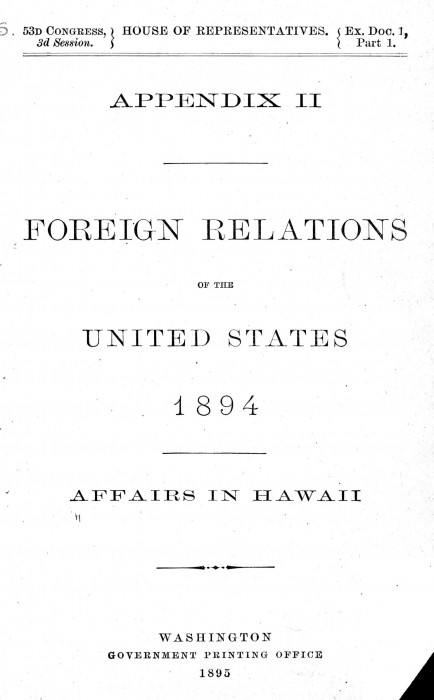

There has been recent attention drawn to Andrew Walden’s article titled “Liliuokalani 1895: “Monarchy is Forever Ended, Republic of Hawaii is only lawful Government.” He claims the monarchy had ended in 1895 and that the Republic of Hawai‘i had become the lawful government. What Walden leaves out of his article is that the Republic of Hawai‘i, who the United States Congress in its Apology resolution in 1993 called “self-declared,” was comprised of insurgents. After completing a presidential investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government by United States forces, President Cleveland secured an executive agreement with Queen Lili‘uokalani to grant amnesty after the Hawaiian Kingdom government was restored under the 1893 Agreement of restoration. The failure of the President to carry out the Agreement of restoration, being an international treaty, is what allowed the insurgency to increase its unlawful power and control over the Hawaiian Islands. What is also interesting is that Walden admits that Lili‘uokalani was still Queen after the so-called overthrow of January 17, 1893.

There has been recent attention drawn to Andrew Walden’s article titled “Liliuokalani 1895: “Monarchy is Forever Ended, Republic of Hawaii is only lawful Government.” He claims the monarchy had ended in 1895 and that the Republic of Hawai‘i had become the lawful government. What Walden leaves out of his article is that the Republic of Hawai‘i, who the United States Congress in its Apology resolution in 1993 called “self-declared,” was comprised of insurgents. After completing a presidential investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government by United States forces, President Cleveland secured an executive agreement with Queen Lili‘uokalani to grant amnesty after the Hawaiian Kingdom government was restored under the 1893 Agreement of restoration. The failure of the President to carry out the Agreement of restoration, being an international treaty, is what allowed the insurgency to increase its unlawful power and control over the Hawaiian Islands. What is also interesting is that Walden admits that Lili‘uokalani was still Queen after the so-called overthrow of January 17, 1893.

Walden also fails to mention that the Queen was not an absolute Monarch, but rather a constitutional monarch limited and confined to Hawaiian law as the Chief Executive, which was distinct from the Judicial and Legislative branches of Hawaiian government. The Queen, as Chief Executive, could no more terminate the Hawaiian Kingdom by threat of insurgents, than the President, as Chief Executive of the United States, could terminate the Republic by threat of terrorists.

So according to this logic, if terrorists somehow kidnap the President of the United States and have him sign an abdication of the Republic of the United States and recognizes Al Qaeda as the lawful government in order to save the lives of some of his countrymen, the United States of America ceases to exist? This is a ridiculous notion, but it could be a great story line for an episode of “24: Live Another Day.” Putting all fun aside, the best explanation of the crisis would come from the law and from the Queen herself in her autobiography “Hawai‘i’s Story by Hawai‘i’s Queen” (1898). Under Chapters XLIII and XLIV the Queen explained in her own words:

I am Placed Under Arrest

On the sixteenth day of January, 1895, Deputy Marshal Arthur Brown and Captain Robert Waipa Parker were seen coming up the walk which leads from Beretania Street to my residence. Mrs. Wilson told me that they were approaching. I directed her to show them into the parlor, where I soon joined them. Mr. Brown informed me that he had come to serve a warrant for my arrest; he would not permit me to take the paper which he held, nor to examine its contents.

