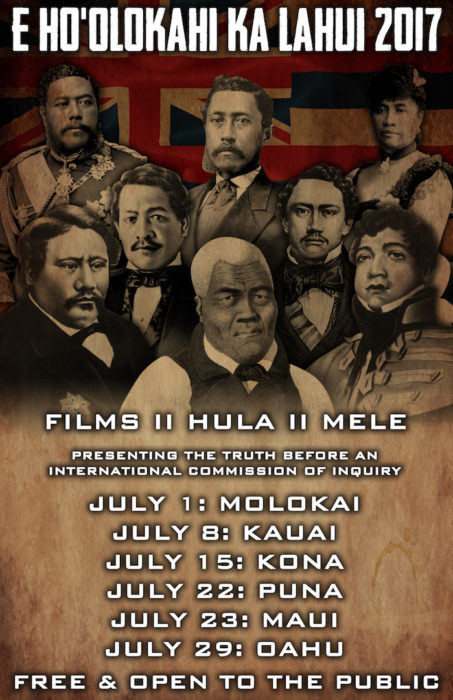

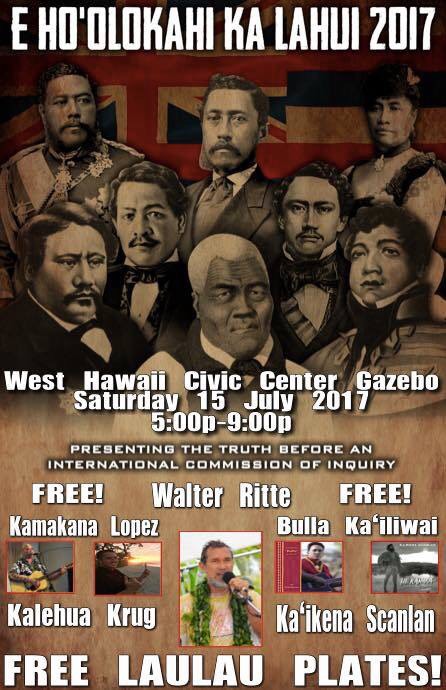

Hawaiian Independence Day Educational Conference

5

(BIVN) – “This is big,” announced Dr. Keanu Sai in the gymnasium of the Boys & Girls Club in Hilo on Saturday.

Sai, one of several featured speakers in a two day educational seminar organized in celebration of the Hawaiian holiday of La Ho‘iho‘i ‘Ea, was talking about the news that came from the National Education Association’s Annual Meeting and Representative Assembly in Boston, Massachusetts on July 4th.

A group with the Hawai‘i State Teachers Association – the NEA affiliate union representing the public school teachers of Hawaii – successfully convinced the teachers of America to approve New Business Item 37, which stated:

HSTA credited Chris Santomauro, a teacher at Kaneohe Elementary, with introducing the proposal and Uluhani Waialeale, a teacher at Kualapuu charter school on Moloka’i, for presenting an “impassioned and articulate argument in favor of the Hawaiian overthrow measure” which “swayed a majority of teachers from across the country to support it.”

“That’s big. This is not political, this is education,” Sai said as he explained the HSTA proposal to those gathered for his talk in Hilo.

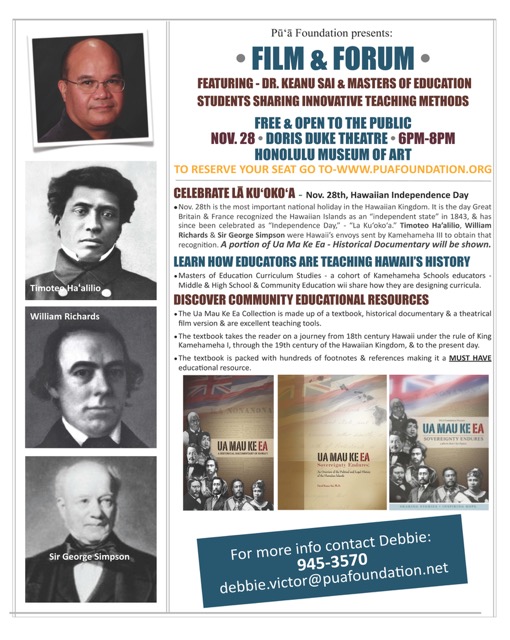

According to Sai, the HSTA Secretary/Treasurer is Amy Perruso, a teacher from Mililani High School. She was one of the first teachers to begin teaching about the illegal overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the illegal American occupation that followed. Perruso even teaches from Sai’s textbook, Ua Mau Ke Ea—Sovereignty Endures: An Overview of the Political and Legal History of the Hawaiian Islands.

