As Hawaiian Independence Day (Lā Kuʻokoʻa) is approaching on Friday November 28th, KITV Island Life Live invited Dr. Keanu Sai to give some historical background and the significance of the Hawaiian Kingdom becoming an independent State on November 28, 1843. Dr. Sai will be a guest on Island Life Live for the next three Fridays leading up to November 28, 2025.

Category Archives: Education

Kamehameha Schools can Prevail in Pending Lawsuit Challenging its Admission Policy with Preference to those with Native Hawaiian Ancestry

On September 4, 2025, the Civil Beat published an article “Kamehameha Schools’ Admission Policies May Face Legal Challenge.” They reported:

A conservative mainland group whose lawsuit against Harvard ended affirmative action in college admissions is now building support in Hawai‘i to take on Kamehameha Schools’ policies that give preference to Native Hawaiian students. Students for Fair Admissions, based in Virginia, recently launched the website KamehamehaNotFair.org. It says that the admission preference “is so strong that it is essentially impossible for a non-Native Hawaiian student to be admitted to Kamehameha.” “We believe that focus on ancestry, rather than merit or need, is neither fair nor legal, and we are committed to ending Kamehameha’s unlawful admissions policies in court,” the website says.

Students for Fair Admissions won a lawsuit against Harvard University in 2023 that ruled race-based affirmative action programs in most college admissions violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Clause provides “nor shall any State … deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” Although the purpose of the Clause was to protect freed slaves after the Civil War from discrimination by the Southern States, it also applied to individuals in similar situations being treated equally by American law across all State of the Union.

Affirmative action and policies promote equal opportunity in order to counteract past discrimination and has been applied to college admissions. According to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, affirmative action is “not a type of discrimination but a justification for a policy or practice based on race, sex, or national origin. An affirmative action plan must be designed to achieve the purposes of Title VII; i.e., to break down old patterns of segregation and hierarchy and to overcome the effects of past or present practices, policies, or other barriers to equal employment opportunity.” The U.S. Supreme Court, however, in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard University, in 2023, ruled affirmative action to be unconstitutional. Kamehameha Schools is now being targeted by the same group that won its case against Harvard University.

Doe v. Kamehameha

In 2003, Kamehameha Schools faced its first legal challenge for its admission policy in Doe v. Kamehameha Schools/Bernice Pauahi Bishop Estate. The plaintiff, being an unnamed applicant that was denied admission as a student because he was not of Hawaiian ancestry, lost in the federal district court in Hawai‘i. An appeal was made to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the decision was reversed in favor of the plaintiff by a three-judge panel in 2005, where the Court held that Kamehameha Schools’ admission policy, with its preference for Native Hawaiians, constituted unlawful race discrimination under federal law. Kamehameha Schools appealed the decision to a 15-judge panel, called En Banc, at the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and the Court affirmed Kamehameha Schools admission policy as lawful on December 5, 2006. The Court concluded:

King Kamehameha I, on his death bed, is reported to have said, “Tell my people I have planted in the soil of our land the roots of a plan for their happiness.” Princess Pauahi Bishop and Her Legacy at 122. His great granddaughter, Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop, echoed that sentiment when she established, through her will, the Kamehameha Schools. Because the Schools are a wholly private K-12 educational establishment, whose preferential admissions policy is designed to counteract the significant, current educational deficits of Native Hawaiian children in Hawaii, and because in 1991 Congress clearly intended § 1981 to exist in harmony with its other legislation providing specially for the education of Native Hawaiians, we must conclude that the admissions policy is valid under 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

In its decision, the Court agreed with Kamehameha Schools position that it should review this case with “the more deferential Title VII test for evaluating affirmative action plans, with variations appropriate to the educational context.”

While the Plaintiff’s appeal was pending before the U.S. Supreme Court, Kamehameha Schools settled the lawsuit by paying $7 million. The agreement was signed in May of 2008, thus bringing the lawsuit to a close. Because the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that affirmative action in admission policies of educational institutions to be unlawful, Kamehameha Schools cannot rely on their previous position in Doe v. Kamehameha.

