FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

March 10, 2026

In a formal letter, dated March 3, 2026, from the International Seabed Authority’s (ISA) Secretary General, Letitia Carvalho, to Hawaiian Kingdom Minister of Foreign Affairs ad interim, Dr. David Keanu Sai, Ph.D., the ISA recognized the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State since the nineteenth century and its status as an Observer State. In her letter, the Secretary General clarifies the rules and practice of the ISA for a State to acquire observer status under Rule 82 of the Rules of Procedure of the Assembly of the ISA.

The ISA is an international organization that is composed of representatives of States that are Contracting States to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The headquarters of the ISA is in Kingston, Jamaica, where the Council and the Assembly of the ISA meet in session. Currently, the membership of the ISA is comprised of the European Union and 171 Contracting States to the UNCLOS.

According to its website, the “ISA is the organization through which States Parties to UNCLOS organize and control all mineral-resources-related activities in the Area for the benefit of humankind as a whole. In so doing, ISA has the mandate to ensure the effective protection of the marine environment from harmful effects that may arise from deep-seabed-related activities.”

For those States that have not acceded to the UNCLOS, participation is allowed if the States are granted observer status. While the Observer State is permitted to participate in the meetings, it has no voting rights. There are currently 27 Observer States that includes the United States.

Rule 82(a) of the Rules of Procedure of the Assembly provides “States and entities referred to in article 305 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea which are not members of the Authority,” can participate as Observers. Article 305(a) of the UNCLOS provides “all States” can become a Contracting State to the Convention. Though it is not yet a Contracting State and member to the UNCLOS pursuant to Article 305(a) of the Convention, the Hawaiian Kingdom has been acknowledged by the ISA as a State, as referred to in article 305 of the UNCLOS, and is consequently qualified to apply for participation as an “Observer” in meetings of the Assembly and of the Council of the ISA.

Since June of 2025, Minister Dr. Sai, in his official capacity as Minister of Foreign Affairs ad interim of the Hawaiian Kingdom, was in communication with the ISA that led to the formal recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the ISA on March 3, 2026.

In Minister Dr. Sai’s letter to Secretary General Carvalho, dated June 30, 2025, he stated, “The purpose of this letter is two-fold: first, to explain the circumstances of the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom for the purposes of international law and its impact on ISA members who are successor States of Hawaiian Kingdom treaty partners; and second, for the Hawaiian Kingdom to provide you notice of our intent to accede to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the 1994 Agreement relating to the implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 (with annex).”

Minister Dr. Sai sent a communication, dated July 28, 2025, to Ms. Mariana Durney, Legal Counsel and Director of the Office of Legal Counsel for the ISA, that provided the factual and legal basis for the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as a State, under international law, since the nineteenth century, and the Council of Regency as its interim government, so that it can pursue Observer State status under Rule 82 of the Rules of Procedure of the Assembly.

In a communication, dated September 2, 2025, to Secretary General Carvalho, Minister Dr. Sai stated, “Pending the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom accession to these international agreements and, thereby, becomes a Member State of the International Seabed Authority, we request observer status as a State in accordance with Article 305(1)(a) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, and Rule 82(1)(a) of the Rules of Procedure of the Assembly of the International Seabed Authority.”

On March 3, 2026, Minister Dr. Sai received an email, with an enclosed letter, from Ms. Durney, explaining the process by which the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a Non-Contracting State to the UNCLOS, needs to do in order to be granted Observer State status under Rule 82 (a) of the Rules of Procedure of the Assembly. In Ms. Durney’s letter, she referred to Minister Dr. Sai as “H.E. Dr. David Keanu Sai, Ph.D., Minister of Foreign Affairs ad interim, Hawaiian Kingdom.”