“I pretty much can guarantee you that the teachers that are teaching about Hawaii’s occupation probably came through one of our classes at the University of Hawaii,” Sai said, claiming he had nothing to do with the HSTA’s plan to draw up the agenda item. “That’s the impact right there,” Sai said, “where they are taking their kuleana and maximizing it.”

Ever since Sai’s first trip to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 2001, where he represented the Hawaiian Kingdom government in the Larsen v the Hawaiian Kingdom case, Sai has made the education of Hawaii’s people his top priority.

Now, inspired by stories like the one of the HSTA in Boston, Sai feels affirmed that “it’s time to go fact-finding.”

“I think the time is right. Let’s enter into an agreement with Lance Larsen, go fact-finding,” Sai said, adding that during the 2001 proceedings before the the Permanent Court of Arbitration, the tribunal “didn’t say you can create the fact-finding within 20 years. It said all it needs is an agreement.”

Sai said two of the arbitrators are now sitting judges on the International Court of Justice.

“So, what we’re going to do is convene the original arbitrators who made the statement to be that Commission of Inquiry,” Sai said. “Because I found out that sitting judges on the International Court of Justice can also serve as arbitrators and commissioners at the permanent Court of Arbitration.”

Commissions of inquiry under the auspices of the Permanent Court serve in a similar capacity as grand juries, Sai told the audience. Commissions of Inquiry not only review sets of facts, but also assign responsibilities regarding these facts. That could be civil liability or criminal liability in international law, Sai said.

To date there have only been five International Commission’s of Inquiry, Sai said. The first was Great Britain and Russia in 1905. The most recent was Great Britain and Denmark in 1962.

“This is not… a happy time, but this is a serious time,” Sai said. “Now, what’s important here is, this agreement which will form three commissioners under the Hague Convention… they will answer the first question. First, what is the function and role of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in accordance with the basic norm and framework of international humanitarian law?”

Humanitarian law is the law of occupation and laws of war, Sai said. “Before you can address what is the role of the Hawaiian government during occupation, you have to do that in the light of what happened since 1893. You have to address what the United States did or didn’t do that got us into this situation of possible culpability of the Hawaiian government toward one of its Nationals. Is it our fault that everybody’s brainwashed?

Who’s responsible for that?”

Before the commission can answer that question, they have to “address over a hundred years of non-compliance to humanitarian law,” Sai said. “That’s how it works. Then, in light of all this… what do we do? Are we liable?”

Sai says the commission will also ask, “what are the duties and obligations of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom toward Lance Larson and – by extension – toward all Hawaiian subjects residing in Hawaii, and abroad?”

“What do we do about Lance Larson? Do we sign a reparation where we now have to pay him?” Sai asked. “Do we report the crimes to the International Criminal Court for prosecution? Where do we go?”

“Let them tell us,” Sai said. “They have the authority. We’re in the procedures. So, I don’t know what they’re going to say. I don’t. Just as I didn’t know what they would say during the proceedings of arbitration. I just know I have to take every step to protect the Hawaiian government. Because we’re in it. We’re now being put to that test.”

Sai added that once the Commission has been convened, they are going to make an important recommendation. “We’re gonna have the hearings in Hawaii,” Sai said, to a round of applause.

“I mean, this is not a political stunt. This is procedural,” Sai said. “Because… back in the year 2000, we entertained whether or not the tribunal could have their hearings in Hawaii. That was under consideration. And, after complete review, we said ‘no, there is confusion at home’. Now, I think our people are ready. They have the knowledge, they have the understanding.”

Sai again pointed to the recent HSTA victory in getting their “illegal occupation” proposal passed at the NEA meeting in Boston.

“Can you now understand,” Sai asked the crowd, “the Commission of Inquiry will probably be looking into these very issues.”