Radical Change in the Legal Terrain

Not only has the legal terrain changed for American law and affirmative action, the legal terrain also changed for Hawai‘i because it is now legally proven that Hawai‘i was never a part of the territory of the United States but rather an Occupied State under international law.

The writings of scholars, under international law, is regarded as law-determining and not law making. According to Professor Malcolm Shaw, a British subject, “Because of the lack of supreme authorities and institutions in the international legal order, the responsibility is all the greater upon publicists of the various nations to inject an element of coherence and order into the subject as well as to question the direction and purposes of the rules.” The United States Supreme Court understood the significance of the writings of scholars in international law. In the 1900 Paquette Habana case, the Supreme Court stated:

International law is part of our law, and must be ascertained and administered by the courts of justice of appropriate jurisdiction, as often as questions of right depending upon it are duly presented for their determination. For this purpose, where there is no treaty, and no controlling executive or legislative act or judicial decision, resort must be had to the customs and usages of civilized nations; and, as evidence of these, to the works of jurists and commentators, who by years of labor, research and experience, have made themselves peculiarly well acquainted with the subjects of which they treat. Such works are resorted to by judicial tribunals, not for the speculations of their authors concerning what the law ought to be, but for trustworthy evidence of what the law really is.

The significance of the legal opinion by Professor Matthew Craven, a British subject, on the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under international law, the legal opinion by Professor Federico Lenzerini, an Italian citizen, on the legitimacy of the Council of Regency, and the legal opinion by Professor William Schabas, a Canadian citizen, on war crimes being committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom under the American occupation since 1893, are that all three legal opinions are written by publicists who are scholars and professors in international law. Also included is Dr. Keanu Sai’s chapter “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire” in Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age that was published in December of 2024 by Oxford University Press. Oxford University Press recognizes Dr. Sai as a scholar. As such, these writings constitute a source of international law. As the U.S. Supreme Court stated, “the works of jurists and commentators [is considered] trustworthy evidence of what the law really is.”

Of note is Professor Schabas’ legal opinion on war crimes where he specifically addresses the unlawful imposition of American laws, which he refers to as the war crime of usurpation of sovereignty during occupation. American laws include administrative measures, policies, and court decisions. This renders the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and 2023 Supreme Court decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard University irrelevant. Even the U.S. Supreme Court, in United States v. Curtiss-Wright Corporation, emphatically stated:

Neither the Constitution nor the laws passed in pursuance of it have any force in foreign territory unless in respect of our own citizens …, and operations of the nation in such territory must be governed by treaties, international understandings and compacts, and the principles of international law. As a member of the family of nations, the right and power of the United States in that field are equal to the right and power of the other members of the international family. Otherwise, the United States is not completely sovereign.

Civil Rights under Hawaiian Kingdom Law

As an Occupied State, only Hawaiian Kingdom law applies over Hawaiian territory, and the Kamehameha Schools is a trust that established under and by virtue of the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. In the matter of the will of Bernice Pauahi Bishop, the Hawaiian Kingdom Supreme Court accepted the trust on March 4, 1885. The Kamehameha Schools for Boys opened in 1887 and for Girls in 1894.

During a speech at the Schools first celebration of Founder’s Day on December 19, 1888, Charles Reed Bishop, chair of the original trustees and widow of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop, stated that the Princess established the Kamehameha Schools “in order that her own people might have the opportunity for fitting themselves for such competition, and be able to hold their own in a manly and friendly way, without asking any favors which they were not likely to receive, these schools were provided for, in which Hawaiians have the preference, and which she hoped they would value and take the advantages of as fully as possible.” The speech was printed in the Daily Bulletin Weekly Summary newspaper, Honolulu (December 24, 1888).

This admission policy was established because of the intent of the Princess. It is not based on her will. Her will did not address the preference of admitting students of Hawaiian ancestry, but rather providing financial assistance “giving the preference to Hawaiians of pure or part aboriginal blood.” The significance of this speech and its publication in a newspaper makes the intent of the Princess publicly known throughout the kingdom.

