The federal courts of the United States represent a higher level of standard than courts within the various States of the American Union. What is at its core is the “rule of law” that provides legal predictability, continuity, and coherence; reasoned decisions made through publicly visible processes and based faithfully on the law. U.S. District Courts, unlike the Appellate Courts, have trials that apply the rule of law in filings, proceedings and evidence. You don’t have trials at the Appellate Court.

Rule 11(b) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure addresses representations to the Court. “By presenting to the court a pleading, written motion, or other paper…an attorney…certifies that to the best of the person’s knowledge, information, and belief, formed after an inquiry reasonable under the circumstances: (1) it is not being presented for any improper purpose, such as to harass, cause unnecessary delay, or needlessly increase the cost of litigation; (2) the claims, defenses, and other legal contentions are warranted by existing law or by a nonfrivolous argument for extending, modifying, or reversing existing law or for establishing new law; (3) the factual contentions have evidentiary support or, if specifically so identified, will likely have evidentiary support after a reasonable opportunity for further investigation or discovery; and (4) the denials of factual contentions are warranted on the evidence or, if specifically so identified, are reasonably based on belief or a lack of information.”

If an attorney files any written motion that violates these conditions, he/she can be sanctioned by the Court under Rule 11(c)(1), which states, “If, after notice and a reasonable opportunity to respond, the court determines that Rule 11(b) has been violated, the court may impose an appropriate sanction on any attorney, law firm, or party that violated the rule or is responsible for the violation. Absent exceptional circumstances, a law firm must be held jointly responsible for a violation committed by its partner, associate, or employee.” In other words, if a motion is frivolous, the attorney can be sanctioned.

The basis of this rule would also apply to Declarations made in support of a motion where the declarant would have committed the crime of perjury if what was stated in the Declaration are false statements. This comes under U.S. Federal law 18 U.S.C. §1621 and §1623. This is why in Declarations filed with Federal Courts it states, “I declare under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is true and correct to the best of my knowledge.”

Rule 11(b)(2) applies to the content of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Motion for Reconsideration, which is “warranted by existing law.” In the District Courts, along with constitutional provisions and statutes, existing law includes Federal Court decisions that came before the Appellate Courts or the Supreme Court.