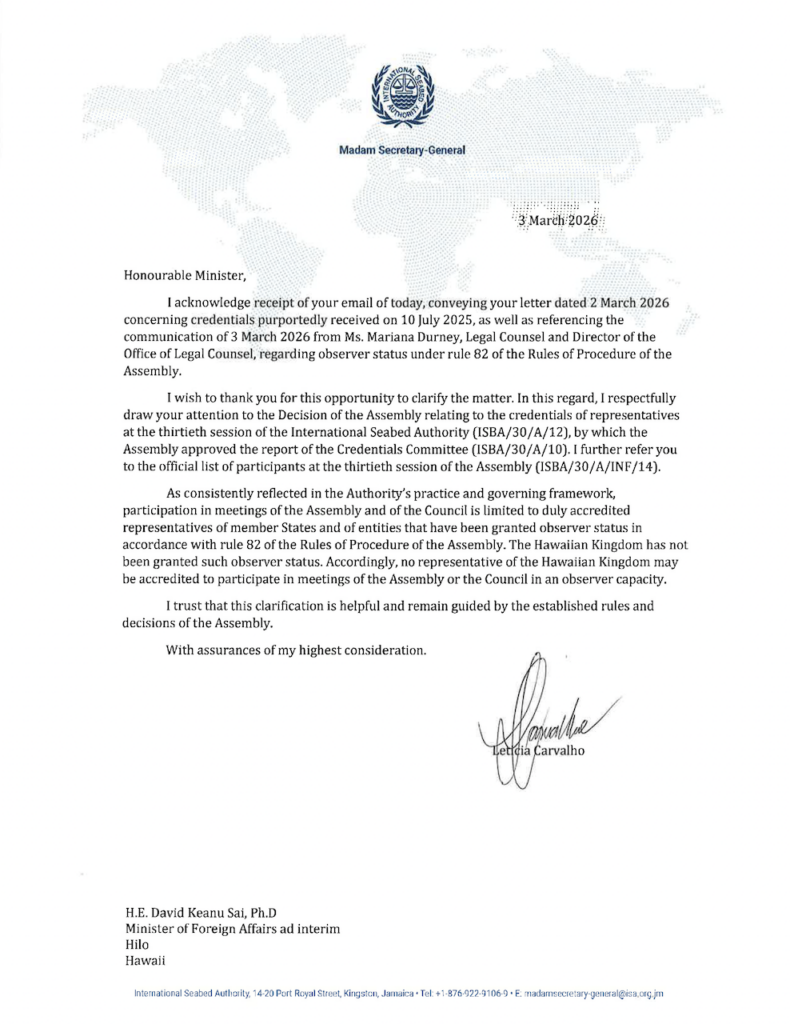

Later that day of the same date, Minister Dr. Sai received an email, with an enclosed “formal letter,” from Secretary General Carvalho clarifying the rules and practice for a State to participate in meetings of the ISA as an observer.

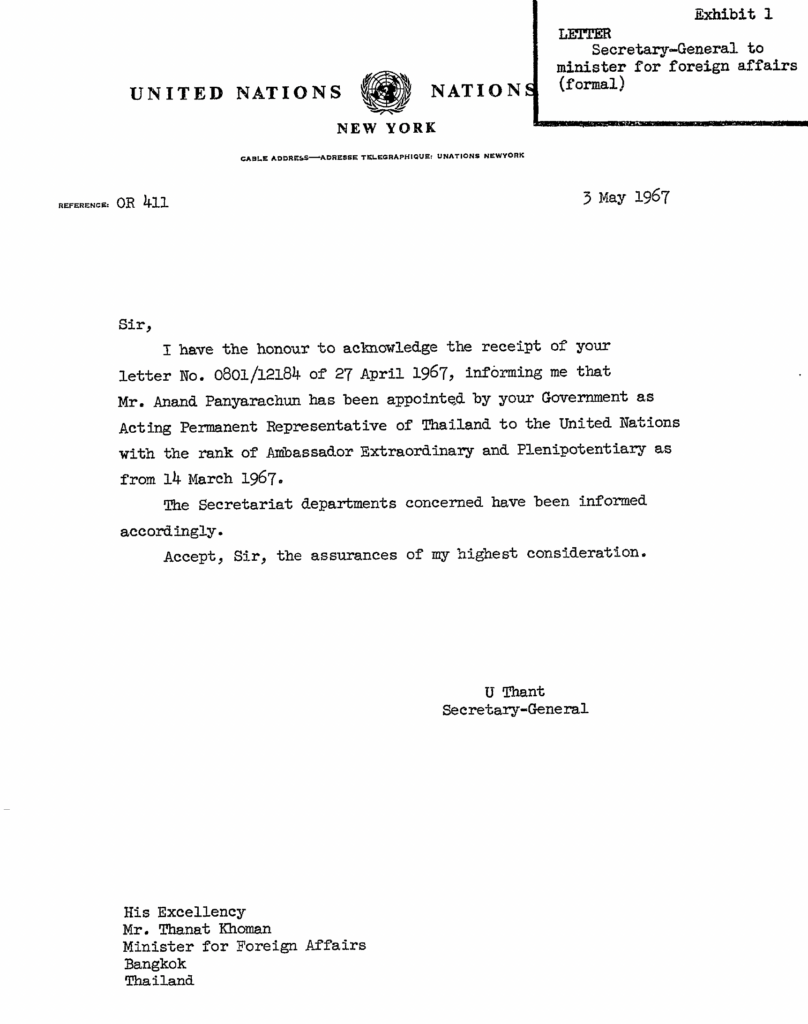

According to the United Nations Correspondence Manual, “Formal letters are those employing diplomatic style and phraseology. Normally such letters are addressed only to heads of State or heads of Government, ministers for foreign affairs and [Ambassadors].” And that “Formal letters to ministers for foreign affairs […] should, as a rule, include the name of the addressee in the address. The address should also contain full personal titles such “His Excellency.” Here is an example of a formal letter from the Secretary General of United Nations to a Minister of Foreign Affairs.

In her formal letter to Minister Dr. Sai, Secretary General Carvalho stated:

On March 5, 2026, Minister Dr. Sai acknowledged receipt of Secretary General Carvalho’s communication, dated March 3, 2026. In his letter to the Secretary General, Minster Dr. Sai stated:

Excellency:

This letter acknowledges your email, of 3 March 2026, which enclosed your letter of the same date, and the email from Ms. Mariana Durney, Legal Counsel and Director of the Office of Legal Counsel, of 3 March 2026, which enclosed her letter of the same date. I wish to thank you for Your Excellency’s recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State, under customary international law, since the nineteenth century, despite the prolonged nature of the belligerent occupation, by the United States of America, that began on 17 January 1893.

The International Seabed Authority’s recognition is consistent with the recognitions of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the Permanent Court of Arbitration during arbitral proceedings in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom from 1999 to 2001, by the United States’ recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom under the 2000 Sai-Clinton agreement, a treaty under international law, and by the 127 Contracting States to the 1907 Hague Convention, I, for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes that established the Permanent Court, under opinio juris.

Of the 169 Member States of the International Seabed Authority, 111 of these States are also Member States of the Permanent Court, to wit: Albania, Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belgium, Belize, Benin, Bolivia (Plurinational State of), Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Canada, Chile, China, Congo, Costa Rica, Croatia, Cuba, Cyprus, Czechia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Denmark, Djibouti, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Estonia, Eswatini, Fiji, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Hungary, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Kuwait, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Latvia, Lebanon, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Madagascar, Malaysia, Malta, Mauritius, Mexico, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Nigeria, North, Macedonia, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Qatar, Republic of Korea, Romania, Russian Federation, Rwanda, Sao Tome and Principe, Saudi Arabia, Senegal, Serbia, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, State of Palestine, Sudan, Suriname, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Togo, Uganda, Ukraine, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Uruguay, Vanuatu, Viet Nam, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. And there are 15 Observer States that are also Member States of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, to wit: Cambodia, Colombia, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Israel, Kyrgyzstan, Libya, Liechtenstein, Peru, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United States of America, and Venezuela.

My communication of 28 July 2025 to Ms. Durney, provided her the factual and legal basis of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as a State, under customary international law, and the restoration of the government by a Council of Regency under Hawaiian constitutional law and the legal doctrine of necessity, so that it can pursue Observer State status under rule 82 of the Rules of Procedure of the Assembly of the International Seabed Authority.

I wish to thank you for your clarification of the rules and practices of the International Seabed Authority regarding observer status. The Hawaiian Kingdom intends to pursue its observer status accordingly so that its Special Envoy can be accredited to participate in meetings of the Assembly or the Council under Rule 82 of the Rules of Procedure of the Assembly.

Please accept, Excellency, the expression of my highest consideration.

[signed]

H.E. David Keanu Sai, Ph.D.

Minister of Foreign Affairs ad interim

Her Excellency Letitia Carvalho

Secretary General of the International Seabed Authority

14-20 Port Royal Street

Kingston, Jamaica

“The recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as a State under international law by the Secretary General of the International Seabed Authority is a significant act taken by a reputable international body represented by 171 countries,” stated Minister Dr. Sai. He explained, “The Hawaiian Kingdom took deliberate steps to become accredited as an Observer State so that it can participate in meetings of the International Seabed Authority, because its fisheries and marine environment in its 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone has been unlawfully exploited by the United States for over a century.”

Minister Dr. Sai also stated, “The Hawaiian Kingdom will now proceed toward securing Observer State status so that its Special Envoy can participate in the meetings of the Council and the Assembly of the ISA in the very near future.”

MEDIA CONTACT:

Dr. David “Keanu” Sai, Ph.D.

Chairman of the Council of Regency

Acting Minister of the Interior

Acting Minister of Foreign Affairs ad interim

Email: interior@hawaiiankingdom.org