Under Hawaiian Kingdom law, this admission policy of preference for students that are aboriginal Hawaiian, both pure and part, is lawful. There are three Hawaiian Kingdom Supreme Court cases that address native or aboriginal Hawaiians within the legal framework of civil rights under Hawaiian constitutional law. These cases are Naone v. Thurston, 1 Haw. 392 (1856) and Rex v. Booth, 2 Haw. 616 (1863) that are appellate cases, while Rex v. Henry H. Sawyer was a criminal trial that came before the Supreme Court at its July Term in 1859. Under Hawaiian Kingdom law, the Supreme Court served not only as an appellate court but also as a trial court.

In Rex v. Booth, the Court addressed the claim of race-based legislation, also called special legislation, which was argued by the defence to be a violation of native or aboriginal Hawaiians’ civil rights under Hawaiian laws. The defense argued, “‘It is an axiom in all constitutional Governments, that all legislative power emanates from the people; the Legislature acts by delegated authority, and only as the agent of the people ;’ that the Hawaiian Constitution was founded by the people; ‘that the Government of this Kingdom proceeds directly from the people, was ordained and established by the people,’ and that it is against all reason and justice to suppose or presume for one moment, that the native subjects of this Kingdom ever entrusted the Legislature with the power to enact such a law as that under discussion.” The Court responded, “Here is a grave mistake—a fundamental error—which is no doubt the source of much misconception. These ideas run through a large part of the case made by the defense, and much of the argument and reasoning predicated upon them, possesses no weight whatever.”

The Court discerns the legal framework of civil rights under Hawaiian constitutional law from other countries, like the United States, that have a republican form of government, which is governance of and for the people. The Hawaiian Kingdom is not a republic but rather a constitutional and limited monarchy. The Court also underscores the Hawaiian Kingdom’s approach to balancing civil rights, legislative authority, and the welfare of its native population within the framework of its Constitution. The Court clarified that civil rights and equality must be interpreted within the broader context of the Hawaiian Constitution, allowing for laws that address specific needs, such as protecting aboriginal Hawaiians, as long as they promote the welfare of the nation.

Booth provides the legal basis for the Kamehameha Schools policy to give preferential acceptance of students who are Hawaiian subjects of pure or part aboriginal blood. While the Court, in Booth, referred to special legislation, it would be called a special policy regarding aboriginal Hawaiians because the Kamehameha Schools is not a legislative body but a private trust. As a private trust, under Hawaiian Kingdon law, it must still adhere to the legal framework of civil rights under Hawaiian constitutional law and that the special policy of admission promotes the welfare of the nation. This is the Hawaiian law version of affirmative action on its terms.

How Kamehameha Schools can Prevail under Hawaiian Kingdom Law

In 1994, the Intermediate Court of Appeals heard an appeal, in State of Hawai‘i v. Lorenzo, where the defendant was challenging the jurisdiction of the trial court because of the illegality of the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government in 1893. The Appellate Court concluded that “it was incumbent on Defendant to present evidence supporting his claim. Lorenzo has presented no factual (or legal) basis for concluding that the Kingdom exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature. Consequently, his argument that he is subject solely to the Kingdom’s jurisdiction is without merit, and the lower court correctly exercised jurisdiction over him.”

Since 1994, the Lorenzo case became a precedent case that served as the basis for denying defendants’ motions to dismiss that challenged the jurisdiction of State of Hawai‘i courts because defendants provided no evidence of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence as a State under international law. Even the federal courts apply the Lorenzo case. The Supreme Court, in State of Hawai‘i v. Armitage (2014), clarified the evidentiary burden that the Lorenzo case placed upon defendants. The Court states:

Lorenzo held that, for jurisdictional purposes, should a defendant demonstrate a factual or legal basis that the [Hawaiian Kingdom] “exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature[,]” and that he or she is a citizen of that sovereign state, a defendant may be able to argue that the courts of the State of Hawai‘i lack jurisdiction over him or her.

