The Council of Regency, serving as the provisional government of the Hawaiian Kingdom, was established within Hawaiian territory—in situ, and not in exile. The Hawaiian government was established in accordance with the Hawaiian constitution and the doctrine of necessity to serve in the absence of the office of Executive Monarch. Queen Lili‘uokalani was the last Executive Monarch from 1891-1917.

By virtue of this process the Hawaiian government is comprised of officers de facto. According to U.S. constitutional scholar Thomas Cooley:

A provisional government is supposed to be a government de facto for the time being; a government that in some emergency is set up to preserve order; to continue the relations of the people it acts for with foreign nations until there shall be time and opportunity for the creation of a permanent government. It is not in general supposed to have any authority beyond that of a mere temporary nature resulting from some great necessity, and its authority is limited to the necessity.

During the Second World War, like other governments formed during foreign occupations of their territory, the Hawaiian government did not receive its mandate from the Hawaiian legislature, but rather by virtue of Hawaiian constitutional law as it applies to the Cabinet Council, which is comprised of the constitutional offices of the Minister of Interior, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Finance and the Attorney General.

Although Article 33 of the 1864 Constitution, as amended, provides that the Cabinet Council “shall be a Council of Regency, until the Legislative Assembly, which shall be called immediately [and] shall proceed to choose by ballot, a Regent or Council of Regency, who shall administer the Government in the name of the King, and exercise all the Powers which are constitutionally vested in the King,” the convening of the Legislative Assembly was not possible in light of the prolonged occupation. The impossibility of convening the Legislative Assembly during the occupation did not prevent the Cabinet from becoming the Council of Regency because of the operative words “shall be a Council of Regency, until…,” but only prevents, for the time being of occupation, the Legislature from electing a Regency or Regency. That election will take place when the occupation comes to an end.

Therefore, the Council was established in similar fashion to the Belgian Council of Regency after King Leopold was captured by the Germans during the Second World War. As the Belgian Council was established under Article 82 of its 1821 Constitution, as amended, in exile, the Hawaiian Council was established under Article 33 of its 1864 Constitution, as amended, not in exile but rather in situ. As Professor Oppenheim explained:

As far as Belgium is concerned, the capture of the king did not create any serious constitutional problems. According to Article 82 of the Constitution of February 7, 1821, as amended, the cabinet of ministers have to assume supreme executive power if the King is unable to govern. True, the ministers are bound to convene the House of Representatives and the Senate and to leave it to the decision of the united legislative chambers to provide for a regency; but in view of the belligerent occupation it is impossible for the two houses to function. While this emergency obtains, the powers of the King are vested in the Belgian Prime Minister and the other members of the cabinet.

The existence of the restored government in situ was not dependent upon diplomatic recognition by foreign States, but rather operated on the presumption of recognition these foreign States already afforded to the Hawaiian government as of 1893.

The recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State on November 28, 1843, was also the recognition of its government—a constitutional monarchy, as its agent. Successors in office to King Kamehameha III, who at the time of international recognition was King of the Hawaiian Kingdom, did not require diplomatic recognition. These successors included King Kamehameha IV in 1854, King Kamehameha V in 1863, King Lunalilo in 1873, King Kalākaua in 1874, and Queen Lili‘uokalani in 1891. The legal doctrines of recognition of new governments only arise “with extra-legal changes in government” of an existing State. Successors to King Kamehameha III were not established through “extra-legal changes,” but rather under the constitution and laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. According to Professor Peterson:

A government succeeding to power according to the constitution, basic law, or established domestic custom is assumed to succeed as well to its predecessor’s status as international agent of the state. Only if there is legal discontinuity at the domestic level because a new government comes to power in some other way, as by coup d’état or revolution, is its status as an international agent of the state open to question.

The Hawaiian Council of Regency is a government restored in accordance with the constitutional laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom as they existed prior to the unlawful overthrow of the previous administration of Queen Lili‘uokalani. It was not established through “extra-legal changes,” and, therefore, did not require diplomatic recognition to give itself validity as a government. It was a successor in office to Queen Lili‘uokalani as the Executive Monarch.

