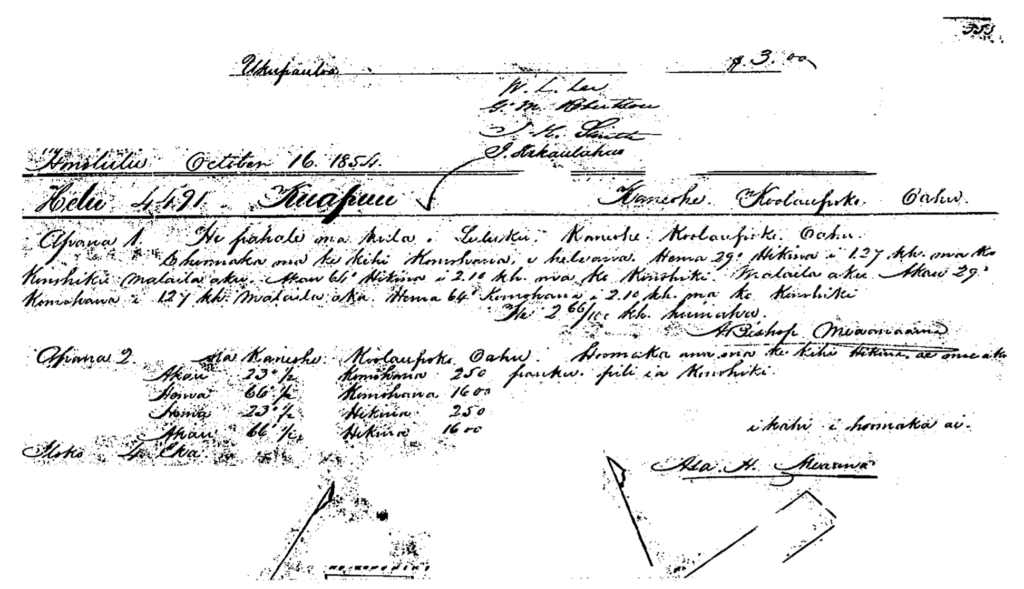

There is much confusion on the 1848 Great Māhele that stems from the Hawaiian Indigeneity movement made up of scholars at the universities. This prompted Dr. Keanu Sai to write an article titled “Setting the Record Straight on Hawaiian Indigeneity” in 2021 that was published in volume 3 of the Hawaiian Journal of Law and Politics. Dr. Sai covers the false narrative of the Māhele that was promoted by the Hawaiian Indigeneity movement. The Māhele, as a process, is explained under the heading of Land Reform on page 67 in the eBook published by the Royal Commission of Inquiry. And the Royal Commission of Inquiry published its Preliminary Report on the Legal Status of Land Titles throughout the Real in 2020.

The Hawaiian Indigeneity movement manufactured the false belief that the Hawaiian Kingdom was controlled by Americans. In his book Dismembering Lahui: A History of the Hawaiian Nation to 1887, Professor Jon Osorio wrote that the Hawaiian Kingdom “never empowered the Natives to materially improve their lives, to protect or extend their cultural values, nor even, in the end, to protect that government,” because the system itself was foreign and not Hawaiian. Professor Sally Merry stated, in her book Colonizing Hawai‘i: The Cultural Power of Law, “the relationship between Euro-Americans and Native Hawaiians was a classical colonial relationship [that sought] to transform the society of the indigenous people and subsequently wrested political control from them.” Dr. Robert Stauffer wrote, in his book Kahana: How the Land was Lost, “the government that was overthrown in 1893 had, for much of its fifty-year history, been little more than a de facto unincorporated territory of the United States…[and] the kingdomʻs government was often American-dominated if not American-run.” And in her book Aloha Betrayed: Native Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism, Professor Noenoe Silva wrote that the overthrow “was the culmination of seventy years of U.S. missionary presence.” These conclusions have no basis in historical facts and relevant laws.

Another false narrative driven by the Hawaiian Indigeneity movement is that all Native Hawaiians are called Kanaka Maoli. In Hawaiian law, kanaka maoli refers to aboriginal Hawaiians that are pure blood, and those that are part aboriginal Hawaiian are hapa. According to Pukui and Elbert’s Hawaiian Dictionary, kanaka maoli are “Full-blooded Hawaiian persons.” This is also reflected in Bernice Pauahi’s will that established the Kamehameha Schools. Article 13 states, “I direct my trustees to devote a portion of each years income to the support and education of orphans, and others in indigent circumstances, giving the preference to Hawaiians of pure or part aboriginal blood.” Hawaiian is short for Hawaiian subject, which is the nationality, while aboriginal Hawaiian whether full or part is the race. If you are not a full-blooded aboriginal Hawaiian, you are not kanaka maoli but rather hapa.

The cornerstone of the Hawaiian Indigeneity movement is how terrible the 1848 Great Mahele was for the commoner or native tenant. In her book Native Land and Foreign Desires, Professor Lilikala Kame‘eleihiwa wrote, “The culmination of changes in traditional Land tenure in Hawai‘i in 1848 is commonly known as the ‘Great Māhele.’ I refer to it simply as the ‘1848 Māhele’ because it proved to be such a terrible disaster for the Hawaiian people, and the word ‘great’ has a connotation of superior. It was a tragic historical event, a turning point that had catastrophic negative consequences for Hawaiians.”

In his book, Dismembering Lahui, Professor Osorio agrees with Professor Kame‘eleihiwaʻs conclusion by writing, “As significant an event as the Māhele has proven to be, historians have seen it as a way of making specific indictments either of Ali‘i or of colonialism. No one disagrees that the privatization of lands proved to be disastrous for Maka‘ainana [commoners], yet the focus of every study, from John Chinen’s 1958 work to Kame‘eleihiwa in 1992, has been to try and establish the principal responsibility for its ‘failure.’”

Professor Kame‘eleihiwa wrongly claimed that the native tenants that submitted their claims with the Board of Commissioners to Quiet Land Titles, also known as the Land Commission, were the only native tenants that got land through the Māhele. She stated that the commoner class only received “a total of 28,658 acres of Land, which is less than 1 percent of the total acreage of Hawai‘i.” These native tenants were able to acquire fee-simple titles to their land under the 1850 Act Confirming Certain Resolutions of the King in Privy Council, passed on the 21st day of December, A.D. 1849, Granting to the Common People Allodial titles for their own Lands and House lots, and certain other Privileges. This law came to be known as the Kuleana Act.

The Kuleana Act addressed those native tenants that were not able to file their claim with Land Commission before the due date of February 14, 1848, by empowering them to go to the Minister of the Interior or his special agents to acquire up to fifty acres of land. The Minister of the Interior was responsible for the administration of Government lands that it received through the Mahele on June 7, 1848. In 1882, the Surveyor General reported to the Legislative Assembly that between “the years 1850 and 1860, nearly all the desirable Government land was sold, generally to natives.”

Donovan Preza, in his M.A. thesis on the Great Māhele tallied the number of acreage acquired by native tenants within this ten year period to be a remarkable 111,448.36 acres. This number of acreage is in addition to the 28,658 acres that commoners acquired from the Land Commission that Kame‘eleihiwa and Osorio hang theirs hats on as their sole evidence of oppression. By 1893, native tenants acquired from the Government a total of 167,290.45 acres. This is not evidence of dispossession and oppression of the commoners by the aristocracy and missionaries as argued by the movement of Hawaiian Indigeneity.

In a podcast interview on November 28, 2020, Professor Osorio made a startling comment. He said that the Māhele was “done to protect the hoaʻāina, the makaʻāinana, the people of the land who are not chiefs; to protect their existence on the land, and this is one of the most amazing things about the Māhele, and it was something that I didn’t really understand when I wrote my book. It was something that, really…Professor Keanu Sai makes clear to all of us.”

Professor Kame‘eleihiwa mistakenly thought that the Māhele was a singular event and not a process for separating the rights of the Government, Konohikis and the native tenants. The rights of these three entities were undivided. In the Hawaiian language, mahele is to divide and mahele‘ole is undivided. The 1839 Declaration of Rights established three vested rights in all the lands of the Hawaiian Kingdom. As the 1840 Constitution explains:

Kamehameha I, was the founder of the kingdom, and to him belonged all the land from one end of the Islands to the other, though it was not his own private property. I belonged to the chiefs and people in common, of whom Kamehameha I was the head, and had the management of the landed property.

The land tenure system was feudal. In 1882, the Surveyor General reported to the Legislative Assembly, “The ancient system of land titles in the Hawaiian Islands was entirely different from that of tribal ownership prevailing in New Zealand, and from the village or communal system of Samoa, but bore a remarkable resemblance to the feudal system that prevailed in Europe during the Middle Ages.”

As part of their vassalage, the chiefs had to pay the King taxes from their plantations, which was in swine, and the native tenants had to provide labor tax for both King and their chiefs on their plantation lands. The chiefs had to pay a particular weight of the swine per plantation or its equivalent in cash. The chiefs were also referred to as landlords. According to the Laws of 1842 Laws of the Hawaiian Islands that accompanied the 1840 Constitution, it stated:

The following is the rate of taxation for plantations, and, farms including plantations. There shall be no state, country, town and district tax, but only the following:

A large farm—a swine one fathom long.

A smaller one—a swine three cubits long.

A very small one—a swine one yard long.

If not a fathom swine, then 10 dollars.

If not a three cubit swine, then 7 ½ dollars.

If not a yard swine, then 5 dollars.

For the native tenants, the 1842 laws stated:

Hereafter a tax in labor shall not be required on every week of the month.—On two weeks, labor shall be done for his Majesty the King and also the landlords, and two weeks the people shall have wholly to themselves. The first week in the month the people shall work two days for the king and one for the landlords; the second week in the month they shall work one day for his Majesty the King, and two days for the landlords, and the next two weeks the people shall have to themselves.

Foreigners who were granted lands by the King and the chiefs were not part of the feudal system so they did not do any labor tax. On December 10, 1845, the Legislature began land reform by enacting a law establishing the Land Commission. The mandate of the Land Commission was to investigate all claims to private property that existed outside of the feudal system. Claimants to these lands had to file their claims for investigation between February 14, 1846, and February 14, 1848. Those that were required to file their claims to land were those who acquired their lands from the King or a chief prior to December 10, 1845.

After the investigation, the Land Commission would grant a Land Commission Award with a number if the claim was found valid. If it was rejected there was no Land Commission Award. Foreigners and those chiefs or native tenants that possessed property outside of the feudal system were required to file their claims. If they did not get their claim in before February 14, 1848, the lands reverted to the King and Government.

According to the Principles of the Land Commission:

The following benefits will result from these investigations and awards:—

1st. They will separate the rights of the King and Government, hitherto blended, and leave the owner, whether in fee, or for life, or for years, to the free agency and independent proprietorship of his lands as confirmed. So long as the King or Government continue to have an undivided proprietary share in the domain the King’s and Premier’s consent is necessary, by the old law, to real sales, or tranfers from party to party, and, by parity of reasoning, to real mortgages also. This is because of the share which Government or the body politic has in the lands of the kingdom uniformly. To separate these rights, and disembarrass the owner or temporary possessor from this clog upon his free agency, is beneficial to that proprietor in the highest degree, and also to the body politic; for it not only sets apart definitely what belongs to the claimant, but untying his hands, enables him to use his property more freely, by mortgaging it for commercial objects, and by building upon it, with the definite prospect that it will descend to his heirs. This will tend more rapidly to an export, and to a permanency of commercial relations, without which, there can never be such a revenue as to enable the Government to foster its internal improvements.

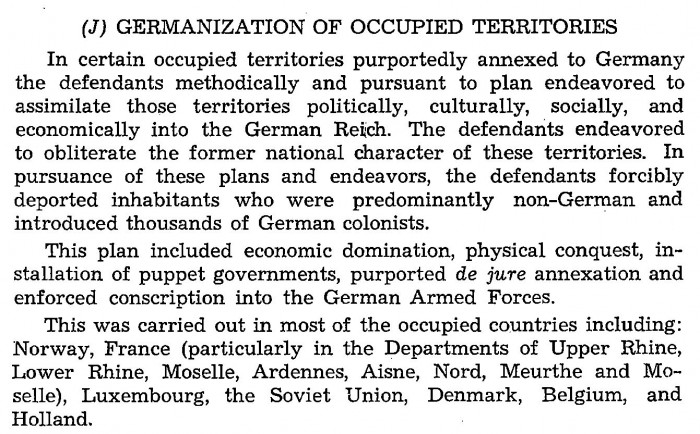

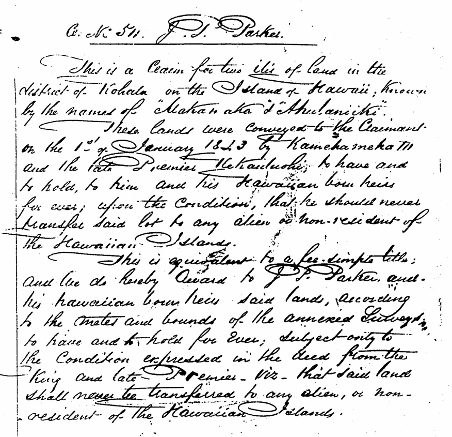

At this stage, the Land Commission was not authorized by law to grant titles to property but only to investigate and where found to be a valid claim issue a Land Commission Award. These Land Commission Awards vary from fee-simple, life estates, to leasehold. Below is Land Commission Award no. 511 issued to J.P. Parker. The Land Commission verified that Kamehameha III and the Premier Kekāuluohi conveyed a conditional fee-simple title to Parker on January 1, 1843.

On December 11, 1847, King Kamehameha III and his chiefs in Privy Council began to discuss the process of separating the rights of the Government from the chiefs, who were also called Konohikis, that would eventually lead to separating the rights of the Government and the Konohikis from native tenants. The purpose was to bring to an end the feudal system whereby the Konohiki and the native tenant will have an allodial title to their lands. According to Blackʻs Law Dictionary, allodial is “Free; not holden of any lord or superior; owned without obligation of vassalage or fealty; the opposite of feudal.” Fee-simple is synonymous with allodial.

There were 254 Konohikis and King Kamehameha III considered himself the highest of all Konohikis. He was making the separation of himself as a Konohiki under the feudal system and as Head of the Government. In the Privy Council minutes it states:

The King now claims to Konohiki of a great portion of the lands. He therefore makes known to the other Konohikis, that they are only holders of Lands under him, but he will only take a part and leave them a part…subject only to the rights of the Tenants.

The Chiefs do not greatly object to this, but they ask. Has the Government a third interest in the lands left to us? The King replies Yes and the Government has 1/3 interest in his. There are some who say no. Let us have an Allodial Title to what the King has left us subject only to the rights of the Tenants.

The Māhele formally began on January 17, 1848, where the King and Konohikis signed in a book the separation of the lands between themselves. This gave them a life estate to the lands assigned to them in the Māhele book called ahupua‘a and ‘ili kūpono. If they wanted to acquire the fee-simple interest in these lands they had to give the Government certain lands they received in the Māhele that would satisfy the one-third interest of the Government. Kamehameha III was the first Konohiki to do this when the Government, acting through its Legislature, accepted certain lands to be Government lands and the remaining lands became the fee-simple ownership of Kamehameha III. Kamehameha III’s lands came to known as Crown Lands that descended to the successors of the throne. According to the 1848 Act Relating to the Lands of His Majesty the King and of the Government:

[Listing of the ahupua‘a and ‘ili]

To be the private lands of His Majesty Kamehameha III, to have and to hold to himself, his heirs, and successors, forever; and said lands shall be regulated and disposed of according to his royal will and pleasure subject only to the rights of tenants.

[Listing of the ahupua‘a and ‘ili]

Made over to the Chiefs and People, by our Sovereign Lord the King, and we do hereby declare those lands to be set apart as the lands of the Hawaiian Government, subject always to the rights of tenants.

During the Māhele process amongst the Konohikis, native tenants were encouraged to file their claim with the Land Commission before the due date of February 14, 1848. Many native tenants did not make it in time. This is where the confusion lies regarding the Māhele. What is important to remember, the Land Commission was not authorized to grant titles to those who filed their claim, but rather only to investigate the claims to land. Native tenants that filed their claims with the Land Commission did not divide their rights yet with the Government or the Konohikis so they could not claim to have a fee-simple title to their lands. This will change the following year.

On December 21, 1849, the King in Privy Council passed resolutions so that the common people can get allodial or fee-simple titles to their lands, and to empower the Land Commission to grant these titles on behalf of the King and Konohikis. This would facilitate the process of separating the rights of the Government and the Konohikis from those claims that were filed with the Land Commission by native tenants. Although the resolution empowered the Land Commission to grant titles to native tenants, the Legislature was needed to amend the law that would allow the Land Commission to grant titles.

On August 6, 1850, the Legislature enacted an Act Confirming Certain Resolutions of the King and Privy Council, passed on the 21st day of December, A.D. 1849, Granting to the Common People Allodial titles for their Own Lands and House Lots, and Certain other Privileges. This law came to known as the Kuleana Act. The Kuleana Act stated:

Be it enacted by the House of Nobles and Representatives of the Hawaiian Islands, in Legislative council assembled:

That the following sections which were passed by the King, in privy council on the 21st of December, A.D. 1849, when the legislature was not in session, be and are hereby confirmed; and that certain other provisions be inserted, as follows:

- That fee-simple titles, free of commutation, be and are hereby granted to all native tenants, who occupy and improve any portion of any government land, for the lands they so occupy and improve, and whose claims to said lands shall be recognized as genuine by the land commission: Provided, however, that this resolution shall not extend to konohikis or other persons having the care of government lands, or to the house lots and other lands in which the government have an interest in the districts of Honolulu, Lahaina and Hilo.

- By and with the consent of the King and chiefs in privy council assembled, it is hereby resolved, that fee-simple titles free of commutation, be and are hereby granted to all native tenants who occupy and improve any lands other than those mentioned in the preceding resolution, held by the King or any chief or konohiki for the land they so occupy and improve; Provided, however, that this resolution shall not extend to house lots or other lands situated in the districts of Honolulu, Lahaina and Hilo

- That the board of commissioner to quiet land titles be, and is hereby empowered to award fee-simple titles in accordance with the foregoing resolutions; to define and separate the portions of lands belonging to different individuals; and to provide for an equitable exchange of such different portions, where it can be done, so that each man’s land may be by itself.

- That a certain portion of the government lands in each island shall be set apart, and placed in the hands of special agents, to be disposed of in lots from one to fifty acres, in fee-simple, to such natives as may not be otherwise furnished with sufficient land, at minimum price of fifty cents per acre.

- In granting to the people, their house lots in fee-simple, such as are separate and distinct from their cultivated lands, the amount of land in each of said house lots shall not exceed one quarter of an acre.

- In granting to the people their cultivated grounds, or kalo lands, they shall only be entitled to what they have really cultivated, and which lie in the form of cultivated lands; and not such as the people may have cultivated in different spots, with the seeming intention of enlarging their lots; nor shall they be entitled to the waste lands.

- When the landlords have taken allodial titles to their lands, the people on each of their lands, shall not be deprived of the right to take firewood, house timber, aho cord, thatch, or ti leaf, from the land on which they live, for their own private use, should they need them, but they shall not have a right to take such articles to sell for profit. They shall also inform the landlord or his agent, and proceed with his consent. The people shall also have a right to drinking water, and running water, and the right of way. The springs of water, and running water, and roads shall be free to all, should they need them, on all lands granted in fee-simple: Provided, that this shall not be applicable to wells and water courses which individuals have made for their own use.

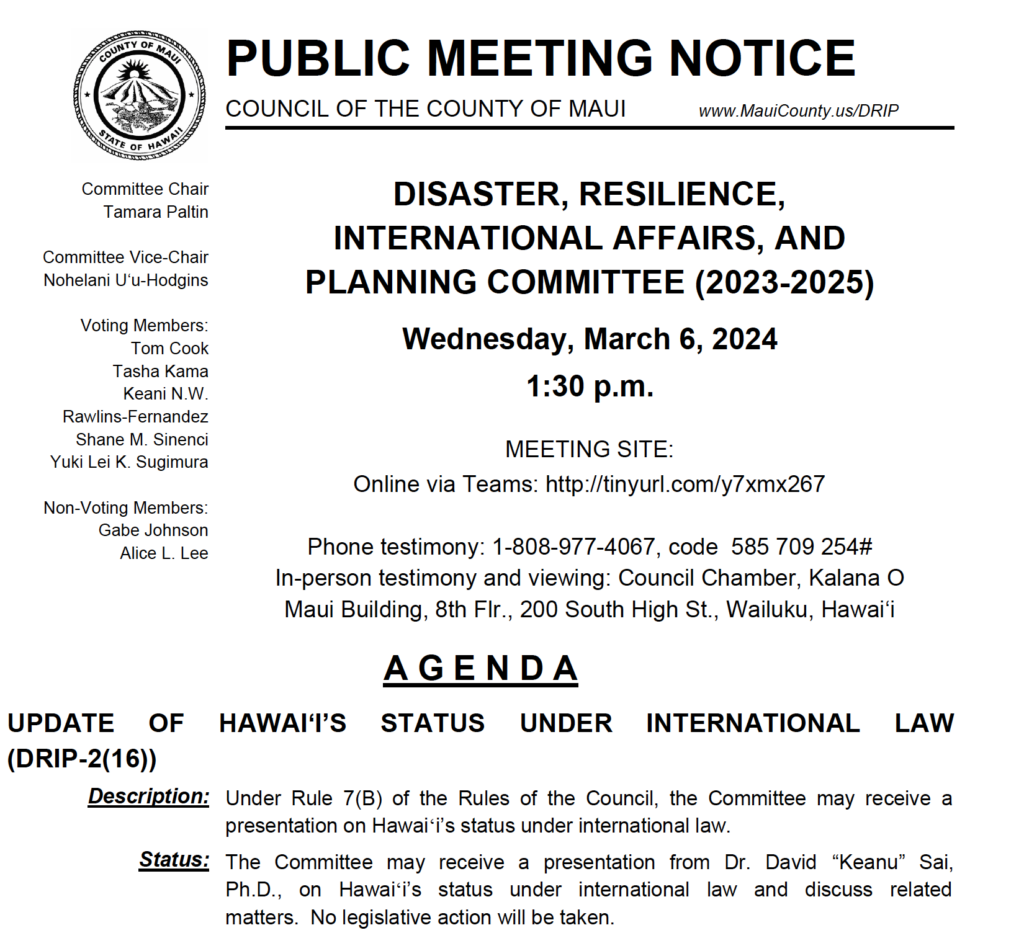

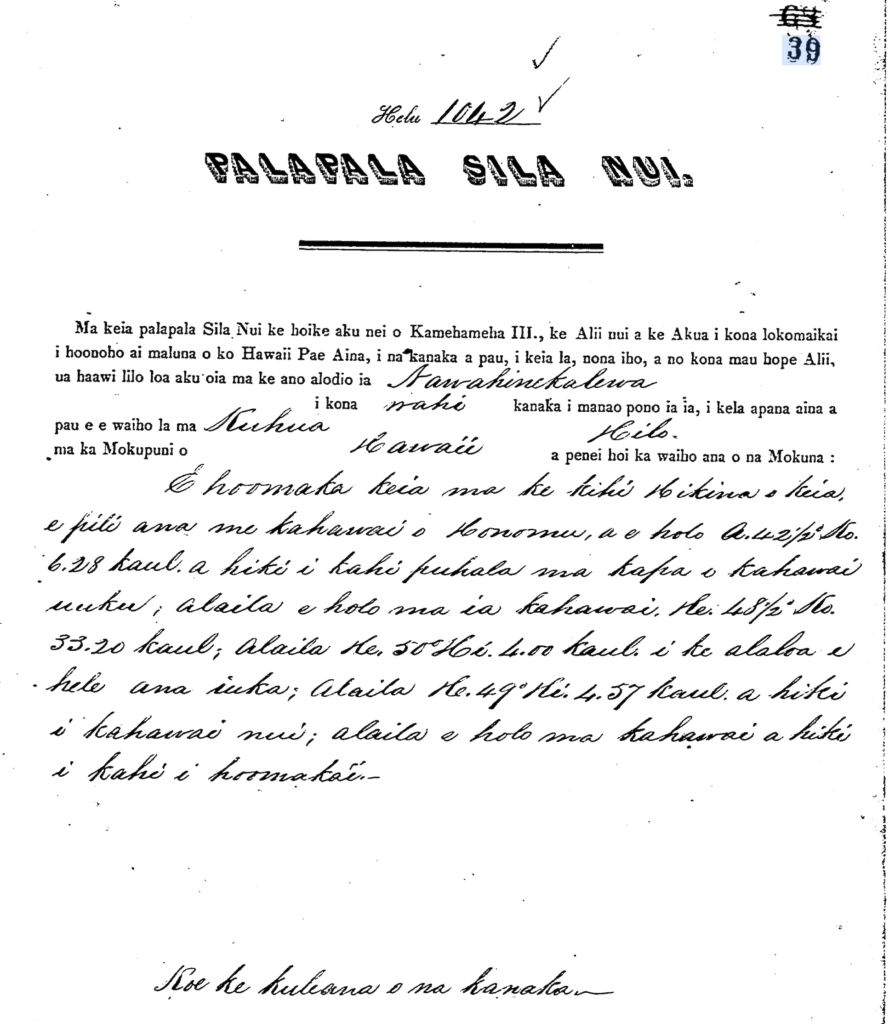

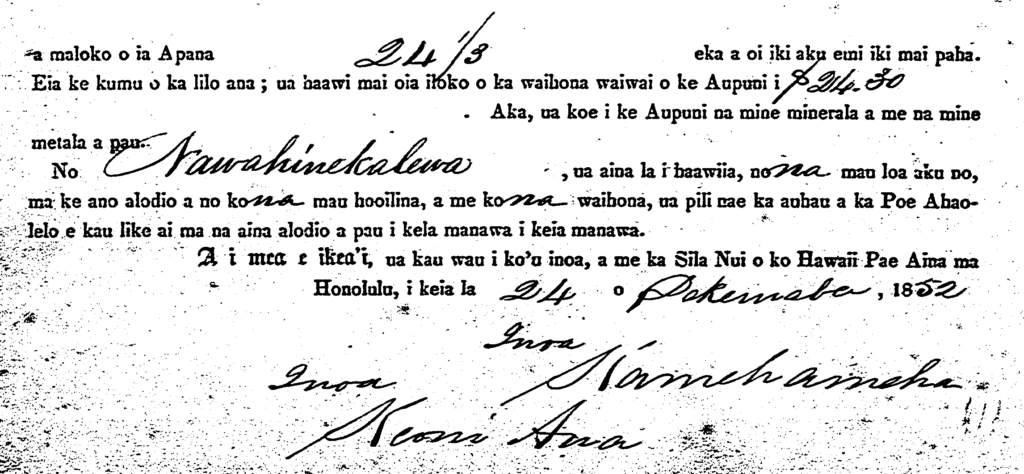

Sections 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7 applied to those native tenants that filed their claim with the Land Commission. While sections 4 and 7 applied to those native tenants that were not able to file their claim with the Land Commission but would go to the Minister of the Interior or special agents appointed by him to separate their interest with the Government. This group of native tenants did not get Land Commission Awards, but rather Royal Patent Grants. Below is Land Commission Award no. 4491 to Kuapu‘u by virtue of the Kuleana Act, followed by Royal Patent Grant no. 1042 to Kawahinekalewa by virtue of the Kuleana Act.

Of the three vested rights in the land, the Māhele was able to separate the Government from the 254 Konohiki lands, which included the Crown lands, and native tenants throughout the nineteenth century, whether by a Land Commission Award or a Royal Patent Grant. The Kuleana Act has not been repealed and still exists today for native tenants to acquire up to fifty acres in fee-simple. This is why the Māhele is a continuing process and not a singular event.

The Māhele was such a monumental event of moving Hawaiian land tenure from feudal to private ownership that it became known as the Great Māhele. On December 18, 1848, the King and Privy Council approved certain rules to be followed for the Māhele that was drafted by Hawaiian Chief Justice William Lee. After submitting the rules for consideration, Chief Justice Lee stated:

In submitting the above rules to the consideration of You Majesty, I beg to state that I believe these rules to be such as are dictated by the Constitution and Laws of Your Kingdom and by the liberal and bountiful spirit which it has pleased Your Majesty to manifest for the good of Your Nation. It is my firm conviction that this silent and bloodless in the landed tenures of Your Kingdom will be the most blessed change that has ever fallen to the lot of Your Nation. It will remove the mountain of oppression that has hither to rested upon the productiveness of your soil, unbind the fetters of industry and wealth, and give a life and action to the dormant resources of Your Kingdom, which cover your land with the stream of prosperity and gladness. It is difficult at this day to foresee the bright results of this momentous change. I am aware that the division of lands between the Chiefs and Tenants of Your Kingdom will be attended with a multitude of difficulties. I cannot say that the great mass of Your Nation are full prepared to receive so great an Emancipation. They may spurn this proposed freedom. But I do not sincerely believe, that this great measure, by raising the Hawaiian Nation from a state of hereditary servitude, to that of a free and independent right in the soil they cultivate, will promote industry and agriculture, check depopulation, and ultimately prove the salvation of Your People. I believe it to be a measure which will meet the approval of Your Majesty in years to come, and cause your name to be remembered with veneration and gratitude by generations yet unborn. I believe that if this measure be fully carried out in the liberal spirit in which it is begun, if the lands of Your Majesty’s Kingdom be unlocked, it will open the hidden fountains of prosperity, and prove the dawn of a new and bright era to Your Kingdom.