Kamehameha Schools can prevail because it has access to all this information from the public domain that provides a “factual or legal basis” that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State “in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature,” and that it is a trust “of that sovereign state.”

Dr. Keanu Sai on KITV Island Life Live New’s Hawaiian History Month September

Last month September was “Hawaiian History” month, and Dr. Keanu Sai was invited present four episodes of Hawaiian history on KITV television show Island Life Live News. These historical episodes are covered in Dr. Sai’s chapter “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire” that was published in December of 2024 by Oxford University Press.

In his chapter, Dr. Sai covers: the legal and political history of the Hawaiian Kingdom; the evolution of governance as a constitutional monarchy; the unlawful overthrow of the government by United States troops in 1893; the prolonged American occupation since 1893; the restoration of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1997; and the recognition, by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 1999, of the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State and the Council of Regency as its provisional government.

KalikoVision Podcast in Oregon has Dr. Keanu Sai as a Guest

Today in Hawai‘i is Statehood Day or Admission Day. It is a holiday for the State of Hawai‘i set for the third Friday in August. It is supposed to commemorate the anniversary of when Hawai‘i was admitted to the American Union in 1959.

On March 18, 1959, the U.S. Congress enacted a statute called An Act To provide for the admission of the State of Hawaii into the Union. This Act of Congress began the process where Hawai‘i would eventually be admitted into the Union. On August 21, 1959, the third Friday of August, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed a proclamation making Hawai‘i the 50th State. With the unveiling of a more accurate and objectively true history, the State of Hawai‘i never legally existed in the first place.

In 1999, the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, recognized the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State since the 19th century. And in 2024, Oxford University Press published a chapter by Dr. Keanu Sai “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire,” in H.E. Chehabi and David Motadel’s book Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age. In this chapter Dr. Sai covers: the legal and political history of my country—the Hawaiian Kingdom; the evolution of governance as a constitutional monarchy; the unlawful overthrow of the government by United States troops in 1893; the prolonged American occupation since 1893; the restoration of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1997; and the recognition, by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 1999, of the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State and the Council of Regency as its provisional government. Because the Hawaiian Kingdom currently exists as a State under international law, the State of Hawai‘i cannot simultaneously exist as a State under American law.

In a recently uploaded interview on the podcast called KalikoVision, with host Kaliko Castille, Dr. Sai explains why Hawai‘i was never acquired by the United States and why the State of Hawai‘i does not legally exist.

Hawaiian Actor Jason Scott Lee Introduces 2019 Award Winning Documentary on the Council of Regency

Dr. Keanu Sai is Interviewed on Minneapolis/Saint Paul FOX 9 “The Afternoon Shift” on the Annexation of Hawai‘i

Professor Jonathan Osorio, Dean of the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s Hawai‘inuiakea School of Hawaiian Knowledge, was contacted by the host of The Afternoon Shift on FOX 9 Minneapolis/Saint Paul if he or his colleagues from the university could be on his show to talk about the joint resolution of the annexation Hawai‘i that was signed in law on July 7, 1898.

Professor Osorio responded by stating, “I am copying two professors from UH, Kamana Beamer and Keanu Sai who might be interested. But you should be aware that Hawaiʻi was never annexed by the US. Both these scholars can attest to that.” Dr. Keanu Sai was able to do the interview.

KHON Television Show “Aloha Authentic” with Kamaka Pili Interviews Dr. Keanu Sai on the Hawaiian Kingdom

VIDEOS of the Kamehameha Schools Presentation “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire: A Conversation with Dr. David Keanu Sai”

Below is the video of Dr. Keanu Sai’s presentation on his recent chapter “Hawai‘iʻs Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire” published by Englandʻs Oxford University Pressʻ Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age in December of 2024.

Below is the video of questions and answers of Dr. Keanu Sai following his presentation.