(BIVN) – As a part of the two day La Hoʻihoʻi ʻEa educational seminar held at the Boys & Girls Club in Hilo, Dr. Wille Kauai gives a talk, Understanding the impact of denationalization in the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The presenter delved into the history and issues surrounding nationality, race, and citizenship in the context of the prolonged occupation of Hawaii by the Untied States.

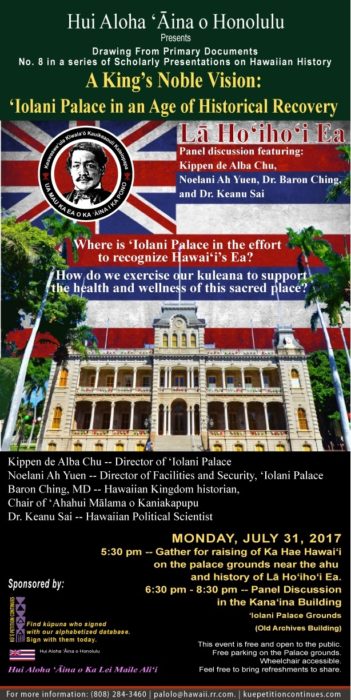

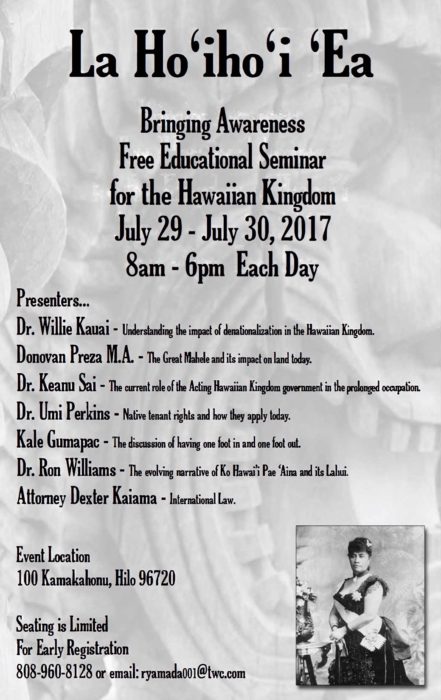

In celebration of the Hawaiian holiday Restoration Day (La Ho‘iho‘i ‘Ea) there will be an educational seminar at no charge held at the Boys and Girls Club of the Big Island at 100 Kamakahonu Street in Hilo from July 29th through the 30th. Individuals who register for the two-day seminar will receive a schedule of the time slots for each of the presenters. Everyone is encouraged to attend the full day of events.

Lunch will be provided by donation. Saturday’s menu is Kalua-pig and Cabbage, rice and macaroni salad. Sunday’s menu is Chili and Rice with Coleslaw. 1 pound containers of Kalua-pig from the Imu will be available for a $12 donation. All donations will be used to offset the cost of the two-day event.

From June 25 through July 5, 2017, the National Education Association (NEA) held its Annual Meeting and Representative Assembly in Boston, Massachusetts. The NEA is the largest labor union of 3 million members who work at every level of education that span from pre-school to university graduate programs. Formed in 1857, the NEA’s “mission is to advocate for education professionals and to unite our members and the nation to fulfill the promise of public education to prepare every student to succeed in a diverse and interdependent world.” Members include public school teachers, educational support professionals, higher education faculty and staff, and school administrators.

The Hawai‘i State Teachers Association (HSTA) is an affiliate union of the NEA whose members come from the public schools throughout Hawai‘i. Its Secretary/Treasurer, Amy Perruso, a teacher from Mililani High School was one of the first teachers to begin teaching about the illegal overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the illegal American occupation that followed. The textbook that she uses is Ua Mau Ke Ea—Sovereignty Endures: An Overview of the Political and Legal History of the Hawaiian Islands by Dr. Keanu Sai.

The Hawai‘i State Teachers Association (HSTA) is an affiliate union of the NEA whose members come from the public schools throughout Hawai‘i. Its Secretary/Treasurer, Amy Perruso, a teacher from Mililani High School was one of the first teachers to begin teaching about the illegal overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the illegal American occupation that followed. The textbook that she uses is Ua Mau Ke Ea—Sovereignty Endures: An Overview of the Political and Legal History of the Hawaiian Islands by Dr. Keanu Sai.

