. Furthermore, FGDs have provided no rebuttable evidence to the contrary other than invoking its internal laws as justification for not complying with its international obligations, which are barred by customary international law and treaty law.