VIDEO of the Book Launch at the University of Hawai‘i of Oxford University Press’ publication of “Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age” with a Chapter on the American Occupation of Hawai‘i

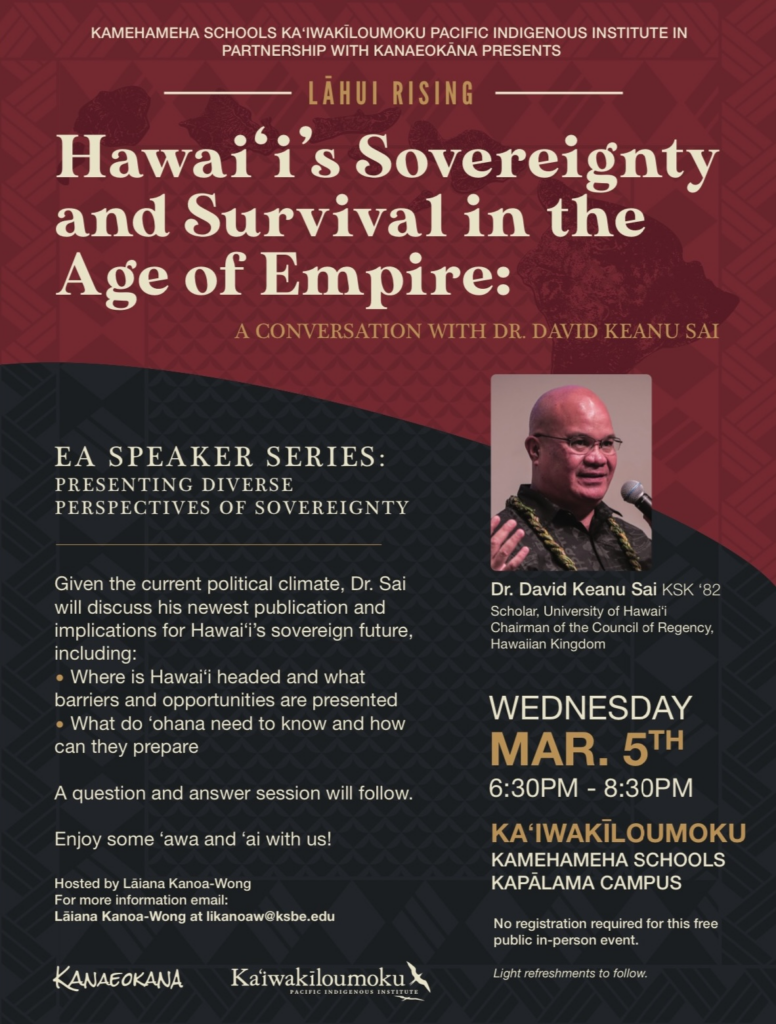

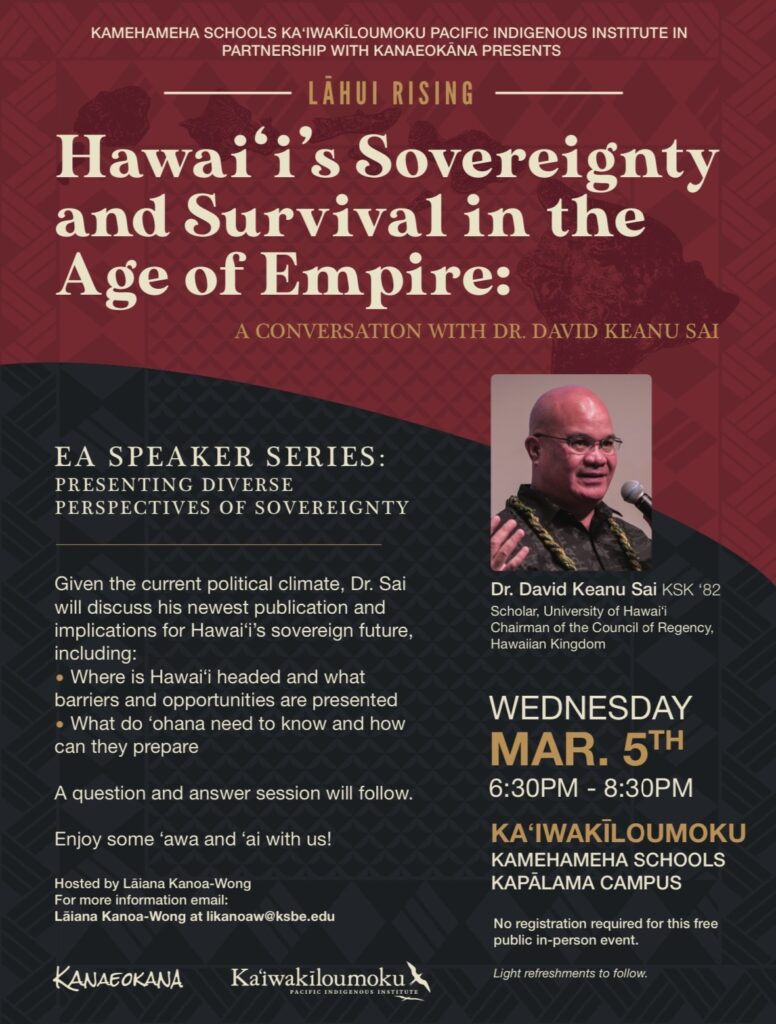

Kamehameha Schools Presents “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire: A Conversation with Dr. David Keanu Sai”

Dr. Keanu Sai, a graduate of the Kamehameha Schools Kapālama campus in 1982 has been invited by Kamehameha Schools Ka‘iwakīloumoku Pacific Indigenous Institute, in partnership with Kanaeokāna, for a presentation on March 5, 2025, with questions and answers to follow about his recent chapter “Hawai‘iʻs Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire” published by Englandʻs Oxford University Pressʻ Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age in December of 2024. No registration is required for this free public in-person event and light refreshments to follow.

The public is encouraged to attend because Dr. Saiʻs presentation will get into the operational plan for transitioning the State of Hawai‘i into a military government of Hawai‘i and the impact it will have on the population of Hawai‘i, e.g. health care, land, taxes, cost of living. The session will be recorded and uploaded on Kanaeokana’s website.

The session will be recorded and uploaded on Kanaeokana’s YouTube channel.