Perruso teaches Pre-AP Modern Hawaiian History/Participation in Democracy, AP U.S. History and A.P. Government and Politics. Commenting on the textbook Ua Mau Kea Ea, she stated, “Secondary educators in Hawai‘i are extremely fortunate to be able to access the rarest of pedagogical materials for the required Hawai‘i DOE Modern Hawaiian History course: an academically sound and well-written textbook.”

When the United States was celebrating its independence as a country on the 4th of July, the NEA’s Annual Meeting and Representative Assembly convened and for 90 minutes they took up New Business. On the agenda was New Business Item 37 introduced by the HSTA Representatives, which stated:

“The NEA will publish an article that documents the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy in 1893, the prolonged occupation of the United States in the Hawaiian Kingdom and the harmful effects that this occupation has had on the Hawaiian people and resources of the land.”

According to the HSTA Facebook, Chris Santomauro, a teacher at Kane‘ohe Elementary introduced the proposal, and Uluhani Wai‘ale‘ale, a teacher at Kualapu‘u Charter School on Moloka‘i gave an impassioned and articulate argument in favor of the proposal and it swayed a majority of teachers from across the United States to support it.

Congratulations!

There are certain standards that need to be met with regard to the terms “indigenous sovereignty” and “state sovereignty” and it begins with definitions. The former applies to indigenous peoples, while the latter applies to independent States. Current usage in Hawaiian discourse tends to conflate the two terms as if they are synonymous. This is a grave mistake that only adds to the already confusing discourse of sovereignty talk amongst Hawai‘i’s population. Instead of beginning with the definition of the terms and their difference, there is a tendency to argue native Hawaiians are an indigenous people as if it is a forgone conclusion.

Indigenous studies make a clear distinction between the terms. Corntassel and Primeau’s article “Indigenous ‘Sovereignty’ and International Law: Revised Strategies for Pursuing ‘Self-Determination,” Human Rights Quarterly 17.2 (1995) 343-365), refers to indigenous people as a “stateless group in the international system.” Defining a stateless group, Corntassel and Primeau cite Milton J. Esman’s article, “Ethnic Pluralism and International Relations,” Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism 27 (1990): 88, where he defines non-state nations as ethnic groups that do not have a patron State of their own.

While the State has its origins that date back to 1648—Treaty of Westphalia, it wasn’t until 1982 that the United Nations officially recognized indigenous groups when it formed the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations. That year the Working Group came up with its definition of indigenous populations. “Indigenous populations are composed of the existing descendants of the peoples who inhabited the present territory of a country wholly or partially at the time when persons of a different culture or ethnic origin arrived there from other parts of the world, overcame them, and, by conquest, settlement or other means reduced them to a non-dominant or colonial condition; who today live more in conformity with the particular social, economic and cultural customs and traditions that with the institutions of the country of which they now form part, under a State structure which incorporates mainly the national, social and cultural characteristics of other segments of the population which are predominant.”

According to Corntassel and Primeau the Working Group’s definition was so broad that “any non-state nation … could fit under the term ‘indigenous population (p. 347),’” which would go outside the Working Group’s focus on tribal populations. They argue that under such a broad definition any people that are non-States such as Basques, Kurds, Abkazians, Bretons, Chechens, Tibetans, Timorese, Puerto Ricans, Northern Irish, Welsh, Tamils, Madan Arabs, or Palestinians could identify themselves as “indigenous people (p. 348).”

Seven years later, in a move to limit the definition to tribes, the term “tribal peoples” was inserted in Article 1 of the 1989 Convention concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries, No. 169, adopted by the International Labor Organization. Article 1, provides: “(a) tribal peoples in independent countries [States] whose social, cultural and economic conditions distinguish them from other sections of the national community, and whose status is regulated wholly or partially by their own customs or traditions or by special laws or regulations; (b) peoples in independent countries [States] who are regarded as indigenous on account of their descent from the populations which inhabited the country, or a geographical region to which the country belongs, at the time of conquest or colonisation or the establishment of present state boundaries and who, irrespective of their legal status, retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural and political institutions.”

