In Hawai‘i, there is much confusion regarding the principle of international law called self-determination. The term is often used in political rhetoric in Hawai‘i’s community but there is no clear understanding of the term itself and its application to Hawai‘i. Some are concerned about who will be able to vote in a plebiscite or referendum, while others believe that a plebiscite vote was already done in 1959 when Hawai‘i became the so-called 50th State of the American Union.

Let’s start off with the definition first. Self-determination is the “legal right of people to determine their own destiny in the international order.” Within this international order are different political units that comprise it. At the very top of this order is the first political unit who are the people of established States, which is also referred to as countries. The second political unit are comprised the people in non-self-governing territories, which are non-States in a colonial situation. The third political unit is comprised of Indigenous Peoples, which are tribal peoples that exist within the territory of an established State not of their own making.

Regarding the first political unit called the people or nationals of an established State, Article 1(2) of the United Nations Charter provides that one of the purposes of the United Nations is to “develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination.” Article 1 of both the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights states that “All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.”

According to Professor Cassese, this type of self-determination is where the national population of the State shall “choose their legislators and political leaders free from any manipulation or undue influence from the domestic authorities themselves.” And only when the national population of an existing State “are afforded these rights can it be said that the whole people enjoys the right of internal self-determination.” As the officers of the Hawaiian Patriotic League stated in a petition to President Cleveland on December 27, 1893, the Hawaiian nation, “for the past sixty years, had enjoyed free and happy constitutional self-government.”This means that Hawaiian subjects were enjoying, what is understood today in international law, “the right of internal self-determination” up to the American invasion and subsequent overthrow of their government on January 17, 1893.

When a State comes under the belligerent occupation by another State after its government has been overthrown, the national population of the occupied State is temporarily prevented from exercising its political rights it previously enjoyed prior to the occupation, such as choosing their “legislators and political leadership.” As Professor Craven points out, “the Hawaiian people retain a right to self-determination in a manner prescribed by general international law. Such a right would entail, at the first instance, the removal of all attributes of foreign occupation, and restoration of the sovereign rights of the dispossessed government.”

The second political unit is comprised of non-self-governing territories, such as the people of East Timor that were first under the colonial power of Portugal, then under the occupation by Indonesia. In this case, the right of self-determination is guided by the United Nations resolution 1514 called decolonization. As a dependent people who have not exercised their right of self-determination, resolution 1514 provides:

“Immediate steps shall be taken, in Trust and Non-Self-Governing Territories or all other territories which have not yet attained independence, to transfer all powers to the peoples of those territories, without any conditions or reservations, in accordance with their freely expressed will and desire, without any distinction as to race, creed or colour, in order to enable them to enjoy complete independence and freedom.”

U.N. resolution 1514 only applies to non-self-governing territories that have not achieved independence, or in other words were never an independent State. This resolution does not apply to the citizenry of existing States. The legal personality of a non-State territory is distinct from an independent State as stated in the 1975 Friendly Relations Declaration, which provides:

“The territory of a colony or other Non-Self-Governing Territory has, under the Charter, a status separate and distinct from the territory of the State administering it; and such separate and distinct status under the Charter shall exist until the people of the colony or Non-Self-Governing Territory have exercised their right of self-determination in accordance with the Charter.”

East Timor is a recent example of its people exercising their right to self-determination as defined by the United Nations for non-self-governing territories. As a former Portuguese colony that was invaded by Indonesia in 1975, East Timor exercised its right of self-determination and chose to be an independent State in a 1999 referendum overseen by the United Nations. As a result of the referendum, East Timor achieved its status as an independent State on May 20, 2002. It became the 191st member State of the United Nations. As an established State, the people of East Timor still retain their right of self-determination by choosing “their legislators and political leaders free from any manipulation or undue influence from the domestic authorities themselves.”