It was evident they expected me to accompany them; so I made preparations to comply, supposing that I was to be taken at once to the station-house to undergo some kind of trial. I was informed that I could bring Mrs. Clark with me if I wished, so she went for my hand-bag; and followed by her, I entered the carriage of the deputy marshal, and was driven through the crowd that by this time had accumulated at the gates of my residence at Washington Place. As I turned the corner of the block on which is built the Central Congregational church, I noticed the approach from another direction of Chief Justice Albert F. Judd; he was on the sidewalk, and was going toward my house, which he entered. In the mean time the marshal’s carriage continued on its way, and we arrived at the gates of Iolani Palace, the residence of the Hawaiian sovereigns.

We drove up to the front steps, and I remember noticing that troops of soldiers were scattered all over the yard. The men looked as though they had been on the watch all night. They were resting on the green grass, as though wearied by their vigils; and their arms were stacked near their tents, these latter having been pitched at intervals all over the palace grounds. Staring directly at us were the muzzles of two brass field pieces, which looked warlike and formidable as they pointed out toward the gate from their positions on the lower veranda. Colonel J. H. Fisher came down the steps to receive me; I dismounted, and he led the way up the staircase to a large room in the corner of the palace. Here Mr. Brown made a formal delivery of my person into the custody of Colonel Fisher, and having done this, withdrew.

Then I had an opportunity to take a survey of my apartments. There was a large, airy, uncarpeted room with a single bed in one corner. The other furniture consisted of one sofa, a small square table, one single common chair, and iron safe, a bureau, a chiffonier, and a cupboard, intended for eatables, made of wood with wire screening to allow the circulation of the air through the food. Some of these articles may have been added during the days of my imprisonment. I have portrayed the room as it appears to me in memory. There was, adjoining the principal apartment, a bath-room, and also a corner room and a little boudoir, the windows of which were large, and gave access to the veranda.

Colonel Fisher spoke very kindly as he left me there, telling me that he supposed this was to be my future abode; and if there was anything I wanted I had only to mention it to the officer, and that it should be provided. In reply, I informed him that there were one or two of my attendants whom I would like to have near me, and that I preferred to have my meals sent from my own house. As a result of this expression of my wishes, permission was granted to my steward to bring me my meals three times each day.

That first night of my imprisonment was the longest night I have ever passed in my life; it seemed as though the dawn of day would never come. I found in my bag a small Book of Common Prayer according to the ritual of the Episcopal Church. It was a great comfort to me, and before retiring to rest Mrs. Clark and I spent a few minutes in the devotions appropriate to the evening.

Here, perhaps, I may say, that although I had been a regular attendant on the Presbyterian worship since my childhood, a constant contributor to all the missionary societies, and had helped to build their churches and ornament the walls, giving my time and my musical ability freely to make their meetings attractive to my people, yet none of these pious church members or clergymen remembered me in my prison. To this (Christian?) conduct I contrast that of the Anglican bishop, Rt. Rev. Alfred Willis, who visited me from time to time in my house, and in whose church I have since been confirmed as a communicant. But he was not allowed to see me at the palace.

Outside of the rooms occupied by myself and my companion there were guards stationed by day and by night, whose duty it was to pace backward and forward through the hall, before my door, and up and down the front veranda. The sound of their never-ceasing footsteps as they tramped on their beat fell incessantly on my ears. One officer was in charge, and two soldiers were always detailed to watch our rooms. I could not but be reminded every instant that I was a prisoner, and did not fail to realize my position. My companion could not have slept at all that night; her sighs were audible to me without cessation; so I told her the morning following that, as her husband was in prison, it was her duty to return to her children. Mr. Wilson came in after I had breakfasted, accompanied by the Attorney-general, Mr. W. O. Smith; and in conference it was agreed between us that Mrs. Clark could return home, and that Mrs. Wilson should remain as my attendant; that Mr. Wilson would be the person to inform the government of any request to be made by me, and that any business transactions might be made through him.

On the morning after my arrest all my retainers residing on my estates were arrested, and to the number of about forty persons were taken to the station-house, and then committed to jail. Amongst these was the agent and manager of my property, Mr. Joseph Heleluhe. As Mr. Charles B. Wilson had been at one time in a similar position, and was well acquainted with all my surroundings, and knew the people about me, it was but natural that he should be chosen by me for this office.