An “independent country” is an independent State that is a self-governing entity possessing absolute and independent legal and political authority over its territory to the exclusion of other States. All members of the United Nations are independent States. The ILO was clearly distinguishing between indigenous tribal peoples and the States they reside in. The 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples also makes that distinction in Articles 5, 8(2), 11(2), 12(2), 13(2), 14(2) (3), 15(2), 16(2), 17(2), 19, 21(2), 22(2), 24(2), 26(3), 27, 29, 30(1) (2), 32(2) (3), 33(1), 36(2), 37(1), 38, 39, 40, 42, and 46(1).

The ILO Convention covered the “what” are indigenous populations, being “tribal peoples in independent countries [States],” but it did not satisfactorily determine the “who.” This was somewhat addressed by Jose R. Martinez Cobo, Special Rapporteur of the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities, in his 1986 Report on the Study on the Problem of Discrimination against Indigenous Populations, which stated:

“Indigenous communities, peoples and nations are those which, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing on those territories, or parts of them. They form at present non-dominant sectors of society and are determined to preserve, develop and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identity, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal system (paragraph 379).”

“This historical continuity may consist of the continuation, for an extended period reaching into the present of one or more of the following factors: (a) Occupation of ancestral lands, or at least of part of them; (b) Common ancestry with the original occupants of these lands; (c) Culture in general, or in specific manifestations (such as religion, living under a tribal system, membership of an indigenous community, dress, means of livelihood, lifestyle, etc.); (e) Language (whether used as the only language, as mother-tongue, as the habitual means of communication at home or in the family, or as the main, preferred, habitual, general or normal language); (f) Residence on certain parts of the country, or in certain regions of the world; (g) Other relevant factors (paragraph 380).”

“On an individual basis, an indigenous person is one who belongs to these indigenous populations through self-identification as indigenous (group consciousness) and is recognized and accepted by these populations as one of its members (acceptance by the group) (paragraph 381).”

Throughout his report, Cobo also distinguishes between indigenous populations and the States they reside. On this note, Cobo recommends:

“States should seek to gear their policies to the wish of indigenous populations to be considered different, as well as to the ethnic identity explicitly defined by such populations. In the view of the Special Rapporteur, this should be done within a context of socio-cultural and political pluralism which affords such populations the necessary degree of autonomy, self-determination and self-management commensurate with the concepts of ethnic development (paragraph 400).”

“Countries with indigenous populations should review periodically their administrative measures for the formulation and implementation of indigenous population policy, taking particular account of the changing needs of such communities, their points of view and the administrative approaches which have met with success in countries where similar situations obtain (paragraph 404).”

In the 1996 Report of the Working Group (paragraph 31), representatives of the indigenous populations stated, “We, the Indigenous Peoples present at the Indigenous Peoples Preparatory Meeting on Saturday, 27 July 1996, at the World Council of Churches, have reached a consensus on the issue of defining Indigenous Peoples and have unanimously endorsed Sub-Commission resolution 1995/32. We categorically reject any attempts that Governments define Indigenous Peoples. We further endorse the Martinez Cobo report (E/CN.4/Sub.2/1986/Add.4) in regard to the concept of “indigenous.” The 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples does not provide for a different definition of indigenous peoples, but rather declares their rights within the States they reside.

In 2001, the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, concluded, that “in the nineteenth century the Hawaiian Kingdom existed as an independent State recognized as such by the United States of America, the United Kingdom and various other States, including by exchanges of diplomatic or consular representatives and the conclusion of treaties.” There are no indigenous people in the Hawaiian Islands because the aboriginal Hawaiians formed the State themselves, comparable to other Polynesians who formed their own States such as Samoa in 1962, and Tonga in 1970. Both States are members of the United Nations. The only difference, however, was that Hawai‘i was the first of the Polynesians to be recognized as an independent State. Furthermore, Samoans and Tongans do not refer to themselves as an “indigenous people,” but rather the citizenry of two independent States.

This is why it is paradoxical to say that natives of Hawai‘i (kanaka) are an indigenous people because it would imply they do not have a State of their own. This labeling of Hawaiian natives as indigenous people is an American narrative that has no basis in historical facts or law other than people just saying it. Rather, natives are the majority of Hawaiian subjects, being the citizenry of the Hawaiian Kingdom that has been in an unjust war by the United States since 1893.