The Hawaiian Kingdom, as an independent State, did not lose its independence and become non-self-governing as a result of the United States illegal overthrow of its government and the ensuing occupation, just as the German and Japanese States did not lose their independence and became non-self-governing when their governments were destroyed by the Allied Powers that brought the hostilities of the Second World War to an end. Furthermore, Germany and Japan were not de-colonized when the Allied Powers ended their occupation of both their territories in the mid-1950s. These States were de-occupied according to the rules of international law, which apply with equal force to the Hawaiian Kingdom.

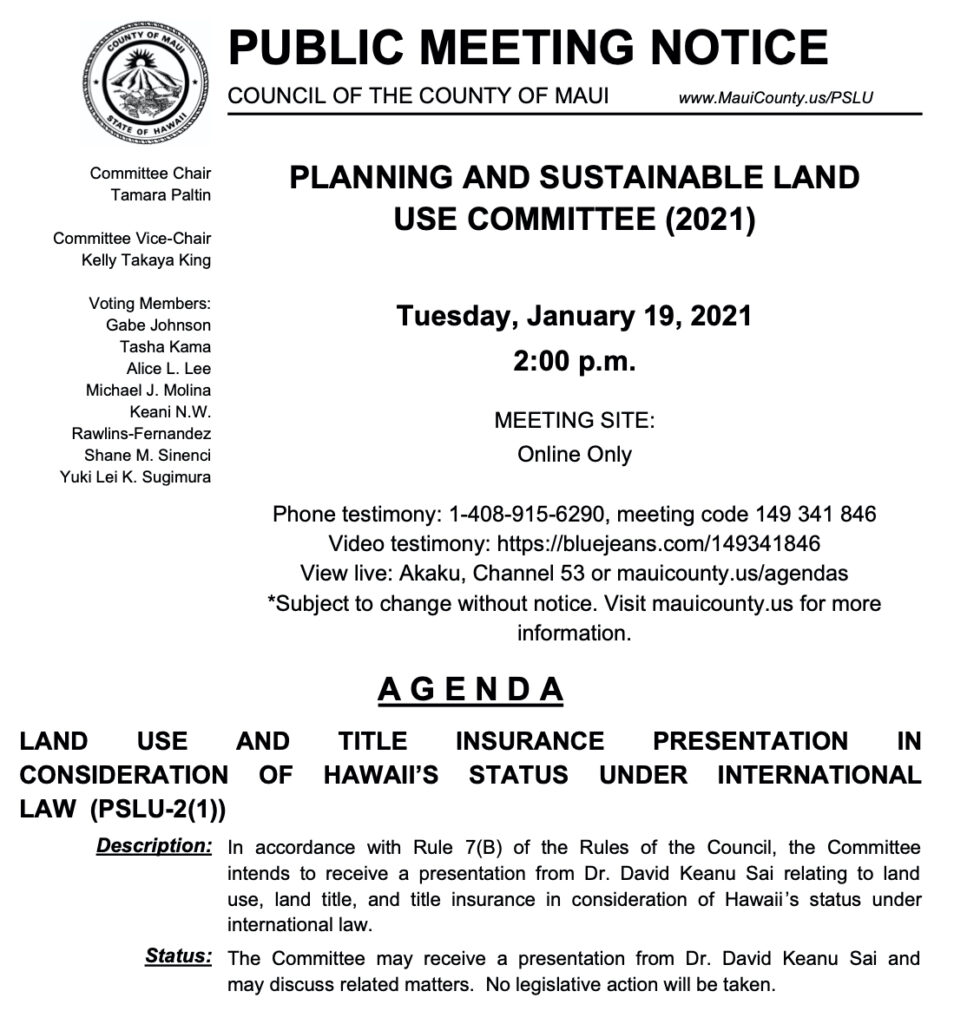

U.N. resolution 1514 does not apply to the Hawaiian situation despite the United States deliberate attempt to conceal its prolonged occupation by reporting Hawai‘i as a non-self-governing territory in 1946 under Article 73(e). The United States did not report Japan as a non-self-governing territory when it occupied Japanese territory from 1945 until 1952, or when it occupied Germany from 1945-1955. Even though the 1959 U.N. resolution 1469 (XIV) that stated the General Assembly “Expresses the opinion, based on its examination of the documentation and the explanations provided, that the people of…Hawaii have effectively exercised their right to self-determination and have freely chosen their present status” as the State of Hawai‘i, is not only an opinion and non-binding, but wrong because Hawai‘i was never a non-self-governing territory to begin with.