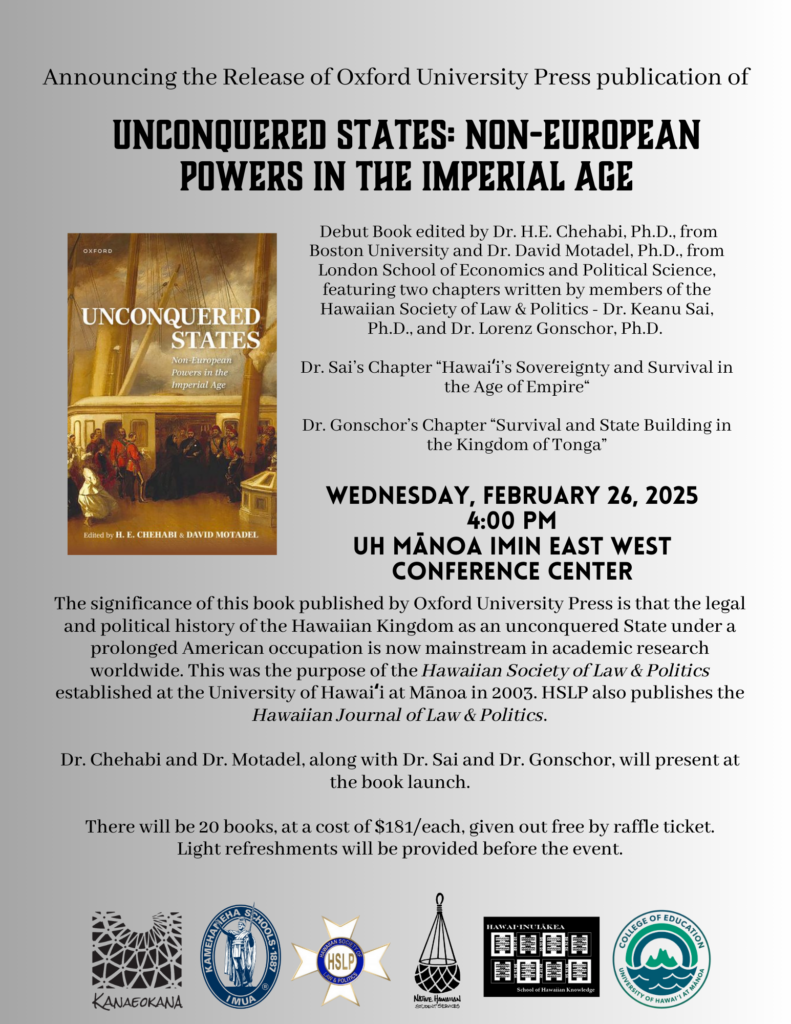

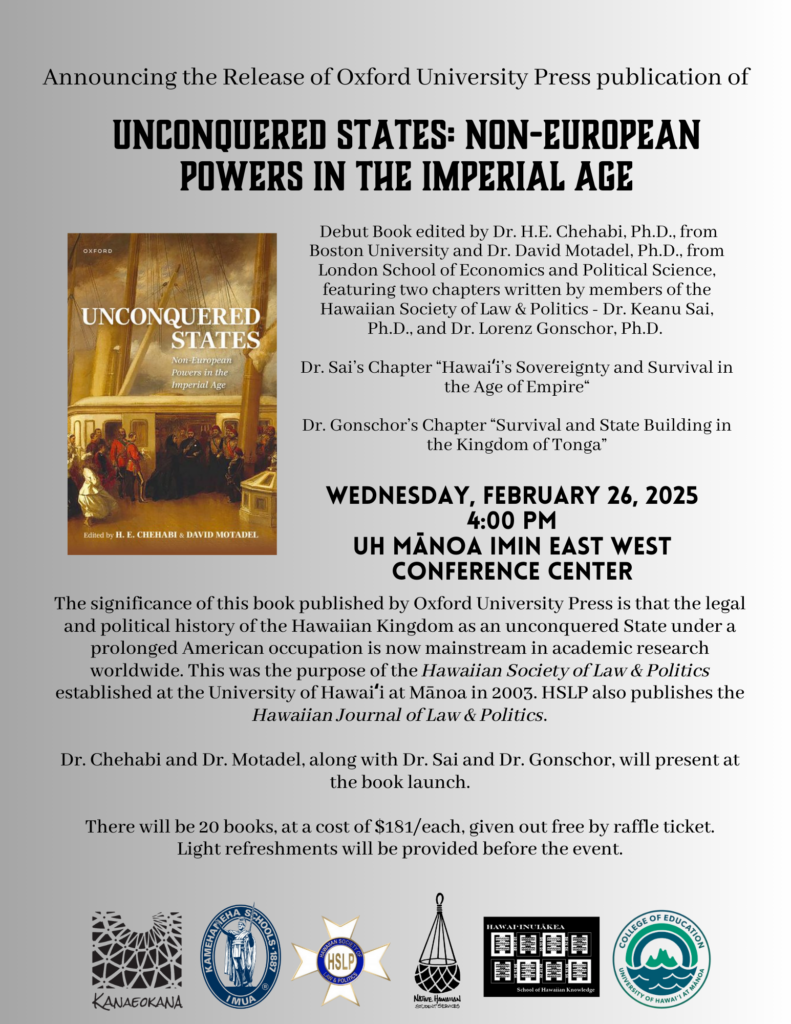

Book Launch Tomorrow at the University of Hawai‘i of Oxford University Press’ publication of “Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age” with a Chapter on the American Occupation of Hawai‘i

Tomorrow will be the official book launch of Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age published by England’s Oxford University Press in December of 2024. Dr. Keanu Sai is a contributor of a chapter in the book titled “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire.” In his chapter Dr. Sai

In his chapter, Dr. Sai covers: the legal and political history of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the evolution of governance as a constitutional monarchy, the unlawful overthrow of the government by United States troops in 1893, the prolonged American occupation since 1893, the restoration of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1997 by a Council of Regency, and the recognition of the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a State, and the Council of Regency, as its provisional government, by the Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Netherlands, in the 1999-2001 international arbitration case Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom. He concludes his chapter with:

Despite over a century of revisionist history, “the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign State is grounded in the very same principles that the United States and every other State have relied on for their own legal existence.” The Hawaiian Kingdom is a magnificent story of perseverance and continuity.