Mr. Heleluhe was taken by the government officers, stripped of all clothing, placed in a dark cell without light, food, air, or water, and was kept there for hours in hopes that the discomfort of his position would induce him to disclose something of my affairs. After this was found to be fruitless, he was imprisoned for about six weeks; when, finding their efforts in vain, his tormentors released him. No charge was ever brought against him in any way, which is true of about two hundred persons who were similarly confined.

On the very day I left the house, so I was informed by Mr. Wilson, Mr. A. F. Judd had gone to my private residence without search-warrant; and that all the papers in my desk, or in my safe, my diaries, the petitions I had received from my people, – all things of that nature which could be found were swept into a bag, and carried off by the chief justice in person. My husband’s private papers were also included in those taken from me.

To this day, the only document which has been returned to me is my will. Never since have I been able to find the private papers of my husband nor of mine that had been kept by me for use or reference, and which had no relation to political events. The most important historical note lost was in my diary. This was the record made by me at the time of my conversations with Minister Willis, and would be especially valuable now as confirming what I have stated of our first interview.

After Mr. Judd had left my house, it was turned over to the Portuguese military company under the command of Captain Good. These militiamen ransacked it again from garret to cellar. Not an article was left undisturbed. Before Mr. Judd had finished they had begun their work, and there was no trifle left unturned to see what might be hidden beneath. Every drawer of desk, table, or bureau was wrenched out, turned upside down, the contents pulled over on the floors, and left in confusion there. Some of my husband’s jewelry was taken; but this, in my application and offer to pay expenses, was afterwards restored to me.

Having overhauled the rooms without other result than the abstraction of many memorandums of no use to any other person besides myself, the men turned their attention to the cellar, in hopes possibly of unearthing an arsenal of firearms and munitions of war. Here they undermined the foundations to such a degree as to endanger the whole structure, but nothing rewarded their search. The place was then seized, and the government assumed possession; guards were placed on the premises, and no one was allowed to enter.

Imprisonment—Forced Abdication

For the first few days nothing occurred to disturb the quiet of my apartments save the tread of the sentry. On the fourth day I received a visit from Mr. Paul Neumann, who asked me if, in the event that it should be decided that all the principal parties to the revolt must pay for it with their lives, I was prepared to die? I replied to this in the affirmative, telling him I had no anxiety for myself, and felt no dread of death. He then told me that six others besides myself had been selected to be shot for treason, but that he would call again, and let me know further about our fate. I was in a state of nervous prostration, as I have said, at the time of the outbreak, and naturally the strain upon my mind had much aggravated my physical troubles; yet it was with much difficulty that I obtained permission to have visits from my own medical attendant.

About the 22d of January a paper was handed to me by Mr. Wilson, which, on examination, proved to be a purported act of abdication for me to sign. It had been drawn out for the men in power by their own lawyer, Mr. A. S. Hartwell, whom I had not seen until he came with others to see me sign it. The idea of abdicating never originated with me. I knew nothing at all about such a transaction until they sent to me, by the hands of Mr. Wilson, the insulting proposition written in abject terms. For myself, I would have chosen death rather than to have signed it; but it was represented to me that by my signing this paper all the persons who had been arrested, all my people now in trouble by reason of their love and loyalty towards me, would be immediately released. Think of my position, —sick, a lone woman in prison, scarcely knowing who was my friend, or who listened to my words only to betray me, without legal advice or friendly counsel, and the stream of blood ready to flow unless it was stayed by my pen.

My persecutors have stated, and at that time compelled me to state, that this paper was signed and acknowledged by me after consultation with my friends whose names appear at the foot of it as witnesses. Not the least opportunity was given to me to confer with any one; but for the purpose of making it appear to the outside world that I was under the guidance of others, friends who had known me well in better days were brought into the place of my imprisonment, and stood around to see a signature affixed by me.

When it was sent to me to read, it was only a rough draft. After I had examined it, Mr. Wilson called, and asked me if I were willing to sign it. I simply answered that I would see when the formal or official copy was shown me. On the morning of the 24th of January the official document was handed to me, Mr. Wilson making the remark, as he gave it, that he hoped I would not retract, that is, he hoped that I would sign the official copy.