MEDIA RELEASE

SCOTT FOSTER

Phone & Text 808-590-5880

THE THEFT OF A NATION

La Ho`iho`i Ea presents a Dramatic Re-enactment

10 am July 4, 2017, ʻIolani Palace Front Steps

HONOLULU: JUNE 29, 2017 — Americans celebrate American Independence Day on the Fourth of July every year, commemorating the Declaration of Independence and the birth of the United States of America as an independent nation in 1776. To mark an event from Hawai’i’s history, La Hoʻihoʻi Ea <http://lahoihoiea.org/history/> will observe this Fourth of July with a dramatic re-enactment of events that occurred over a century ago at ‘Iolani Palace.

Beginning at 10:00 am July 4, 2017, on the front steps of ʻIolani Palace, La Hoʻihoʻi Ea will present a dramatic re-enactment of the events that led to proclaiming into existence of the Republic of Hawaii and the subsequent installation of Sanford B. Dole as President of the Territory of Hawaii. “With Bible in hand, pistols in their pockets and American Naval troops at the ready, men gathered on the steps of ʻIolani Palace on July 4th, 1894. Invoking the name of American liberty, they dismantled the liberty of the people of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

This exciting re-enactment is free and open to the public. The script, a work in progress, has been prepared using input from several noted Hawai`i scholars and historians including writer/producer Tom Coffman <http://hawaiibookandmusicfestival.com/tom-coffman/>, Poka Laenui of Moʻoaupuni <https://mooaupuni.org/> and Dr. Lynette Cruz of La Ho`iho`i Ea. The “work in progress” event is being staged by MarshaRose Joyner. The four have worked together since 1989 under the banner of Sacred Times and Sacred Places.

CAST OF CHARACTERS

NARRATORS

Poka Laenui

Tom Coffman

THE HISTORY

On January 16, 1893, United States diplomatic and military personnel conspired with a small group of individuals to overthrow the constitutional government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and prepared to provide for annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to the United States of America under a treaty of annexation submitted to the United States Senate on February 15, 1893. Newly elected U.S. President Grover Cleveland, having received notice that the cause of the so-called revolution derived from illegal intervention by U.S. diplomatic and military personnel withdrew the treaty of annexation and appointed James H. Blount, as Special Commissioner, to investigate the terms of the so-called revolution and to report his findings.

The report concluded that the United States legation assigned to the Hawaiian Kingdom, together with United States Marines and Navy personnel, were directly responsible for the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government. The report detaild the culpability of the United States government in violating international laws and the sovereignty of the Hawaiian Kingdom, but the United States Government failed to follow through in its commitment to assist in reinstating the constitutional government of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Instead, the United States allowed five years to elapse. A new United States President, William McKinley, entered into negotiations for a second treaty of annexation on June 16, 1897, with the same individuals who participated in the illegal overthrow in 1893, but the treaty failed to be ratified by the United States Senate due to protests submitted by Her Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani and signature petitions opposing annexation signed by 21,169 Hawaiian nationals.

As a result of the Spanish-American War, the United States opted to unilaterally take the Hawaiian Islands by enacting a Congressional joint resolution on July 7, 1898, in order to utilize the Hawaiian Islands as a military base to fight the Spanish in Guam and the Philippines. The United States has remained in the Hawaiian Islands and the Hawaiian Kingdom has since been under prolonged occupation to the present, but its continuity as an independent State remains intact under international law.

Two separate camps divided Hawaiʻi’s political environment. One, a small minority, held the power of government through the landing of the U.S. military. The second, Hawaiian loyalists, supported their Hawaiian Queen Liliuokalani and their country.

The first camp wanted annexation of Hawaiʻi to the U.S., part of a larger plan to open their sugar exports to U.S. markets. They sided with American expansionists like John L. Stevens, U.S. Minister to Hawaiʻi. Hawaiian subjects, according to U.S. special investigator James Blount, were almost to the man in opposition to annexation.

