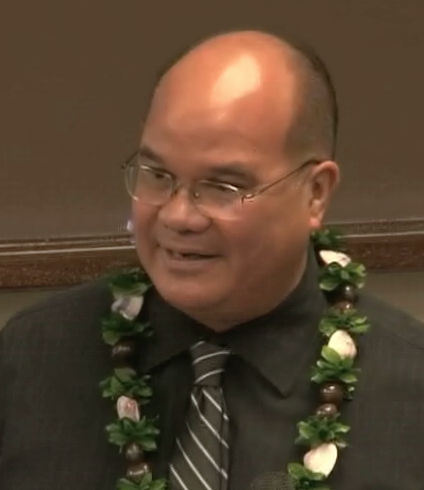

In a move to bring international attention to the humanitarian crisis in the Hawaiian Islands as a result of the United States prolonged and illegal occupation since the Spanish-American War, a Complaint was submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Council (Council) on May 23, 2016. Dr. Keanu Sai represents the complainant, Kale Kepekaio Gumapac, as his attorney-in-fact. Dr. Sai also represents Gumapac before Swiss authorities regarding war crimes. Additional documents that accompanied the Complaint, included: War Crimes Report: Humanitarian Crisis in the Hawaiian Islands by Dr. Sai, his Declaration and Curriculum Vitae.

In a move to bring international attention to the humanitarian crisis in the Hawaiian Islands as a result of the United States prolonged and illegal occupation since the Spanish-American War, a Complaint was submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Council (Council) on May 23, 2016. Dr. Keanu Sai represents the complainant, Kale Kepekaio Gumapac, as his attorney-in-fact. Dr. Sai also represents Gumapac before Swiss authorities regarding war crimes. Additional documents that accompanied the Complaint, included: War Crimes Report: Humanitarian Crisis in the Hawaiian Islands by Dr. Sai, his Declaration and Curriculum Vitae.

“The lodging of the complaint was two-fold,” explains Dr. Sai. “First, the complaint will draw attention to the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which has created a humanitarian crisis of unimaginable proportions never before seen. Second, the purpose of the complaint is to report the war crimes committed against Kale Gumpac by Deutsche Bank, officials of the State of Hawai‘i, and others, which is now before the Swiss Federal Criminal Court. As a victim of war crimes, Mr. Gumapac is one of thousands, if not millions of victims who reside in Hawai‘i under an illegal foreign occupation.”

“The lodging of the complaint was two-fold,” explains Dr. Sai. “First, the complaint will draw attention to the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, which has created a humanitarian crisis of unimaginable proportions never before seen. Second, the purpose of the complaint is to report the war crimes committed against Kale Gumpac by Deutsche Bank, officials of the State of Hawai‘i, and others, which is now before the Swiss Federal Criminal Court. As a victim of war crimes, Mr. Gumapac is one of thousands, if not millions of victims who reside in Hawai‘i under an illegal foreign occupation.”

The Council was established in 2006 by the United Nations General Assembly and was formerly known as the United Nations Commission on Human Rights. The General Assembly gave the Council two main responsibilities: (a) promote universal respect for the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms for all, without distinction of any kind and in a fair and equal manner; and (b) address situations of violations of human rights, including gross and systematic violations, and make recommendations to resolve them. The Council is comprised of 47 member States of the United Nations who are elected by the United Nations General Assembly for a term of three years.

The Council has a human rights mandate, but has also included as part of its mandate international humanitarian law. International human rights law are rights inherent in all human beings, whatever their nationality, place of residence, sex, national or ethnic origin, color, religion, language, or any other status. These rights are expressed in treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. International humanitarian law is a set of rules to protect civilians and non-combatants during an armed conflict, which includes military occupation. Humanitarian law is expressed in treaties such as the 1907 Hague Convention, IV, and the 1949 Geneva Convention, IV.

In the past, it was thought that human rights law applied only during peace time and humanitarian law applied only during armed conflict, but current international law recognizes that both bodies of law are considered as complementary sources of obligations in situations of armed conflict. In its 2008 Resolution 9/9—Protection of the human rights of civilians in armed conflict, the Council emphasized “that conduct that violates international humanitarian law, including grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, or of the Protocol Additional there of 8 June 1977 relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), may also constitute a gross violation of human rights.”

The Council then reiterated “that effective measures to guarantee and monitor the implementation of human rights should be taken in respect of civilian populations in situations of armed conflict, including people under foreign occupation, and that effective protection against violations of their human rights should be provided, in accordance with international human rights law and applicable international humanitarian law, particularly Geneva Convention IV relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, of 12 August 1949, and other international instruments.”

Accompanying the Complaint is a War Crime Report that provides a comprehensive narrative of Hawai‘i’s legal and political history since the nineteenth century to the present. In the Report, Dr. Sai explains, “The Report will answer, in the affirmative, three fundamental questions that are quintessential to the current situation in the Hawaiian Islands:

- Did the Hawaiian Kingdom exist as an independent State and a subject of international law?

- Does the Hawaiian Kingdom continue to exist as an independent State and a subject of International Law, despite the illegal overthrow of its government by the United States?

- Have war crimes been committed in violation of international humanitarian law?”