Then the following individuals witnessed my subscription of the signature which was demanded of me: William G. Irwin, H. A. Widemann, Samuel Parker, S. Kalua Kookano, Charles B. Wilson, and Paul Neumann. The form of acknowledgment was taken by W. L. Stanley, Notary Public.

So far from the presence of these persons being evidence of a voluntary act on my part, was it not an assurance to me that they, too, knew that, unless I did the will of my jailers, what Mr. Neumann had threatened would be performed, and six prominent citizens immediately put to death. I so regarded it then, and I still believe that murder was the alternative. Be this as it may, it is certainly happier for me to reflect today that there is not a drop of the blood of my subjects, friends or foes, upon my soul.

When it came to the act of writing, I asked what would be the form of signature; to which I was told to sign, “Liliuokalani Dominis.” This sounding strange to me, I repeated the question, and was given the same reply. At this I wrote what they dictated without further demur, the more readily for the following reasons.

Before ascending the throne, for fourteen years, or since the date of my proclamation as heir apparent, my official title had been simply Liliuokalani. Thus I was proclaimed both Princess Royal and Queen. Thus it is recorded in the archives of the government to this day. The Provisional Government nor any other had enacted any change in my name. All my official acts, as well as my private letters, were issued over the signature of Liliuokalani. But when my jailers required me to sign “Liliuokalani Dominis,” I did as they commanded. Their motive in this as in other actions was plainly to humiliate me before my people and before the world. I saw in a moment, what they did not, that, even were I not complying under the most severe and exacting duress, by this demand they had overreached themselves. There is not, and never was, within the range of my knowledge, any such a person as Liliuokalani Dominis.

It is a rule of common law that the acts of any person deprived of civil rights have no force nor weight, either at law or in equity; and that was my situation. Although it was written in the document that it was my free act and deed, circumstances prove that it was not; it had been impressed upon me that only by its execution could the lives of those dear to me, those beloved by the people of Hawaii, be saved, and the shedding of blood be averted. I have never expected the revolutionists of 1887 and 1893 to willingly restore the rights notoriously taken by force or intimidation; but this act, obtained under duress, should have no weight with the authorities of the United States, to whom I appealed. But it may be asked, why did I not make some protest at the time, or at least shortly thereafter, when I found my friends sentenced to death and imprisonment? I did. There are those now living who have seen my written statement of all that I have recalled here. It was made in my own handwriting, on such paper as I could get, and sent outside of the prison walls and into the hands of those to whom I wished to state the circumstances under which that fraudulent act of abdication was procured from me. This I did for my own satisfaction at the time.

After those in my place of imprisonment had all affixed their signatures, they left, with the single exception of Mr. A. S. Hartwell. As he prepared to go, he came forward, shook me by the hand, and the tears streamed down his cheeks. This was a matter of great surprise to me. After this he left the room. If he had been engaged in a righteous and honorable action, why should he be affected? Was it the consciousness of a mean act which overcame him so? Mrs. Wilson, who stood behind my chair throughout the ceremony, made the remark that those were crocodile’s tears. I leave it to the reader to say what were his actual feelings in the case.

