For the first time in its history, the United Nations General Assembly received a complaint from a Non-Member State of the United Nations. Today, August 14, 2025, the President of the UN General Assembly received the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Complaint of the United States of America’s unlawful and prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom since January 17, 1893, and the commission of war crimes and human rights violations pursuant to Article 35(2) of the UN Charter. It has been the practice of States to submit formal complaints with the UN Security Council but not with the General Assembly. This is a first ever complaint to be received by the General Assembly under to Article 35(2).

Article 35(2) provides: “A state which is not a Member of the United Nations may bring to the attention of the Security Council or of the General Assembly any dispute to which it is a party if it accepts in advance, for the purposes of the dispute, the obligations of pacific settlement provided in the present Charter.”

While the Hawaiian Kingdom is a State under international law, it is a Non-Member State of the UN. While Switzerland is a State and a Member of the UN, it did not join the UN until 2002. Like Switzerland prior to 2002, the Hawaiian Kingdom is a Non-Member State. Article 35(2) addresses situations that endanger international peace and security. The 132-year American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the commission of war crimes, and the refusal of the State of Hawai‘i to transform into a Military Government meet this criterion.

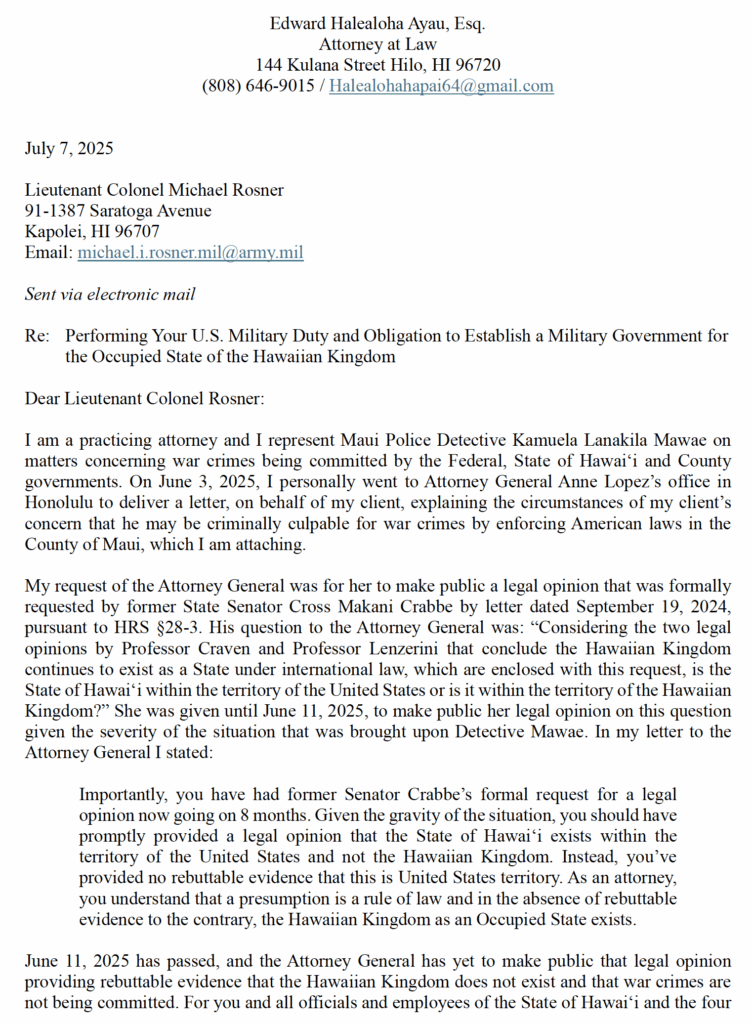

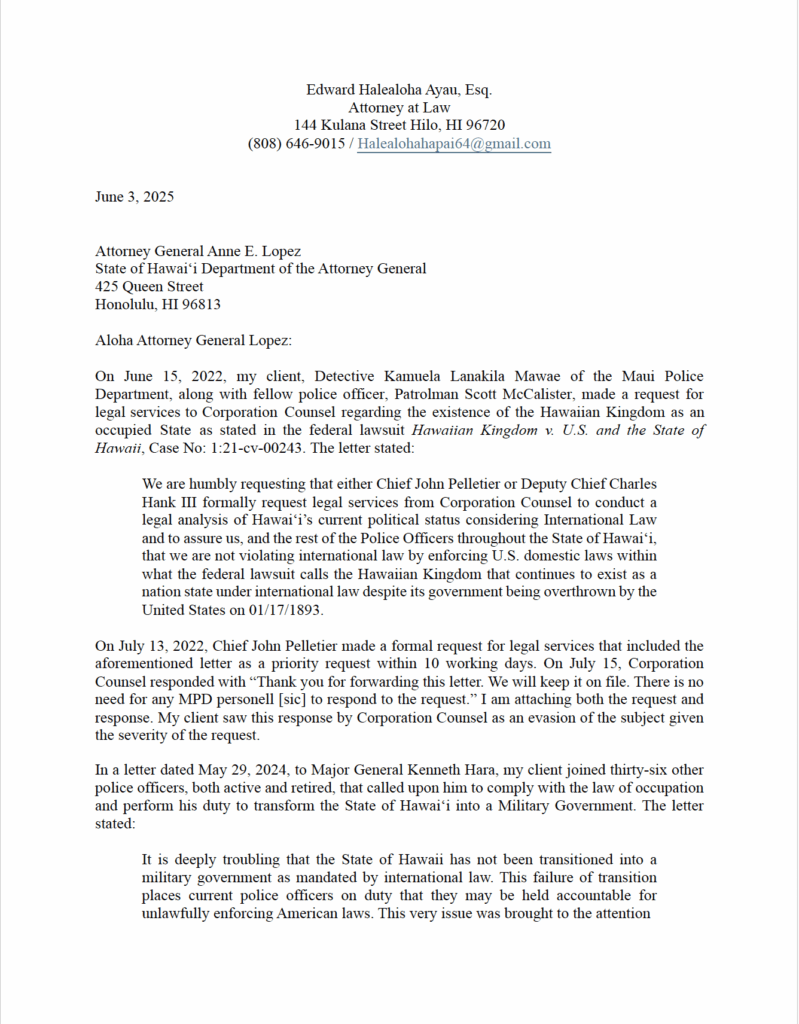

Before the President can apply the UN procedure for complaints submitted by a Non-Member State under Article 35(2), he would need to first determine the legal status of the Hawaiian Kingdom, according to international law, to be a State who is not a Member of the UN. In anticipation of this query, Dr. David Keanu Sai, Minister of Foreign Affairs ad interim, in his letter to His Excellency Philomon Yang, President of the UN General Assembly, that enclosed the Hawaiian Kingdom Complaint, stated:

In the Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (1999-2001), I served as Lead Agent for the Council of Regency representing the Hawaiian Kingdom. As such, I was in communication with the Permanent Court’s Principal Legal Counsel, Ms. Bette Shifman, whose responsibility was to determine whether the Hawaiian Kingdom exists as a State in continuity since the nineteenth century. This determination was necessary for the purpose of establishing the Permanent Court’s institutional jurisdiction in accordance with Article 47 of the 1907 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes. Article 47 provides, “The jurisdiction of the Permanent Court may, within the conditions laid down in the regulations, be extended to disputes between non-Contracting Powers or between Contracting Powers and non-Contracting Powers, if the parties are agreed on recourse to this Tribunal.” State continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom is determined by the rules of customary international law.

Prior to the Permanent Court’s establishment of the arbitral tribunal on 9 June 2000, the Secretariat determined that the Hawaiian Kingdom had met the standing of a State and was thus, recognized as a non-Contracting Power. This fact is noted in Annex 2—Cases Conducted under the Auspices of the PCA or with the Cooperation of the International Bureau in the Permanent Court’s Annual Reports from 2000 to 2011. The Permanent Court also recognized the Council of Regency as the Hawaiian Kingdom’s government. I am enclosing a copy of Annex 2 from the 2011 Annual Report. It identifies Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom as the thirty-third case that came under the auspices of the Permanent Court. Since 2012, the Annual Reports no longer include Annex 2 because the Permanent Court’s website provides the list of cases, which includes Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, Case no. 1999-01.

Under civilian law, the juridical fact, of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence as a State, produced the legal effect for the Secretariat to perform the juridical act of accepting the dispute, under the auspices of the Permanent Court, by virtue of Article 47. According to Professor Lenzerini, this juridical act “may be compared—mutatis mutandis—to a juridical act of a domestic judge recognizing a juridical fact (e.g. filiation) which is productive of certain legal effects arising from it according to law.” Since State members of the Permanent Court’s Administrative Council furnishes all Contracting States with an Annual Report, this represents “State practice [that] covers an act or statement by…State[s] from which views can be inferred about international law,” and it “can also include omissions and silence on the part of States.”

Since the United States and all Contracting States did not object to the Secretariat’s juridical act of acknowledging the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence as a non-Contracting State, this reflects the practice of States—opinio juris. Furthermore, the Secretariat and the Administrative Council are treaty-based components of an intergovernmental organization comprised of representatives of States, and, therefore, “their practice is best regarded as the practice of States.” According to Professor Lenzerini, “it may be convincingly held that the PCA contracting parties actually agreed with the recognition of the juridical fact of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State carried out by the International Bureau.”

Of the one hundred ninety-three Member States of the United Nations, one hundred twenty-three of these States are also Member States of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, to wit:

Albania, Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Austria, The Bahamas, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belgium, Belize, Benin, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, Canada, Chile, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cuba, Cyprus, Czechia, the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe, Denmark, Djibouti, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Eritrea, Estonia, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Fiji, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Hungary, Iceland, India, Iran, Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Latvia, Lebanon, Libya, Lithuania, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Madagascar, Malaysia, Malta, Mauritius, Mexico, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Nigeria, North Macedonia, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, the People’s Republic of China, Peru, Philippines, the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Romania, Republic of Korea, Russian Federation, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Serbia, Singapore, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Suriname, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Togo, Türkiye, Uganda, Ukraine, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, United States of America, Uruguay, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Viet Nam, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. And Palestine, who is an Observer State, is also a Member State of the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

Hence, these States already recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State and the Council of Regency as its Government by virtue of their membership, as Contracting States, of the Permanent Court of Arbitration. Of note Your Excellency, is that your country—Cameroon is not only a Successor State to the 1851 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation between the Hawaiian Kingdom and Great Britain but also recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom and its Council of Regency as a Member State of the Permanent Court.

Minister Sai also brought to the attention of President Yang the identification of 154 Member States of the UN that currently have treaties with the Hawaiian Kingdom by virtue of international law. Minister Sai states:

The successor States of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s treaty partners, were not aware at the time of their independence, that the Hawaiian Kingdom continued to exist as a State, therefore, neither the newly independent States nor the Hawaiian Kingdom could declare “within a reasonable time after the attaining of independence, that the treaty is regarded as no longer in force between them.” Until there is a clarification of the successor States’ intentions, as to a common understanding with the Hawaiian Kingdom regarding the continuance in force of the Hawaiian treaty with their predecessor States, the Hawaiian Kingdom will presume the continuance in force of its treaties with the successor States. The majority of Member States of the United Nations are successor States to treaties with the Hawaiian Kingdom.

This position, taken by the Hawaiian Kingdom, is consistent with the 1978 Vienna Convention on Succession of States in respect of Treaties. Article 24 states:

1. A bilateral treaty which at the date of the succession of States was in force in respect of the territory to which the succession of States relates is considered as being in force between a newly independent State and the other State party when:

a. they expressly so agree; or

b. by reason of their conduct they are to be considered as having agreed.

2. A treaty considered as being in force under paragraph 1 applies in the relations between the newly independent State and the other State party from the date of the succession of States, unless a different intention appears from their agreement or is otherwise established.

Since successor States, which include Member States of the United Nations, were unaware of the existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom at the time of their independence, and its treaties with their predecessor States, Article 24(1)(a) and (b) could not arise. Therefore, under customary international law, in the absence of an express agreement or an agreement by conduct, the Hawaiian Kingdom will presume that its treaties continue in force, for two years from the receipt of this communication, with the successor States. Here follows the list of successor States to Hawaiian Kingdom treaties:

• 1875 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the Austro-Hungarian Empire—Austria and Hungary.

• 1862 Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation between the Hawaiian Kingdom and Belgium—Burundi, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Rwanda.

• 1857 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation between the Hawaiian Kingdom and France—Algeria, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Gabon, Guinea, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Lebanon, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Senegal, Syrian Arab Republic, Togo, Tunisia, Vanuatu, and Viet Nam.

• 1851 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation between the Hawaiian Kingdom and Great Britain—Afghanistan, Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, The Bahamas, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belize, Bhutan, Botswana, Brunei Darussalam, Cameroon, Canada, Cyprus, Egypt, Eswatini, Fiji, Gambia, Ghana, Grenada, Guyana, India, Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Jamaica, Jordan, Kenya, Kiribati, Kuwait, Lesotho, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Malta, Mauritius, Myanmar, Namibia, Nauru, Nepal, New Zealand, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Qatar, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tonga, Trinidad and Tobago, Tuvalu, Uganda, United Arab Emirates, United Republic of Tanzania, Vanuatu, Yemen, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

• 1863 Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation between the Hawaiian Kingdom and Italy—Libya and Somalia.

• 1871 Treaty of Amity and Commerce between the Hawaiian Kingdom and Japan—Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the Republic of Korea.

• 1862 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the Netherlands—Indonesia and Suriname.

• 1882 Treaty between the Hawaiian Kingdom and Portugal—Angola, Cabo Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Sao Tome and Principe, and Timor-Leste.

• 1869 Treaty of Commerce and Navigation between the Hawaiian Kingdom and Russia—Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Mongolia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Republic of Moldova, Slovenia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

• 1863 Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the Hawaiian Kingdom and Spain—Cuba and Equatorial Guinea.

• 1852 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway—Norway and Sweden.

• 1849 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States—Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Palau, Philippines.

The Hawaiian Kingdom has treaties with one hundred fifty-four Member States of the United Nations, of which fourteen treaties are with the original States, and one hundred forty treaties are with the successor States.

According to the UN complaint procedure, when the President of the General Assembly receives a formal complaint by a State, whether a Member of the UN or not, he will assess the complaint based on the rules of procedure and the established practices of the General Assembly. Because there is no practice to follow by the President, given this is the first time a complaint has been submitted to the General Assembly by a State under Article 35(2), he will have to be guided by what the Hawaiian Kingdom is seeking in its complaint.

The Hawaiian Kingdom is not seeking to resolve a dispute but is rather bringing to the attention of the General Assembly the situation in the Hawaiian Kingdom so that it can take certain actions to address the situation of an unlawful and prolonged occupation of a State under international law. What the Hawaiian Kingdom requests of the General Assembly is clearly stated in paragraph 2.3 of the Complaint.

The Hawaiian Kingdom herein files this Complaint as a Non-Member State, pursuant to Article 35(2) of the United Nations Charter, for the violation of treaties and international law and calls upon the United Nations General Assembly:

1. To ensure the United States of America complies with international humanitarian law and the law of occupation;

2. To ensure that the United States of America establishes a military government, by its State of Hawai‘i, to administer the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom as it stood before the American invasion and unlawful seizure of the Hawaiian Government on 17 January 1893, and the provisional laws, proclaimed by the Council of Regency on 10 October 2014, that bring Hawaiian Kingdom laws to the current state; and

3. To ensure that all Member States of the United Nations shall not recognize as lawful the United States of America’s presence and authority within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom, except for its temporary and limited authority vested under the law of occupation.

The Hawaiian Kingdom’s third request does not require collective action to be taken by the General Assembly. The individual Member States of the General Assembly would be obligated to take individual action themselves regarding the Hawaiian situation once they have been made aware of the Hawaiian situation by the Complaint.

Under Article 41(2) of the UN Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts committed by the United States against the Hawaiian Kingdom, “No State shall recognize as lawful a situation created by a serious breach within the meaning of article 40, nor render aid or assistance in maintaining that situation.” Article 40 provides, “This chapter applies to the international responsibility which is entailed by a serious breach by a State of an obligation arising under a peremptory norm of general international law.”

Since the prolonged occupation and the commission of war crimes is a serious breach of peremptory norms of general international law, Article 41(2) is triggered once a State is made aware of the Hawaiian situation by the Complaint. As such, States are obligated to take individual action on the Hawaiian Kingdom’s third request to “not recognize as lawful the United States of America’s presence and authority within the territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom, except for its temporary and limited authority vested under the law of occupation.” A General Assembly resolution is not required for a State to immediately act.

According to Minister Sai, “The contents of my letter to President Yang and the information provided in the complaint reflects the tedious work of the Council of Regency in carrying out its strategic plan to address the prolonged occupation of the country. The State of Hawai‘i now finds itself at a cross road to begin to comply with the law of occupation by establishing a Military Government according to the Council of Regency’s Operational Plan or face prosecution for war crimes. The State of Hawai‘i’s deliberate failure has not only provided the evidential basis for submitting the complaint as a Non-Member State of the United Nations, but to bring international attention to our situation.”

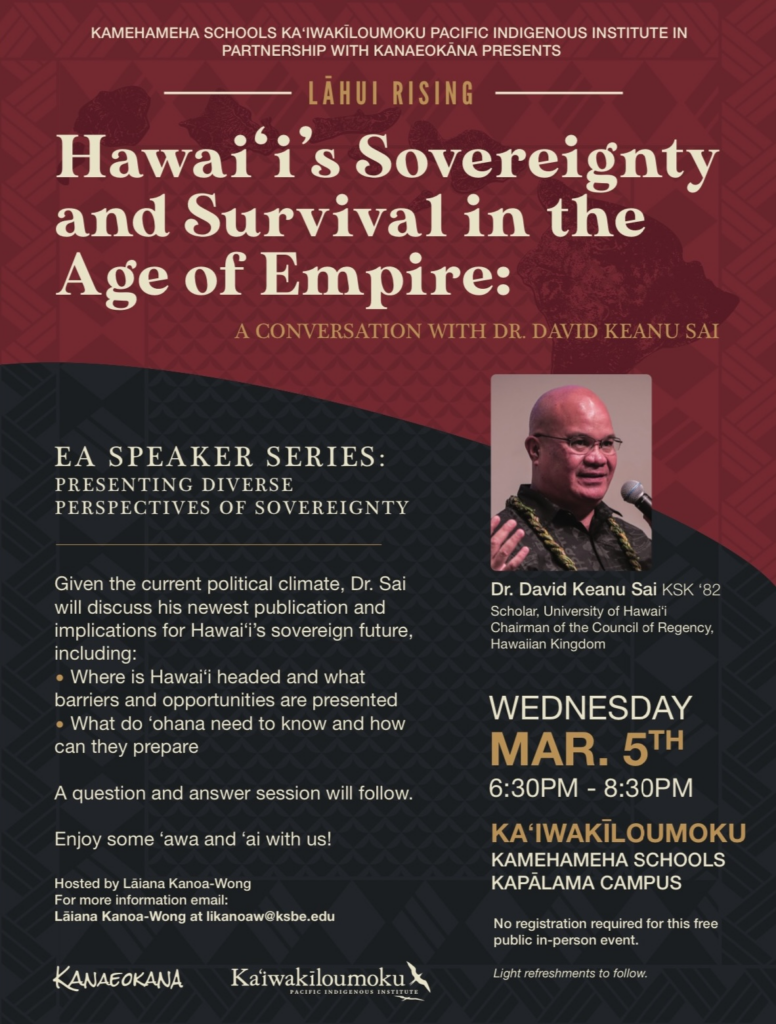

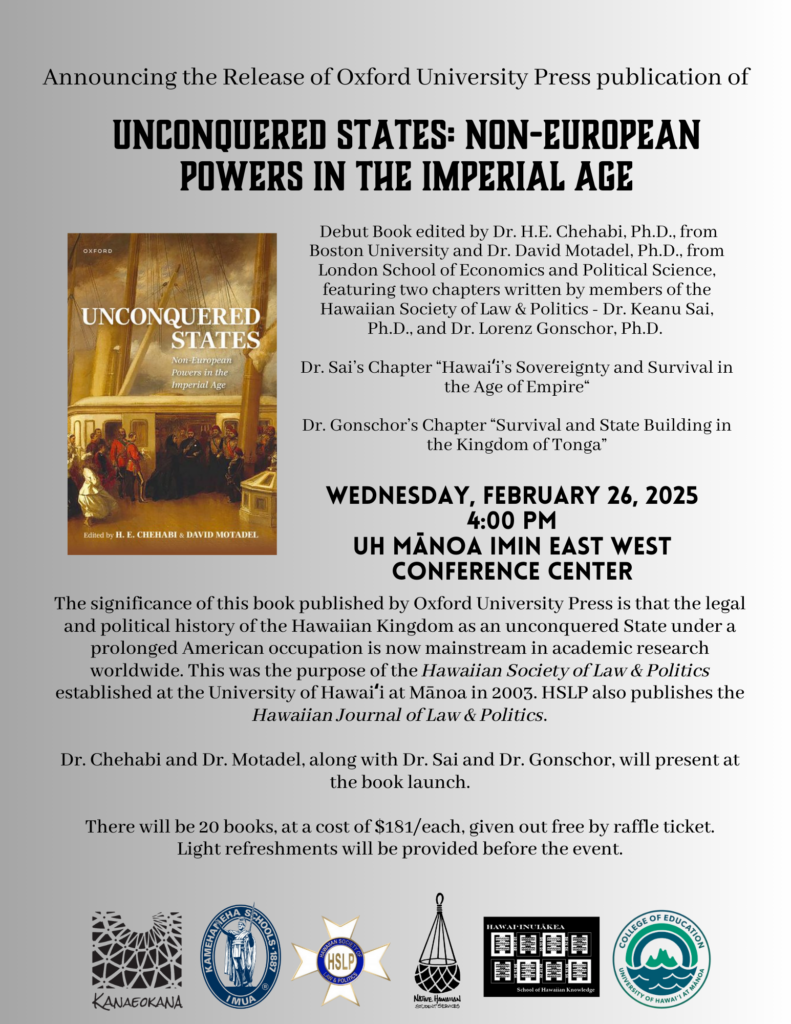

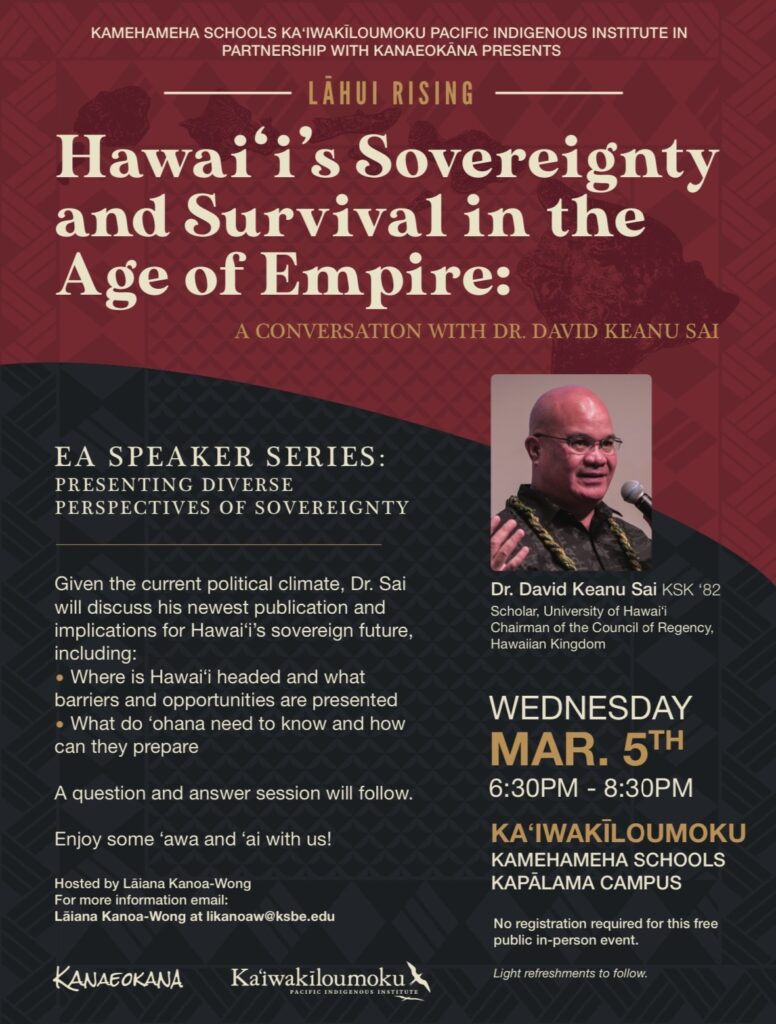

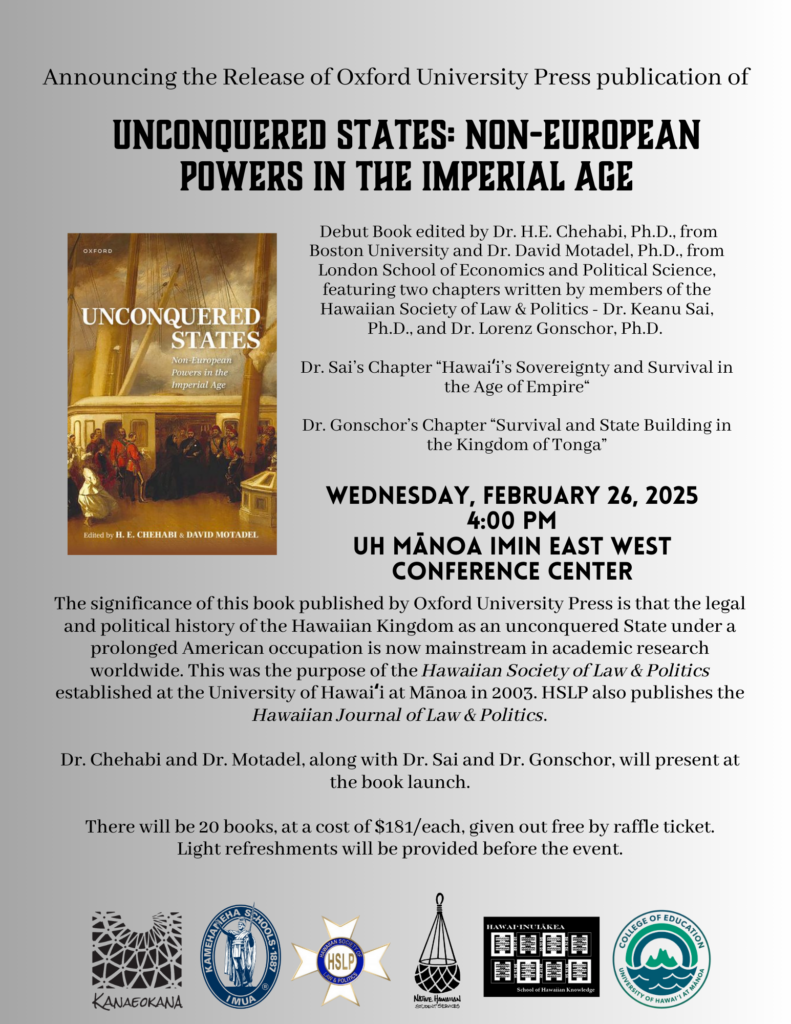

Minister Sai also stated, “Oxford University Press’ recent publication of my chapter “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire,” in the 2024 book Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age, has opened many doors for the Council of Regency that were not opened before. As the entire world is watching our history in Chief of War on Apple TV, they will now know our true history that followed those epic battles of Kamehameha I when we became a British Protectorate in 1794, Kamehameha’s consolidation of the island kingdoms into the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1810, transforming into a constitutional monarchy in 1840, becoming a sovereign and independent State in 1843, and its continued existence as a State under international law despite the prolonged American occupation since our country was invaded by U.S. Marines in 1893. To use the idiom for the filing of the UN Complaint, ‘We must strike when the iron is hot!'”