According to Professor Lenzerini in his legal opinion, based on the doctrine of necessity, “the Council of Regency possesses the constitutional authority to temporarily exercise the Royal powers of the Hawaiian Kingdom.” He also concluded that the Regency “has the authority to represent the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State, which has been under a belligerent occupation by the United States of America since 17 January 1893, both at the domestic and international level.”

After all four offices of the Cabinet Council were filled on September 26, 1999, a strategic plan was adopted based on its policy: first, exposure of the prolonged occupation; second, ensure that the United States complies with international humanitarian law; and, third, prepare for an effective transition to a completely functioning government when the occupation comes to end. The Council of Regency’s strategic plan has three phases to carry out its policy.

Phase I: Verification of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State and subject of International Law

Phase II: Exposure of Hawaiian Statehood within the framework of international law and the laws of occupation as it affects the realm of politics and economics at both the international and domestic levels.

Phase III: Restoration of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State and a subject of International Law, which is when the occupation comes to an end.

This Grand Strategy of the Council of Regency is long term, not short term, and can be compared to China’s Grand Strategy, which is also long term. As Professors Flynt Leverett and Wu Bingbing explain in their article The New Silk Road and China’s Evolving Grand Strategy:

What is grand strategy, and what does it mean for China? In broad terms, grand strategy is the culturally shaped intellectual architecture that structures a nation’s foreign policy over time. It is, in Barry Posen’s aphoristic rendering, “a state’s theory of how it can best ‘cause’ security for itself.” Put more functionally, grand strategy is a given political order’s template for marshalling all elements of national power to achieve its self-defined long-term goals. Diplomacy—a state’s capacity to increase the number of states ready to cooperate with it and to decrease its actual and potential adversaries—is as essential to grand strategy as raw military might. So too is economic power. For any state, the most basic goal of grand strategy is to protect that state’s territorial and political integrity. Beyond this, the grand strategies of important states typically aim to improve their relative positions by enhancing their ability to shape strategic outcomes, maximize their influence, and bolster their long-term economic prospect.

Phase I was completed when the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) acknowledged the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State for the purposes of its institutional jurisdiction under Article 47 of the 1907 Hague Convention, I, for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes prior to forming the arbitration tribunal on June 9, 2000. This acknowledgment of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State can be found at its case repository for Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom and on its website. The non-participation of the United States in the arbitration proceedings occurred “after” the PCA already acknowledged the continued existence of Hawaiian Kingdom Statehood.

On the day when the arbitration tribunal was formed, Phase II was initiated—exposure. Phase II would be guided by Section 495—Remedies of Injured Belligerent, United States Army FM 27-10, which states, “In the event of violation of the law of war, the injured party may legally resort to remedial action of…Publication of the facts, with a view to influencing public opinion against the offending belligerent.” The exposure began with the filings of the Hawaiian Kingdom in the arbitration proceedings and its oral arguments on December 8 and 11, 2000, at the PCA, in The Hague, Netherlands, which can be seen in this mini-documentary of the proceedings.

After the last day of the Larsen hearings were held at the PCA on December 11, 2000, the Council was called to an urgent meeting by Dr. Jacques Bihozagara, Ambassador for the Republic of Rwanda assigned to Belgium. Ambassador Bihozagara had been attending a hearing before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on December 8, Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Belgium, where he became aware of the Hawaiian arbitration case taking place in the hearing room of the PCA across the hall of the Peace Palace. Both the PCA and the ICJ are housed in the same building.

The following day, the Council, which included David Keanu Sai, acting Minister of Interior and Chairman of the Council of Regency, as Agent, and two Deputy Agents, Peter Umialiloa Sai, acting Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Mrs. Kau‘i P. Sai-Dudoit, formerly known as Kau‘i P. Goodhue, acting Minister of Finance, met with Ambassador Bihozagara in Brussels. In that meeting, the Ambassador explained that since he accessed the pleadings and records of the Larsen case on December 8 from the PCA’s Secretariat, he had been in communication with his government in Kigali. This prompted our meeting where the Ambassador conveyed to the Council that his government was prepared to bring to the attention of the United Nations General Assembly the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States and to place our situation on the agenda. The Council requested a short break from the meeting to discuss this offer.