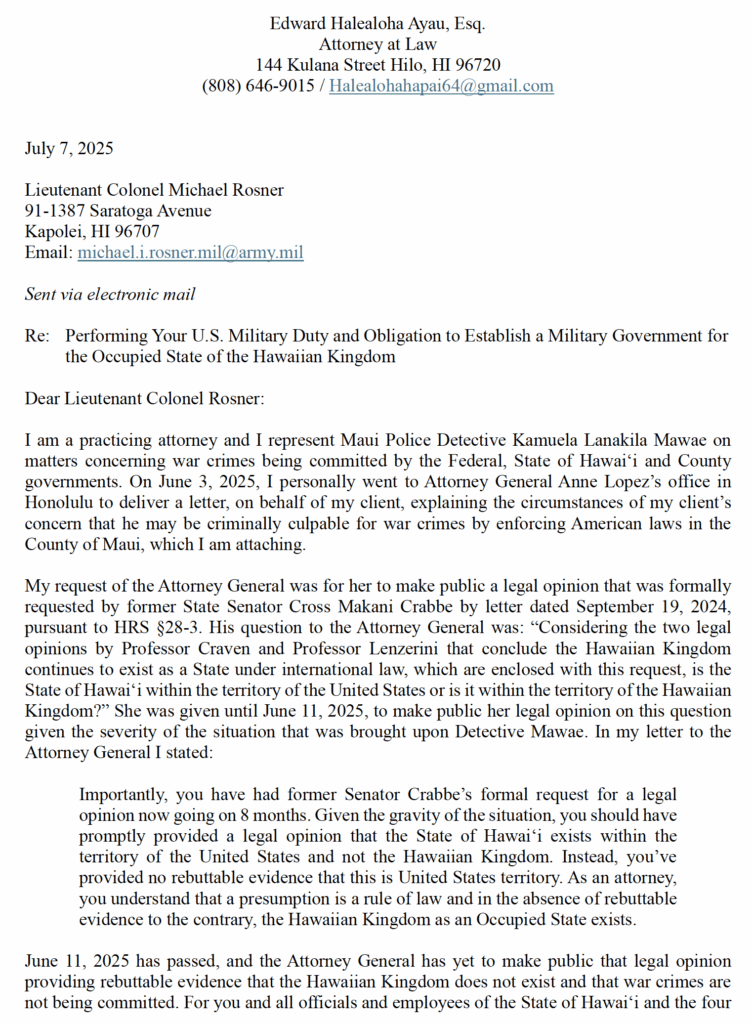

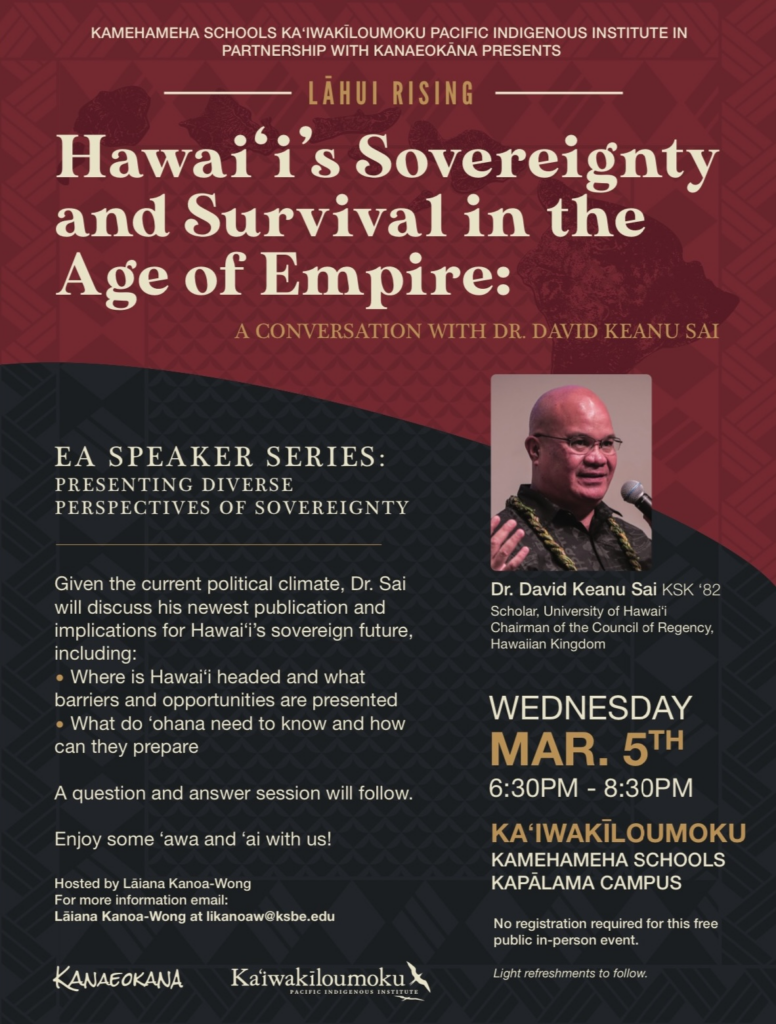

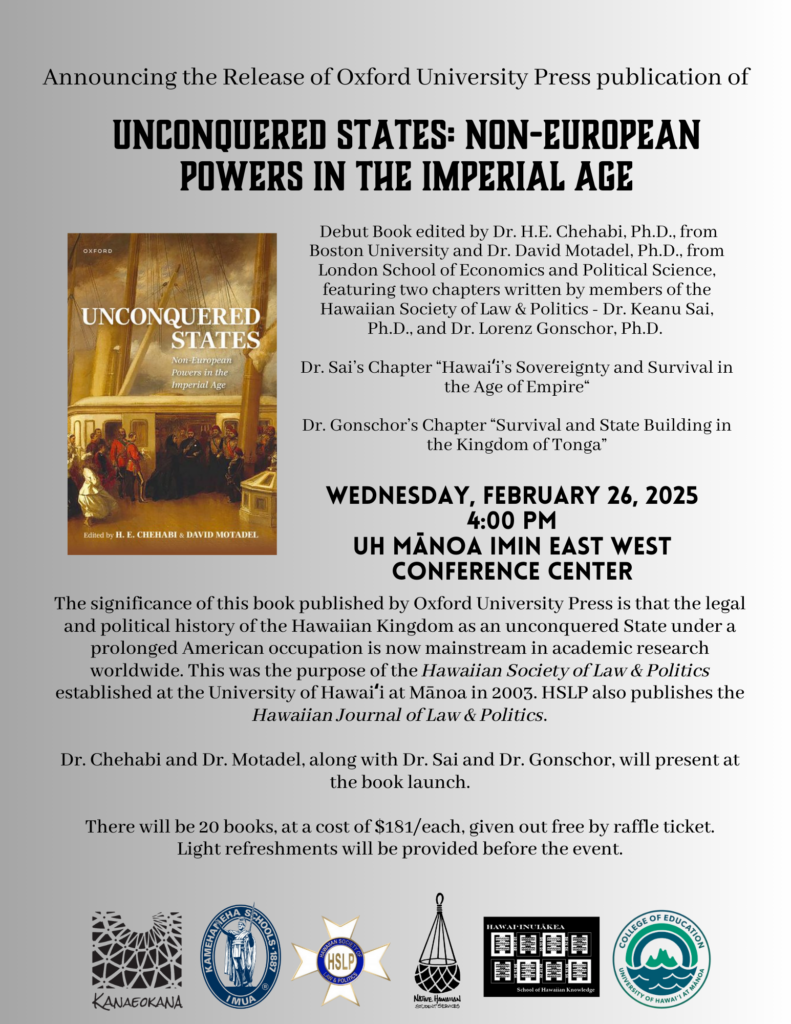

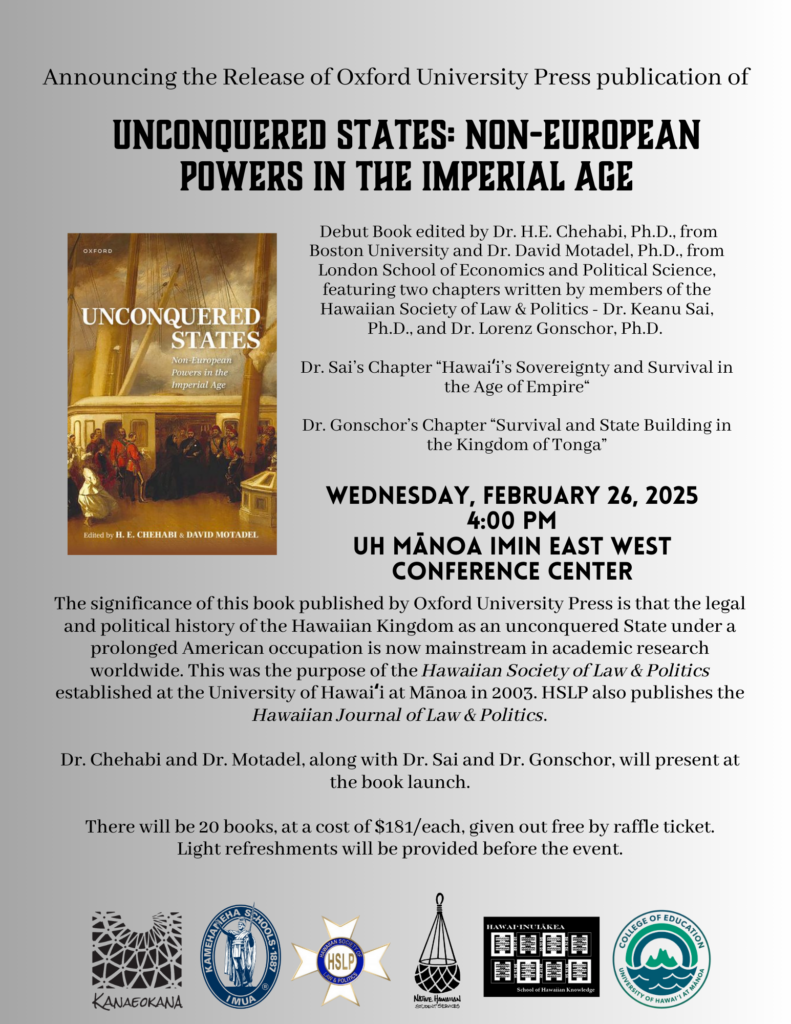

In the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Motion for Reconsideration, it provided clear evidence of two instances that the United States recognized the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the Council of Regency as its government while administrative proceedings took place at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Netherlands, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom (1999-2001).

The first instance was by executive agreement between the Council of Regency and the United States, by its Embassy in the Netherlands, that provided permission to the United States to access all records and pleadings of the case. Under international law, this is called an executive agreement, by exchange of notes. Pertinent Supreme Court decisions on this subject of executive agreements that were cited in the Motion for Reconsideration are United States v. Belmont (1937), United States v. Pink (1942), and American Ins. Ass’n v. Garamendi (2003).

In Garamendi, the Supreme Court stated, “our cases have recognized that the President has authority to make ‘executive agreements’ with other countries, requiring no ratification by the Senate […] this power having been exercised since the early years of the Republic.”