According to Article 13 of the U.N. Charter, the “General Assembly shall initiate studies and make recommendations for the purpose of…promoting international co-operation in the political field and encouraging the progressive development of international law and its codification.” U.N. resolutions are not a source of international law but are merely recommendations that cannot impede or alter the obligations of the United States under the law of occupation. As Judge Crawford states, “Of course, the General Assembly is not a legislature. Mostly its resolutions are only recommendations, and it has no capacity to impose new legal obligations on States.” Most people believe that the United Nations General Assembly is a legislature that enacts international law. It isn’t.

The last political unit are Indigenous Peoples. The first use of the term self-determination in Hawai‘i goes back to the 1993 congressional joint resolution apoligizing to “Native Hawaiians” for the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian government. Aside from the inaccuracies riddled throughout the congressional legislation, it stated that the Congress “apologizes to Native Hawaiians on behalf of the people of the United States for the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii on January 17, 1893 with the participation of agents and citizens of the United States, and the deprivation of the rights of Native Hawaiians to self-determination.” The Apology resolution also stated that “the indigenous Hawaiian people never directly relinquished their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people or over their national lands to the United States, either through their monarchy or through a plebiscite or referendum.”

Under international law, the term “inherent sovereignty” has no meaning. Sovereignty is vested in the Country, which is also called State sovereignty, and not in a people. Inherent sovereignty, however, is a term used in United States Federal Indian law and not international law. Its definition can be found in a 1976 law article titled “Comment: Inherent Indian Sovereignty,” published in the American Indian Law Review. The authors, Jessie Green and Susan Work, wrote:

“Inherent sovereignty is the most basic principle of all Indian law and means simply that the powers lawfully vested in an Indian tribe are those powers that predate New World discovery and have never been extinguished. Some of the powers of inherent sovereignty which have been recognized by the courts are the right to determine a form of government, the power to determine membership, the application of Indian customs, laws, and tribal jurisdiction to domestic relations and descent and distribution of property, power of taxation, exclusion of nonmembers from tribal territory, power over tribal property, rights of occupancy in tribal lands, jurisdiction over property of members, and administration of justice. Whether tribal sovereignty exists by the grace of courteous regard for the past by the courts, or by the rights of historical precedent ratified in treaties and statutes by Congress, it is an important past and present force which sets the Native American people apart from their fellow Americans.”

The apology resolution intentionally and falsely positions Native Hawaiians as a tribal group within the State of Hawai‘i that has a special relationship to the United States. The United States recognizes Native American tribes as Indigenous Peoples whose rights, under international law, come under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Article 3 of the UNDRIP states, “Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. This guarantees the right to freely determine their political condition and the right to freely pursue their form of economic, social, and cultural development.”

The United States and the State of Hawai‘i have used this type of self-determination as political rhetoric because it maintains their authority and continued presence in the Hawaiian Islands. The continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, under international law, as an independent State that has been under a prolonged occupation by the United States obliterates this false narrative. As the national population of an established State, the Hawaiian Kingdom, the right of self-determination of Hawaiian subjects will be realized when the American occupation comes to an end. The law of occupation prevents the legislature of the occupied State from convening because complete authority to temporarily administer the laws of the occupied State is with the occupying State. When the occupation comes to an end, Hawaiian political rights will be fully restored and the right of self-determination will continue to where Hawaiian subjects will “choose their legislators and political leaders free from any manipulation or undue influence from the domestic authorities themselves.” Plebiscites or referendums under the United Nations do not apply to the Hawaiian Kingdom because it is not a non-self-governing territory but rather an independent State.