After careful deliberation, the Council of Regency decided that it could not, in good conscience, accept this offer. The Council felt that the timing was premature because Hawai‘i’s population remained ignorant of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s profound legal position due to institutionalized denationalization through Americanization by the United States for over a century. The Council graciously thanked the Ambassador for his government’s offer but stated that the Council first needed to address over a century of denationalization. After exchanging salutations, the meeting ended, and the Council returned that afternoon to The Hague. The meeting also constituted recognition of the restored government.

Since the Council of Regency returned home from the Netherlands, it was agreed that David Keanu Sai would enter the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa to pursue a Masters Degree in Political Science, specializing in international relations and law, and then a Ph.D. Degree in Political Science with particular focus on the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State. Dr. Sai is currently a Lecturer in Political Science and Hawaiian Studies at the University of Hawai‘i Windward Community College and Affiliate Faculty of the Graduate Division of the University of Hawai‘i College of Education.

Kau‘i Sai-Dudoit would work for the Hawaiian newspaper project and she is currently Programs Director for Awaiaulu, Inc. Awaiaulu is dedicated to developing resources and resource people that can bridge Hawaiian knowledge from the past to the present and the future. Historical resources are made accessible so as to build the knowledge base of both Hawaiian and English-speaking audiences, and young scholars are trained to understand and interpret those resources for modern audiences today and tomorrow.

Since Phase II of Exposure began:

- Multiple Master’s theses, Ph.D. dissertations, published articles and books address different subjects in the Hawaiian Kingdom as an occupied State.

- Classes are now being taught here and abroad on the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its prolonged occupation by the United States.

- On July 12, 2002, Professor Matthew Craven author’s Legal Opinion on the Continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under International Law.

- 2011, Dr. Keanu Sai author’s book Ua Mau Ke Ea – Sovereignty Endures: An Overview of the Political and Legal History of the Hawaiian Islands.

- The Hawai‘i State Teachers Association, representing public school teachers throughout Hawai‘i, introduced a resolution at the National Education Association’s (NEA) annual assembly in Boston, Massachusetts, which passed on July 4, 2017, that called upon the NEA to publish articles on the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy in 1893, the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom by the United States, and the harmful affects the occupation has had on the Hawaiian people and the resources of the land.

- On April 2, 2018, the NEA published the online article The Illegal Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom Government.

- On October 1, 2018, the NEA published the online article The U.S. Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

- On October 13, 2018, the NEA published the online article The Impact of the U.S. Occupation on the Hawaiian People.

- Attorneys continue to make legal arguments on the Hawaiian Kingdom’s existence in criminal and civil proceedings in State of Hawai‘i Courts.

- On February 25, 2018, Dr. Alfred deZayas, as the United Nations Independent Expert for the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva, Switzerland, sent a letter of communication to the State of Hawai‘i Judiciary regarding the prolonged occupation.

- On June 25, 2018, the Hawaiian Kingdom filed a Petition for Writ of Mandamus against President Donald Trump in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia in Washington, D.C.

- On July 25, 2019, Professor William Schabas author’s a Legal Opinion on War Crimes Related to the United States Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom since 17 January 1893.

- On October 4, 2019, Professor Federico Lenzerini author’s Legal Opinion—International Human Rights Law and Self-Determination of Peoples Related to the United States Occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom since 17 January 1893.

- After the National Lawyers Guild’s (NLG) membership passed a resolution in December of 2019, the National Office took an official position on January 13, 2020, Calling Upon US to Immediately Comply with International Humanitarian Law in its Illegal Occupation of the Hawaiian Islands.

- 2020 Dr. Keanu Sai (ed.) author’s Royal Commission of Inquiry: Investigating War Crimes and Human Rights Violations in the Hawaiian Kingdom, with contributing authors: Professor Matthew Craven, Professor William Schabas and Professor Federico Lenzerini.

- On November 10, 2020, the NLG sent a letter of communication to State of Hawai‘i Governor urging him to comply with international humanitarian law by transforming the State of Hawai‘i into an occupying government in order to administer Hawaiian Kingdom law and the law of occupation.