In Belmont, the Supreme Court stated, “an international compact […] is not always a treaty which requires the participation of the Senate.”

And in Pink, the Supreme Court stated, “all international compacts and agreements’ are to be treated with similar dignity, for the reason that ‘complete power over international affairs is in the national government, and is not and cannot be subject to any curtailment or interference on the part of the several states.”

The significance on the executive agreement between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States is stated by the Supreme Court in Garamendi where, “valid executive agreements are fit to preempt state law, just as treaties are.” In other words, the executive agreement negates the legal existence of the State of Hawai‘i, and the consequences of this executive agreement where the United States recognizes the continued existence of the sovereignty of the Hawaiian Kingdom over the Hawaiian Islands is clearly stated by the Supreme Court in Jones v. United States (1890). In Jones, the Supreme Court stated:

By the constitution of the United States, the President is invested with certain important political powers, in the exercise of which he is to use his own discretion, and is accountable only to his country in his political character, and to his own conscience. […] He is the mere organ by whom that will is communicated. The acts of such an officer, as an officer, can never be examinable by the courts.”

In Jones, the Supreme Court also stated that recognition of the sovereignty of a State “conclusively binds the judges, as well as all other officers, citizens, and subjects of that government.” In other words, this executive agreement of recognition binds District Court Judge Micah Smith, the Plaintiffs Student for Fair Admission and the Defendant Kamehameha Schools and that it “can never be examinable by the courts” of the United States, which includes State courts.

The Court, together with the Plaintiffs and the Defendant, are not the contracting parties to the executive agreement, but are bound not to question or examine it, unless they can provide evidence that there is no such executive agreement ever made. To do so, however, is to have the United States Attorney General intervene in the case and provide evidence that there is no such thing as an executive agreement between the Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States, a claim that would be considered frivolous under Rule 11(b). Therefore, the U.S. Attorney General, after intervening in the lawsuit, will have to counter the evidential basis of the executive agreement in the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Motion for Reconsideration. As a contracting party to the executive agreement, only the United States can examine the evidence of the executive agreement.

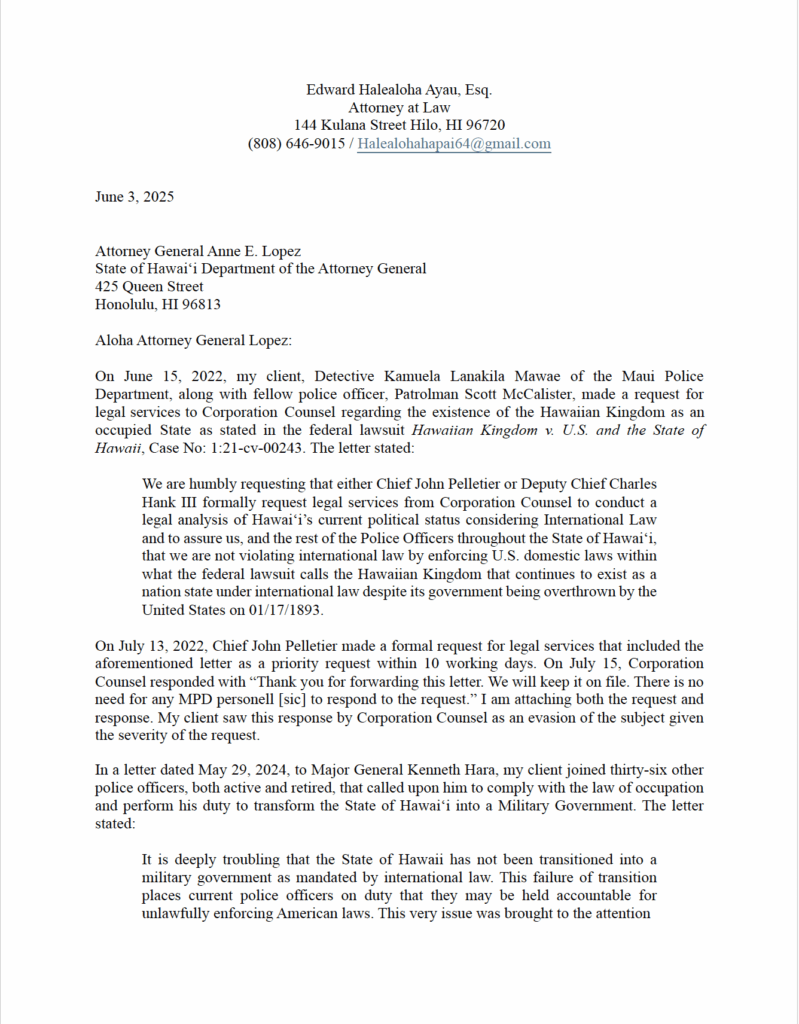

The second instance was by opio juris—customary international law where none of the Contracting States to the treaty that formed the Permanent Court, to include the United States, did not object to the Permanent Court’s recognition of the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the Council of Regency as its government in order for it to have established the arbitration tribunal on June 9, 2000. This was explained in a legal opinion by Federico Lenzerini, a professor of international law at the University of Siena, Italy, which was Exhibit 1 attached to his Declaration that was filed with the Motion for Reconsideration.

The Supreme Court has recognized that the writings of legal scholars are a source of customary international law. In the Paquete Habana case (1900), the Supreme Court stated, “the works of jurists and commentators, who by years of labor, research and experience, have made themselves peculiarly well acquainted with the subjects they treat. Such works are resorted to by judicial tribunals, not for the speculations of their authors concerning what the law ought to be, but for trustworthy evidence of what the law really is.”

These scholars also include Professor Matthew Craven’s legal opinion on the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under international law, which is Exhibit B attached to the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Motion to Intervene; Professor Federico Lenzerini’s legal opinion on the authority of the Council of Regency of the Hawaiian Kingdom attached as Exhibit D to the Motion to Intervene; and Professor William Schabas’ legal opinion on war crimes related to the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom attached as Exhibit E to the Motion to Intervene.

As they say in the game of chess, checkmate, which is where there is no possible escape for the United States.