After answering these questions in the affirmative, Dr. Sai would then conclude that the UNHRC has the authority to investigate the complaint “under the complaint procedure provided for in paragraph 87 of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 5/1.”

Before providing the facts of Gumapac’s case, the Complaint gives a short summary of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as a State under international law, and that this status was explicitly recognized by the Secretariat of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in Lance Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom (1999-2001).

In the Complaint, Dr. Sai states, “Since the occupation began, the United States engaged in the criminal conduct of genocide under humanitarian law through denationalization. After local institutions of Hawaiian self-government were destroyed by the United States through its installed insurgency, a United States pattern of administration was imposed in 1900, whereby the former Hawaiian national character was obliterated.”

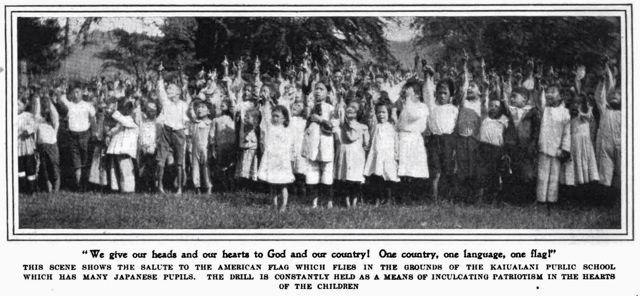

Dr. Sai went on to provide a pattern of criminal conduct in violation of international humanitarian law: “The United States interfered with the methods of education; compelled education in the English language; banned the use of Hawaiian, being the national language, in the schools; compulsory or automatic granting of United States citizenship upon Hawaiian nationals; imposed conscription of Hawaiian nationals into the armed forces of the United States; imposed the duty of swearing the oath of allegiance; confiscated and destroyed property of Hawaiian nationals for militarization; pillaged the property and estates of Hawaiian nationals; imposed American administrative and judicial systems; imposed American financial and economic administration; colonized Hawaiian territory with nationals of the United States; permeated the economic life through individuals whose nationality and/or allegiance was American; and denied Hawaiian nationals of aboriginal blood their vested right to health care at no charge at Queen’s Hospital, which was established by the Hawaiian government for that purpose.”

The Complaint calls upon the Council to take action without haste and recommends the Council to:

- Strongly call upon the Government of the United States of America and its armed force, the State of Hawai‘i, to take urgent measures to comply fully with their obligations under international law, including international humanitarian law and human rights law;

- Underline that the Government of the United States of America has the primary responsibility to make every effort to strengthen the protection of the civilian population in the Hawaiian Islands and to investigate and bring to justice perpetrators of violations of human rights and international humanitarian law; and

- Appoint a Special Rapporteur on the humanitarian crisis in the Hawaiian Islands given the gravity and severity of an illegal and prolonged occupation of an independent State that has been allowed to continue unfettered without precedent in the history of international relations.

Additionally, the Council oversees a process called Universal Periodic Review (UPR), which involves a review of the human rights records of all member States of the United Nations, which includes its record of complying with international humanitarian law. In UPRs, the Council decided in its Resolution 5/1 that “given the complementary and mutually interrelated nature of international human rights law and international humanitarian law, the review shall taken into account applicable international humanitarian law.”

In the Complaint, Dr. Sai also draws attention to the UPR done on the United States in 2015. “The February 6, 2015 Report of the United States submitted to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in Conjunction with the Universal Periodic Review deliberately withheld information of the Hawaiian Kingdom despite the United States’ full and complete knowledge of arbitration proceedings held under the auspices of the PCA, and where the Secretariat of the PCA explicitly recognized the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom.”

Dr. Sai further states that “the draft report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review of the United States dated May 21, 2015, and the final report of the United Nations Human Rights Council adopted on September 24, 2015, omits any mention of the Hawaiian Kingdom as well.” Instead, the 2015 UPR of the United States treats native Hawaiians as an indigenous people, which, under United Nations instruments, are nations of people that are non-States and reside within the territory of a State, such as Native American tribes. Common words that are associated with indigenous people include terms such as self-determination, colonization, and decolonization.

The 2015 UPR reflects the deception that has been perpetuated by the United States in order to conceal its prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom that has now lasted for over a century, and the genocide of the Hawaiian citizenry who have been led to believe that aboriginal Hawaiians are an indigenous people that have been colonized by the United States. In the Complaint, Dr. Sai states, “Hawaiian nationals of aboriginal blood are not indigenous people as defined under United Nations instruments, but are defined under Hawaiian Kingdom law as Hawaiian subjects who comprise the majority of the national population.”

The American occupation of Hawai‘i is the longest occupation in the history of international relations, and it will be a shock for the international community to find out that the United States seized an internationally recognized neutral country in order to bolster its military, and carried out a policy of genocide through denationalization in violation of international humanitarian law. This policy that was carried out in 1900 resulted in the obliteration of Hawaiian national consciousness among the citizenry of the Hawaiian Kingdom in less then two generations.

https://vimeo.com/168241369

Dr. Lynette Cruz interviews Dr. Sai on the topic of genocide through denationalization on her television show, Issues that Matter. Dr. Sai explains the difference between international humanitarian law and human rights law, and how genocide has and continues to occur through denationalization of Hawaiian subjects.