- On May 24, 2020, Professor Federico Lenzerini author’s a Legal Opinion on the Authority of the Council of Regency of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

- On February 7, 2021, the International Association of Democratic Lawyers (IADL) passed a resolution calling upon the United States to begin to comply with international humanitarian law in its prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

- On May 20, 2021, the Hawaiian Kingdom filed a Complaint against President Biden and other officials of the Federal Government and the State of Hawai‘i, which included 30 foreign Consulates operating in the Hawaiian Islands, Hawaiian Kingdom v. Biden et al., in the United States District Court for the District of Hawai‘i.

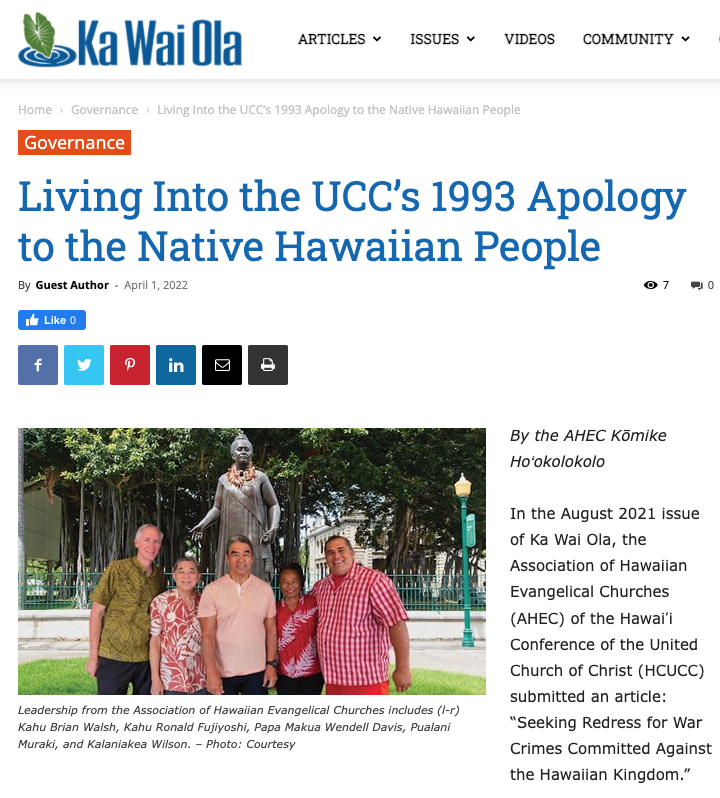

- On July 18, 2021, the General Synod of the United Church of Christ passed a resolution submitted by the Association of Hawaiian Evangelical Churches (AHEC), Encouraging to End 128 years of of War between the United States of America and the Hawaiian Kingdom.

- On August 11, 2021, the Hawaiian Kingdom filed an Amended Complaint in the United States District Court for the District of Hawai‘i by removing the Counties of the State of Hawai‘i as Defendants.

- After receiving permission from the Court in Hawaiian Kingdom v. Biden, on September 30, 2021, the IADL, the NLG and the Water Protector Legal Collective filed an Amicus Brief on the status of the Court as an Article II Occupation Court on October 6, 2021.

- On February 16, 2022, the IADL and the American Association of Jurists—Asociación Americana de Juristas (AAJ), both of whom have consultative status with the United Nations Human Rights Council, sent a joint letter to all United Nations Ambassadors calling for enforcement of international law regarding the prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

- The NLG, the IADL, the AAJ and AHEC support the Council of Regency and its strategy to bring the United States and the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties in compliance with international humanitarian law and the law of occupation.

- On February 23, 2022, AHEC sent a letter of communication to State of Hawai‘i Governor supporting the letter sent by the NLG on November 10, 2020, calling upon the State of Hawai‘i to transform into an Occupying Government.

- On March 22, 2022, Dr. Keanu Sai, as Minister of Foreign Affairs ad interim, delivered an opening statement to the United Nations Human Rights Council on behalf of the IADL and the AAJ apprising the Council of the United States prolonged occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the commission of war crimes through the unlawful imposition of American laws over Hawaiian territory.