THE EVENT WILL BE LIVE STREAMED ON FACEBOOK STARTING AT 3:30pm HI TIME

KITV Island Life Live—Dr. Keanu Sai talks about his recent publication by Oxford University Press on the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom

On KITV Island Life Live yesterday, Dr. Keanu Sai talks about his recent chapter titled “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire” in a book Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age. The book was published by Oxford University Press in December of 2024. Be sure to download Dr. Sai’s chapter by clicking the link above.

KITV Island Life Live—Dr. Keanu Sai Explains the American Invasion and Illegal Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom Government on January 17, 1893

On KITV Island Life Live yesterday, Dr. Keanu Sai explains the American invasion of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its unlawful overthrow of the government on January 17, 1893. This began a prolonged occupation that is now at 132 years.

Pascal’s Substack—The Kingdom of Hawaii: Year 132 under U.S. Occupation

On January 4, 2025, Pascal Lottaz, a Professor for Neutrality Studies at the Waseda Institute for Advanced Study, (Waseda University), in Tokyo, posted a review of Dr. Keanu Sai’s chapter on Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire in Professor H.E. Chehabi and Professor David Motadel’s book Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age published by Oxford University Press.

ITS OFFICIAL: England’s Oxford University Press publication of “Unconquered States” makes the American Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom the Longest in Modern History

Oxford University Press (OUP) has made it official that the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom is the longest occupation in modern history that began in 1893. It was previously thought that the longest occupation in modern history was the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and East Jerusalem that began in 1967.

The significance of OUP’s publication of Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age, with a chapter written by Dr. Keanu Sai titled “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire” is that Hawai‘i was never the 50th State of the American Union but rather an occupied State under international law with its rights and obligations intact despite the prolonged nature of the occupation. What was defeated or overthrown, albeit illegally, was the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893, and not the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State, which is also referred to as the country.

Dr. Sai’s chapter reconnects the Hawaiian Kingdom to Great Britain, not the United States, when it became a British Protectorate in 1794 under the reign of King Kamehameha I. In 1843, Great Britain recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign and independent State, which ushered in the Hawaiian Kingdom into the Family of Nations. Dr. Sai then explains the connection to the United States by an invasion of U.S. Marines on January 16, 1893, which led to the unlawful overthrow of the Hawaiian government and its unlawful seizure of the Hawaiian Islands during the Spanish-American War in 1898. To be conquered is for the Hawaiian Kingdom to have transferred its sovereignty and territory to the United States by a treaty of cession.

There is no such treaty that exists except for the unlawful imposition of American laws, which is the war crime of usurpation of sovereignty during military occupation. Dr. Sai explains under international law why the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as an occupied State under international law, which the Permanent Court of Arbitration acknowledged in 1999, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom. The PCA not only acknowledged the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continuity as a State, but also recognized the Council of Regency as its provisional government during the occupation.

Dr. Sai was one of 23 academic scholars from around the world that was invited to write a chapter on a non-European State that was not conquered under international law. If Dr. Sai’s chapter had no historical or legal basis, OUP would not have allowed the chapter to be published. This is a cornerstone of academic research where a scholar does not argue a position in their research, but rather provides historical and legal evidence that cannot be refuted. In this sense, the scholar is subject to a scientific approach where a scholar’s findings and conclusions are open for rebuttal by other scholars who serve as reviewers. This is called peer review in the academic world where opinions have no place. OUP states in the book, “Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.”

Only when the American occupation is recognized worldwide can the occupation come to an end by a treaty of peace. OUP is added leverage to bring compliance to the law of occupation or the criminal culpability that ensues if the State of Hawai‘i is not transformed into a Military Government to administer the laws of the occupied Hawaiian Kingdom.