U.S. troops landed on January 16, 1893 and supported a self-proclaimed “provisional government” the next day. A hurriedly drafted annexation treaty was sent to the U.S. Senate in February for ratification under Harrison’s administration, but that treaty failed. Grover Cleveland, inaugurated President in March, sent Blount to investigate the Hawaiian affair. Having received Blount’s report, Cleveland railed against U.S. conspiracy and withdrew the treaty in December.

Sanford Dole, President of the “provisional” government, was criticized for the lack of legitimacy. He convened a convention of 37 delegates, 19 appointed by him, the remainder elected by those who disavowed loyalty to Queen Liliʻuokalani and who swore allegiance to the provisional government.

Using as their backdrop the U.S. Independence day celebration, Dole’s group assembled at ʻIolani Palace at 8:00 A.M., July 4, 1894. With guns tucked out of public sight, William O. Smith, one of the early conspirators of the group, acted as master of ceremony. Dispensing with the opening prayer, apparently skittish over the proceedings taking place, Smith introduced Dole. Dole, looking down upon their members, proclaimed “the Republic of Hawaiʻi as the sovereign authority over and throughout the Hawaiian Islands.” He went on, “And I declare the Constitution framed and adopted by the Constitutional Convention of 1894 to be the constitution and the supreme law of the Republic of Hawaiʻi, and by virtue of this constitution I now assume the office and authority of president thereof.”

The constitution declared all Liliʻuokalani’s government’s lands, waters and citizens as those of the Republic.

While framing their activities around the American principle that the right of governance can only be achieved through the consent of the governed, the Republic of Hawaiʻi was declared in just the opposite manner. No ratification or consent was given the Republic by Hawaiians.

At a party in Honolulu at the U.S. Legation to celebrate July 4th that evening, Kahuku Plantation founder, J.B. Castle, proclaimed, “Americans assemble here today amidst novel and serious events to make a new declaration of independence and of principles, broader and wiser than the declaration of 1776; to make the solemn declaration that the intelligent minority in every community has the inalienable right to good government, which they are justified in securing, holding themselves responsible only to God and their own consciences for the just and proper use of power in their hands.”

Castle continued: “The inexorable law of evolution withdraws the native from his long dominance, and forces the American and his allies to the front, with a demand for a new declaration of principles. . . . the Anglo Saxon and his allies, with the best thought of civilization behind them, and trained in the best use of political machinery . . . may demonstrate to the world that they can hold the supreme power, at first, for the good of all, and gradually educate, and lead the men of other races up to their own standards of good government, and finally and safely, distribute that power among all races. . .” “We solemnly declare, with the experience of a hundred years behind us, that minorities in number have the inalienable right to good government, and they are commissioned to secure and maintain it, holding themselves responsible to God and their own consciences, for the just and proper use of the power organized and used to obtain it.” Source: Pacific Commercial Advertiser, July 5, 1894, Honolulu, Hawai`i.

Warning: This comedy video does contain vulgar language.

This is part 3 of our story trilogy presenting a recent video interview with the fascinating – and controversial – political scientist, Dr. David Keanu Sai.

HAWAII – President Donald Trump’s first weeks in office have been a whirlwind of executive action and controversy. From the Oval Office, Trump’s social media tweets – once seen as inconsequential entertainment – can now carry international ramifications. How the new president handles it all remains to be seen. But he hasn’t minced words about the situation his administration is dealing with.

“To be honest, I inherited a mess,” President Trump said during a recent press conference. “It’s a mess, at home and abroad. A mess.”

Dr. Keanu Sai agrees with him, to some extent.

“They’ve inherited war crimes,” Sai said during a recent interview with Big Island Video News. “He did. He inherited it. And he is the successor of presidents since 1893 who have inherited war crimes committed in Hawaiʻi. Violations of international law of unimaginable proportions.”

Sai earned his Ph.D. from the University of Hawaii for his work on proving the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Following the illegal overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani in 1893, there was never a legal treaty of annexation, Sai says. According to the political scientist, Hawaii is under a prolonged and illegal occupation, under international humanitarian law. Since the U.S. has not upheld the laws of the occupied state, the issue of war crimes under the Geneva Conventions comes into play.

Sai understands why many people don’t see it that way.