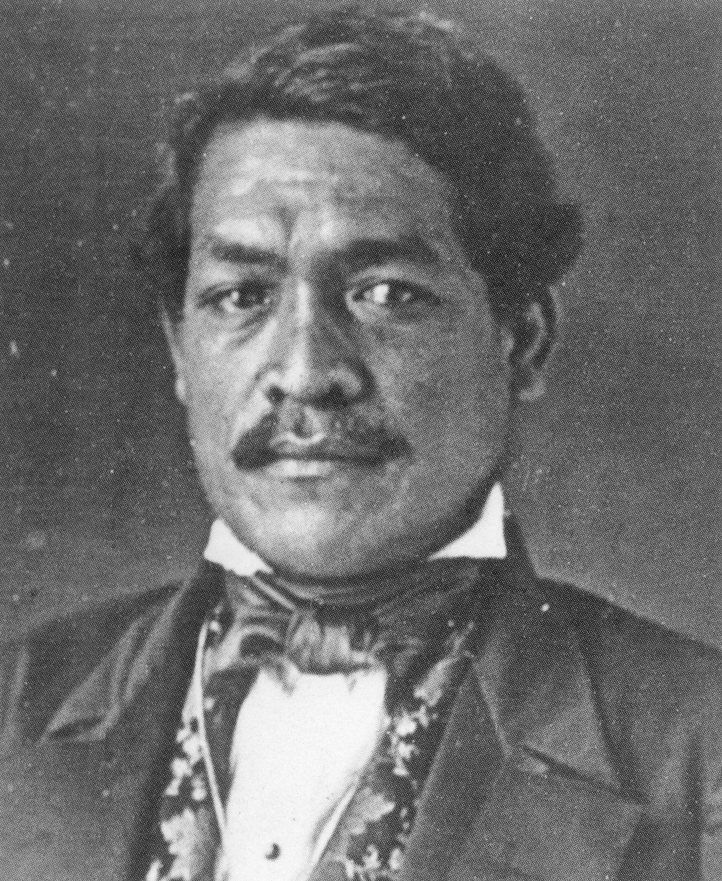

In the summer of 1842, Kamehameha III moved forward to secure the position of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a recognized independent state under international law. He sought the formal recognition of Hawaiian independence from the three naval powers of the world at the time—Great Britain, France, and the United States. To accomplish this, Kamehameha III commissioned three envoys, Timoteo Ha‘alilio, William Richards, who at the time was still an American Citizen, and Sir George Simpson, a British subject. Of all three powers, it was the British that had a legal claim over the Hawaiian Islands through cession by Kamehameha I, but for political reasons the British could not openly exert its claim over the other two naval powers. Due to the islands prime economic and strategic location in the middle of the north Pacific, the political interest of all three powers was to ensure that none would have a greater interest than the other. This caused Kamehameha III “considerable embarrassment in managing his foreign relations, and…awakened the very strong desire that his Kingdom shall be formally acknowledged by the civilized nations of the world as a sovereign and independent State.”

In the summer of 1842, Kamehameha III moved forward to secure the position of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a recognized independent state under international law. He sought the formal recognition of Hawaiian independence from the three naval powers of the world at the time—Great Britain, France, and the United States. To accomplish this, Kamehameha III commissioned three envoys, Timoteo Ha‘alilio, William Richards, who at the time was still an American Citizen, and Sir George Simpson, a British subject. Of all three powers, it was the British that had a legal claim over the Hawaiian Islands through cession by Kamehameha I, but for political reasons the British could not openly exert its claim over the other two naval powers. Due to the islands prime economic and strategic location in the middle of the north Pacific, the political interest of all three powers was to ensure that none would have a greater interest than the other. This caused Kamehameha III “considerable embarrassment in managing his foreign relations, and…awakened the very strong desire that his Kingdom shall be formally acknowledged by the civilized nations of the world as a sovereign and independent State.” While the envoys were on their diplomatic mission, a British Naval ship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843, making outrageous demands on the Hawaiian government. Basing his actions on complaints made to him in letters from the British Consul, Richard Charlton, who was absent from the kingdom at the time, Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25, 1843, after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom, but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats in Europe. News

While the envoys were on their diplomatic mission, a British Naval ship, HBMS Carysfort, under the command of Lord Paulet, entered Honolulu harbor on February 10, 1843, making outrageous demands on the Hawaiian government. Basing his actions on complaints made to him in letters from the British Consul, Richard Charlton, who was absent from the kingdom at the time, Paulet eventually seized control of the Hawaiian government on February 25, 1843, after threatening to level Honolulu with cannon fire. Kamehameha III was forced to surrender the kingdom, but did so under written protest and pending the outcome of the mission of his diplomats in Europe. News  of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in the islands on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto.

of Paulet’s action reached Admiral Richard Thomas of the British Admiralty, and he sailed from the Chilean port of Valparaiso and arrived in the islands on July 25, 1843. After a meeting with Kamehameha III, Admiral Thomas determined that Charlton’s complaints did not warrant a British takeover and ordered the restoration of the Hawaiian government, which took place in a grand ceremony on July 31, 1843. At a thanksgiving service after the ceremony, Kamehameha III proclaimed before a large crowd, ua mau ke ea o ka ‘aina i ka pono (the life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness). The King’s statement became the national motto.