In a documentary film on the Council of Regency, Donovan Preza, an Instructor at the University of Hawai‘i Kapi‘olani Community College stated:

Keanu was a boxer. He attended New Mexico [Military Institute] on a boxing scholarship so this is where I like to use this metaphor. Keanu has been brilliant about if the ring is this big-this is the boxing ring-when you’re standing here and America is standing there you’re not going to punch, you’re not going to land your knockout punch from across the ring. And America has been evading, dancing and sidestepping, not answering the question. You bring anything up in an American court and the political strategy used by the court is to make it a political question. Political question, the courts don’t have to answer it. So they kept dancing around not answering the question and Hawai‘i has never gotten close enough to force them to answer the question. And that’s what Keanu and the acting Council of Regency has been doing is systematically making that ring smaller, and smaller, and smaller, day by day, step by step, inch by inch. Everybody wants the ring to be this small now but small steps, increments, they’ve been doing that incrementally. If you’ve been paying attention to what they’ve been doing they have been making the ring smaller. Everybody wants to watch the knockout punch. Have some patience. Watch the ring get smaller until America has to answer the question. When they have to answer the question that’s when you can knock them out.

In the latest filings in Hawaiian Kingdom v. Biden et al., the Hawaiian Kingdom delivered the “knockout punch.” Judge Leslie Kobayashi was forced to answer the question of whether the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as a State under international law was extinguished by the United States. Because of the international rule of the presumption of continuity of a State despite the overthrow of its government, the question was not whether the Hawaiian Kingdom “does” continue to exist but rather can Judge Kobayashi state with evidence that the Hawaiian Kingdom “does not” continue to exist.

Under international law, according to Judge James Crawford, there “is a presumption that the State continues to exist, with its rights and obligations despite a period in which there is no effective, government,” and that belligerent “occupation does not affect the continuity of the State, even where there exists no government claiming to represent the occupied State.”

As Professor Matthew Craven explains, “If one were to speak about a presumption of continuity, one would suppose that an obligation would lie upon the party opposing that continuity to establish the facts sustaining its rebuttal. The continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom, in other words, may be refuted only by reference to a valid demonstration of legal rights, or sovereignty, on the part of the United States, absent of which the presumption remains.” According to Craven, only by the Hawaiian Kingdom’s “incorporation, union, or submission” to the United States, which is by treaty, can the presumption of continuity be rebutted.

After eleven months of these court proceedings, the Hawaiian Kingdom was finally able to corner Judge Kobayashi to legally compel her to answer the question of extinguishment after she made it an issue in her Order of March 30, 2022 and Order of March 31, 2022. In these two Orders, Judge Kobayashi made the terse statement “there is no factual (or legal basis) for concluding that the [Hawaiian] Kingdom exists as a state in accordance with recognized attributes of a state’s sovereign nature.” This statement runs counter to international law where an international rule exists regarding the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State despite the United States admitted illegal overthrow of its government on January 17, 1893. She provided no evidence to back up her one line statement in these Orders but she did, however, open the door for the Hawaiian Kingdom to respond.

The Hawaiian Kingdom responded with a Motion for Reconsideration filed on April 11, 2022, that legally compelled Judge Kobayashi to provide a “valid demonstration of legal rights, or sovereignty, on the part of the United States, absent of which the presumption remains.” In her Order of April 19, 2022, denying the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Motion for Reconsideration, Judge Kobayashi provided no “valid demonstration of legal rights, or sovereignty, on the part of the United States.” She simply stated, “Although Plaintiff argues there are manifest errors of law in the 3/30/22 Order and the 3/31/22 Order, Plaintiff merely disagrees with the Court’s decision.” This statement without any evidence is not a rebuttal of the presumption of the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

As a United States District Court Judge, by not providing any evidence in these proceedings that the Hawaiian Kingdom was extinguished, she simultaneously acknowledged its continued existence. This is the power of the international rule of the presumption of continuity that operates no different than the presumption of innocence in a criminal trial. Just as a defendant does not have the burden to prove his/her innocence but rather the prosecution has the burden to prove with evidence the guilt of the defendant, the Hawaiian Kingdom does not have the burden to prove its continued existence but rather the opposing party has the burden to prove with evidence that the United States extinguished the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under international law.

These federal proceedings have now come to a close and the records have been preserved when the Hawaiian Kingdom filed a Notice of Appeal on April 24, 2022, to be taken up by an Article II Occupation Court of Appeals that has yet to be established by the United States. By preserving the record, the Hawaiian Kingdom can utilize Judge Kobayashi’s statements against the United States and the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties.