The term “war crimes” was not coined until 1919 after the First World War ended in Europe. A common misunderstanding is that individuals whose criminal conduct constituted a war crime could only be prosecuted if that conduct arose after 1919. This is not the case because under the principles of international law, war crimes could have been committed since, at least, 1874, when delegates of fifteen European States gathered in Brussels, Belgium, at the request of Russia’s Czar Alexander II, in order to draft an international agreement concerning the laws and customs of war.

Among these fifteen States an agreement was made, but it wasn’t ratified by these States. It did, however, lead to the adoption of the Manual of the Laws and Customs of War at Oxford in 1880. Both the Brussels Declaration and the Oxford Manual formed the basis of the two Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.

At the Peace Conference held in The Hague, Netherlands in 1899, countries from across the world met in order to codify what was already accepted as customary international law regarding the rules of warfare and occupation, which is known today as international humanitarian law. The cornerstone of international humanitarian law during the occupation of a State is the duty of the occupying State to administer the laws of the occupied State, which is reflected in Article 43 of the 1899 Hague Convention, II.

Article 43 states, “The authority of the legitimate power having actually passed into the hands of the occupant, the latter shall take all steps in his power to re-establish and insure, as far as possible, public order and safety, while respecting, unless absolutely prevented, the laws in force in the country.” This article is a combination of Article 2, “The authority of the legitimate Power being suspended and having in fact passed into the hands of the occupants, the latter shall take all the measures in his power to restore and ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety,” and Article 3, “With this object he shall maintain the laws which were in force in the country in time of peace, and shall not modify, suspend or replace them unless necessary,” of the 1874 Brussels Declaration. The Brussels Declaration was referenced in the Preamble of the 1899 Hague Convention, II. Article 43 was restated in the 1907 Hague Convention, IV.

Although the United States signed and ratified both the 1899 and the 1907 Hague Regulations, which post-date the occupation of the Hawaiian Islands, the “text of Article 43,” according to Benvenisti, author of The International Law of Occupation (1993), p. 8, “was accepted by scholars as mere reiteration of the older law, and subsequently the article was generally recognized as expressing customary international law.” Graber, author of The Development of the Law of Belligerent Occupation: 1863-1914 (1949), p. 143, also states, that “nothing distinguishes the writing of the period following the 1899 Hague code from the writing prior to that code.”

As an occupying State, the United States was obligated to establish a military government, whose purpose would be to provisionally administer the laws of the occupied State—the Hawaiian Kingdom—until a treaty of peace or agreement to terminate the occupation has been done. According to United States Army Field Manual 27-10 (1956), sec. 362, “Military government is the form of administration by which an occupying power exercises governmental authority over occupied territory.” The administration of occupied territory is set forth in the Hague Regulations, being Section III of the 1907 HC IV. According to Schwarzenberger, author of “The Law of Belligerent Occupation: Basic Issues,” 30 Nordisk Tidsskrift Int’l Ret (1960), p. 11, “Section III of the Hague Regulations … was declaratory of international customary law.”

Also, consistent with what was generally considered the international law of occupation in force at the time of the Spanish-American War, the “military governments established in the territories occupied by the armies of the United States were instructed to apply, as far as possible, the local laws and to utilize, as far as seemed wise, the services of the local Spanish officials (Munroe Smith, “Record of Political Events,” 13(4) Political Science Quarterly (1898), 745, p. 748).”

Many other authorities also viewed the 1907 Hague Regulations as mere codification of customary international law, which was applicable at the time of the overthrow of the Hawaiian government and subsequent occupation. These include: Gerhard von Glahn, The Occupation of Enemy Territory: A Commentary on the Law and Practice of Belligerent Occupation (1957), 95; David Kretzmer, The Occupation of Justice: The Supreme Court of Israel and the Occupied Territories (2002), 57; Ludwig von Kohler, The Administration of the Occupied Territories, vol. I, (1942) 2; United States Judge Advocate General’s School Tex No. 11, Law of Belligerent Occupation (1944), 2 (stating that “Section III of the Hague Regulations is in substance a codification of customary law and its principles are binding signatories and non-signatories alike”).

The contracting States to the 1899 Hague Convention, II, also recognized that they were codifying existing customary international law and not creating new law. In its Preamble, it states, “Until a more complete code of the laws of war is issued, the High Contracting Parties think it right to declare that in cases not included in the Regulations adopted by them, populations and belligerents remain under the protection and empire of the principles of international law, as they result from the usages established between civilized nations, from the laws of humanity, and the requirements of the public conscience.” This particular provision of the Preamble has come to be known as the Martens clause. Professor von Martens was the Russian delegate at the 1899 Hague Peace Conference, that recommended this provision be placed in the Preamble after the delegates were unable to agree on the status of civilians who took up arms against the occupying State.

The Commission on the Responsibility of the Authors of the War and on Enforcement of Penalties was established at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 after World War I. Its role was to investigate the allegations of war crimes and recommend who should be prosecuted. In its report (Pamphlet No. 32, p. 18), the Commission identified 32 war crimes, two of which were “usurpation of sovereignty during military occupation” and “attempts to denationalise the inhabitants of occupied territory.”

Although these crimes were not specifically identified in 1899 Hague Convention, II, or the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, the Commission relied solely on the Martens clause in the 1899 Hague Convention, II. In other words, the Commission concluded that the war crimes of “usurpation of sovereignty during military occupation” and “attempts to denationalise the inhabitants of occupied territory” were recognized under principles of international law since at least the 1874 Brussels Declaration.

Under the war crime of usurpation of sovereignty during military occupation, the Commission concluded that from 1915-1918, Bulgaria engaged in criminal conduct when it “Proclaimed that the Serbian State no longer existed, and that Serbian territory had become Bulgarian,” and that “official orders show efforts of Bulgarisation (Pamphlet No. 32, p. 38).” The Commission also concluded Bulgaria committed the following acts of usurpation of sovereignty:

- Serbian law, courts, and administration ousted

- Taxes collected under Bulgarian fiscal regime

- Serbian currency suppressed

- Public property removed or destroyed, including books, archives and MSS (g., from the National Library, the University Library, Serbian Legation at Sofia, French Consulate at Uskub)

- Prohibited sending Serbian Red Cross to occupied Serbia

The Commission also concluded that Austrian and German authorities also engaged in the following criminal conduct of usurpation of sovereignty during military occupation from 1915 to 1918 during the occupation of Serbia (Pamphlet No. 32, p. 38).

- The Austrians suspended many Serbian laws and substituted their own, especially in penal matters, in procedure, judicial reorganization, &c.

- Museums belonging to the State (g., Belgrade, Detchani) were emptied and the contents taken to Vienna

Under the war crime of attempts to denationalize the inhabitants of occupied territory, the Commission concluded that from 1915-1918, Bulgaria engaged in the following criminal conduct in occupied Serbia (Pamphlet No. 32, p. 39).

- Efforts to impose their national characteristics on the population

- Serbian language forbidden in private as well as official relations

- People beaten for saying “Good morning” in Serbian

- Inhabitants forced to give their names a Bulgarian form

- Serbian books banned—were systematically destroyed

- Archives of churches and law courts destroyed

- Schools and churches closed, sometimes destroyed

- Bulgarian schools and churches substituted—attendance at school made compulsory

- Population forced to be present at Bulgarian national solemnities

The Commission also concluded that Austrian and German authorities also engaged in the following criminal conduct of attempts to denationalize the inhabitants of occupied territory from 1915 to 1918 during the occupation of Serbia (Pamphlet No. 32, p. 39).

- Austrians and Germans interfered with religious worship, by deportation of priests and requisition of churches for military purposes

- Interfered with use of Serbian language

The prosecution of German officials and their Allies for war crimes committed during World War I, however, was dismal. Of 5,000 individuals reported for war crimes only 12 were tried and 6 were convicted. Despite this failure, it was the beginning of imposing criminal liability on individuals for violations of international law that eventually became firmly grounded after the Second World War, which led to war crimes legislation in countries who were contracting parties to the 1949 Geneva Conventions, and also the establishment of the International Criminal Court.

Under the principles of international law, officials of the United States were capable of committing war crimes when the Hawaiian Kingdom was first invaded on January 16, 1893 and occupied since January 17 when the Hawaiian government was unlawfully seized. The criminal conduct committed by German, Austrian and Bulgarian officials against Serbia and its people during the First World War (1914-1918) are very similar to the criminal conduct by the United States since January 16, 1893 against the Hawaiian Kingdom and its people.

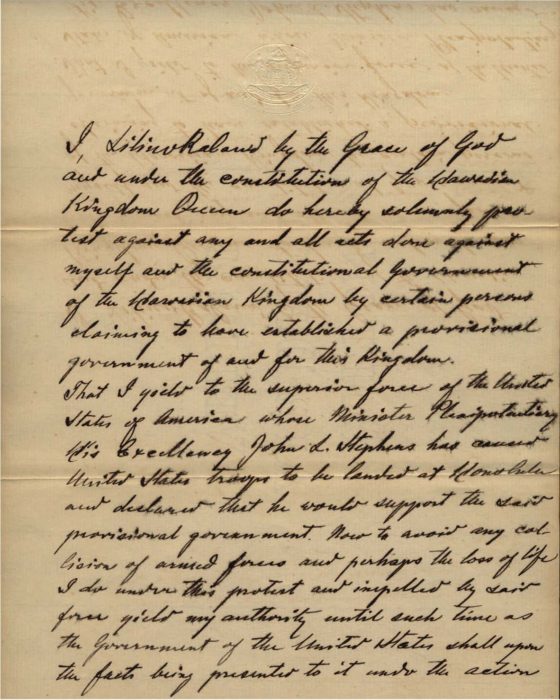

These two days will mark 125 years of the American invasion of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 16th and the conditional surrender of the Hawaiian government by Queen Lili‘uokalani on January 17th calling upon the President of the United States to investigate the unlawful actions taken by its diplomat who ordered the landing of U.S. troops. While in the Palace, the Queen drafted the following conditional surrender to the United States:

These two days will mark 125 years of the American invasion of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 16th and the conditional surrender of the Hawaiian government by Queen Lili‘uokalani on January 17th calling upon the President of the United States to investigate the unlawful actions taken by its diplomat who ordered the landing of U.S. troops. While in the Palace, the Queen drafted the following conditional surrender to the United States:

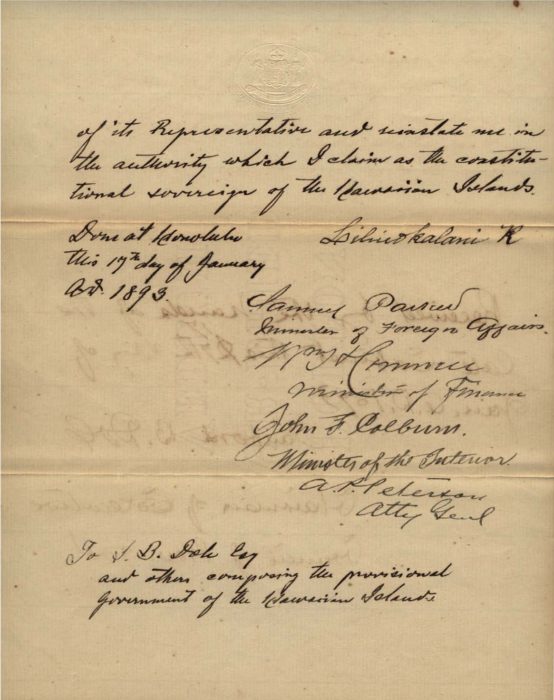

After investigating the overthrow of the Hawaiian government, President Cleveland

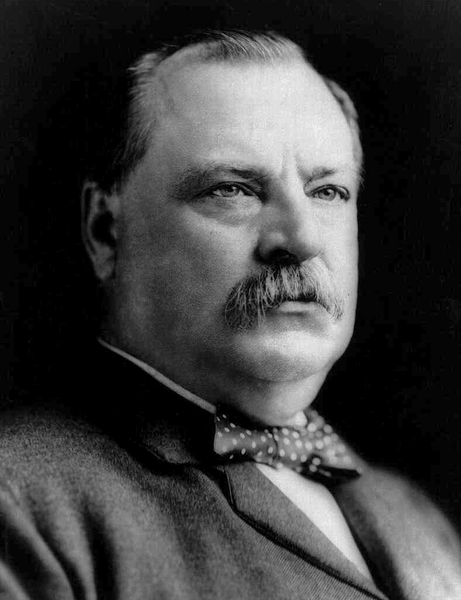

After investigating the overthrow of the Hawaiian government, President Cleveland  The political determination by President Cleveland, regarding the actions taken by the military forces of the United States since January 16, 1893, was the same as the political determination by President Roosevelt regarding actions taken by the military forces of Japan on December 7, 1945 in its attack of Pearl Harbor. On December 8, 1941, President Roosevelt

The political determination by President Cleveland, regarding the actions taken by the military forces of the United States since January 16, 1893, was the same as the political determination by President Roosevelt regarding actions taken by the military forces of Japan on December 7, 1945 in its attack of Pearl Harbor. On December 8, 1941, President Roosevelt  Professor William Schabas

Professor William Schabas

member of the International Commission of Inquiry in

member of the International Commission of Inquiry in