The fact that people in Hawaiʻi are clueless as to what Hawaiʻi was in the 19th century is the evidence of the crime. My great-grandparents were born in the Kingdom in 1880. I know nothing about the Kingdom. That wasn’t because I just didn’t know it. It’s because no one taught me. People did not teach anything because everything had to be Americanized. So, we’re the evidence of the crime. For Donald Trump and his administration, he really has nothing to do with Hawaiʻi. Nothing. Because he’s a president in America. The entities that have everything to do with our situation is the United States Pacific Command and the military here, boots on the ground. Because we’re in a sovereign country. We’re a separate country. Donald Trump is in another separate country. But he is responsible – as the president – for how the military operates here. But he also inherited all the liability of the previous presidents.”

Sai and Trump once shared similar, highly controversial positions on another presidential topic, although they arrived at their conclusions for different reasons. At the same time Donald Trump was trying to prove his predecessor in the White House was not born in the United States, Dr. Sai was lecturing on his own version of the “birther” movement.

Donald Trump, he was the birther man, right? I smiled when he first came out with ‘Barack Obama was not born in the United States’. I actually gave a presentation at NYU – also at Harvard – and it was titled ‘Why the birthers are right for all the wrong reasons.’ Barack Obama was born in Hawaiʻi. He was born at Kapiolani Hospital just about three years before I was born there. I was born in 1964. I believe he was born in 1961. He was not born in the United States, period. But I’m not saying he’s not an American. His mom was an American, so he’s an American citizen. There’s no doubt there. But he’s not natural born. Now, not being natural-born affects your status as a president, because under Article 2 of the United States Constitution the president and vice president have to be natural-born citizens. He wasn’t natural born. If he wasn’t natural-born, then he wasn’t president. If he wasn’t president, what was his administration for eight years? But see, that’s not my problem. That’s the United States’ problem.”

Does Sai believe President Trump has been fully apprised of the political situation in Hawaiʻi? He can only guess.

I would think (Trump’s administration) might want to keep this from (Trump), because he might use that to say he was correct against Barack Obama. The intelligence agencies fully apprised, I know, George W. Bush and Barack Obama. No doubt. Because there were international proceedings were taking place. Now, whether or not the intelligence group is advising Donald Trump about this? I don’t know. I would think they wouldn’t want to tell them because he’s going to take it out of context. Because, you’re talking about a powder keg here that can blow; economically, politically and criminally.”

Sai has been trying to educate the public on this subject for years, chronicling his work on the Hawaiian Kingdom blog. His has traveled the world, lecturing on this topic at the University of Cambridge, filing complaints and entering into proceedings at The Hague. He has recently initiated fact finding Commission of Inquiry as provided for by the Permanent Court of Arbitration, which arose out of the Larsen v Hawaiian Kingdom case.

My job is to fix this problem. There is no doubt that the (U.S.) State of Hawaii – although they’re illegal – they’re in control. To use a metaphor: I’m not about to have this plane called “Hawaiian” airlines, who’s flying high in the sky, disguised as if it’s “American” airlines, painted red white and blue. That paint is chipping off … This is Hawaiian airlines. We are still not in control of our plane but it is our plane. The Kingdom’s still exists. We’re not in control of it. I have to be careful that this plane doesn’t take a nosedive – economically, legally and politically – by people who are incompetent. So, I take every step very seriously to address this problem.”

Sai’s attempt to avoid a “nosedive” was recently thrust into the media spotlight. With the spending practises of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs under scrutiny, Sai’s contract to produce a manuscript on land tenure in Hawaii has become a controversy. The manuscript was never submitted for publication, although Sai was still paid $70,000 by OHA.

Sai even called one of the news stories on the controversial contract “fake news”. Something else he has in common with the Donald.

That goes to the heart as to why I refused – at this stage – to submit this manuscript that implicates all these people for war crimes, until I take the necessary steps to ensure that this plane doesn’t crash. That’s what’s important to me. Whether people believe it or not, it doesn’t matter. Can you falsify it? I’m not asking you to agree. And that’s my background. This is my approach as to how I do things. I take a very practical approach. I’m a retired (military captain). I still am an officer. These are some very hard issues and not everybody can grasp it. But there is no doubt that i know it and I’m responsible for it, because I know it. And that that’s what’s important.”