To mention white supremacy in the Hawaiian Islands for some is a bit strange because it does not appear that white people are in control. Their control, however, was cemented after the United States illegally overthrew the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893. This control lasted until 1959, where former laborers in the sugar and pineapple plantations, after returning from the Second World War, seized political control and pushed for the Hawaiian Islands to be the 50th State of the American Union where the governor would now be an elected position.

The leadership of the insurgency, calling themselves the provisional government, were white, which included Sanford Dole, William O. Smith and Lorrin Thurston. These insurgents, while white by ethnicity, were Hawaiian subjects by nationality and not American citizens. From 1900 to 1959, the leadership of the so-called Territory of Hawai‘i was appointed by the President of the United States. There were only white governors during this period. As a State of Hawai‘i, the former plantation workers would control the voting bloc under American law.

As a minority of the population, the insurgents of 1893 aligned themselves with Americans to entice the United States to annex the Hawaiian Islands after the government was overthrown. By aligning themselves with American politics, they also aligned themselves with American culture—white supremacy. According to Tom Coffman in his book Nation Within—The History of the American Occupation of the Hawai‘i, the insurgents attended higher education in the United States and it is there that they learned what was not experienced in the Hawaiian Kingdom, which is the so-called supremacy of the white race.

Despite the insurgents’ propaganda of lies, their rhetoric, however, was fueled, at the time, by American politics of race relations and the superiority of the Aryan (Teutonic) race over all others. Coffman addresses this by asking what “had Lorrin Thurston learned at Columbia, and what had Sanford Dole learned from his journey up the Kennebec River?” He answered, “the missionary descendants—already so prepared to believe in the superiority of their knowledge and position—were being influenced by American culture and American public life to take over direct control of Hawai‘i.” Between 1840 and 1887, Coffman explains “a systemic theory of white supremacy had been developed that came to be described in the intellectual history of America as Social Darwinism. The keystone of Social Darwinism was the teaching of white supremacy.”

While their physical strength was miniscule in the Hawaiian Kingdom, their arrogance could not be underestimated. The officers of the Hawaiian Patriotic League, in a memorial to President Grover Cleveland dated December 27, 1893, succinctly explained:

Last January, a political crime was committed, not only against the legitimate Sovereign of the Hawaiian Kingdom, but also against the whole Hawaiian nation, a nation who, for the past sixty years, had enjoyed free and happy constitutional self-government. This was done by a coup de main of U.S. Minister Stevens, in collusion with a cabal of conspirators, mainly faithless sons of missionaries and local politicians angered by continuous political defeat, who, as a revenge for being a hopeless minority in the country, resolved to “rule or ruin” through foreign help.

After Cleveland failed to restore Queen Lili‘uokalani under an executive agreement of December 18, 1893, the insurgents became emboldened. Prior to changing the name of the insurgency from the provisional government to the Republic of Hawai‘i in 1894, this minority of people needed to stay in control until a new president entered office after President Cleveland. That President was William McKinley who was open to annexing the Hawaiian Islands.

Professor John Burgess, a political scientist at Columbia University in 1893, was an academic who openly subscribed to white superiority through “Teutonic supremacy in the art of government.” According to Burgess, Teutonic governance was exemplified by “northern Europe and the United States,” but the Hawaiian Kingdom government, led by aboriginal Hawaiians, was not included in this theory because the Polynesian race was not Teutonic. The insurgents, although being Hawaiian subjects and resident aliens, were representative of the so-called Teutonic race. According to Castle, Burgess firmly believed that the “exercise of political right was contingent upon innate political intelligence, and of this intelligence the Teutons were the only qualified judges.”

To the Hawaiian, Burgess’ belief of Teutonic political intelligence would be absurd because Hawai‘i’s constitutional monarchy predated that of Teutonic Prussia. As German political scientist Marquardt pointed out in 2009, “Hawai‘i as early as 1839, preceding even Prussia, transferred European constitutionalism, in the pattern of the constitutional monarchy, into the Austronesian-speaking world of Oceania.” Nevertheless, as facts were not the driving force, the situation was being driven by American racist rhetoric.

Knowing of Burgess’ agenda of promoting white, in particular, Teutonic—Aryan superiority in governance, Dole was in communication with Burgess a year after the overthrow of the Hawaiian government. He wanted to draft a constitution for the insurgency that would change its name from the provisional government to the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i on July 3, 1894. Concerned of the political power wielded by the aboriginal Hawaiian, which was the majority of the Hawaiian national population, the insurgents entertained Jim Crow laws from the American State of Mississippi. In a letter sent from Washington, D.C., on November 4, 1893, by W.D. Alexander, former Surveyor-General of the Hawaiian Kingdom, to Sanford Dole, he wrote, “I enclose extracts from the present Constitution of Mississippi, which is said to have the effect of disfranchising a majority of the negroes of that state.” The Republic of Hawai‘i was in name only. It was not, by definition, a true Republic where the affairs of government were open and transparent.

In his first letter, Dole was merely asking for clarity on a section of Burgess’ book Political Science and Comparative Constitutional Law. Before Burgess responded, Dole was able to send a follow up letter that reveals his intent. In his second letter, Dole requests information from Burgess on his constitutional plan whereby “government can be kept out of the control of the irresponsible element.” He stated that there “are many natives and Portuguese who had had the vote hitherto, who are comparatively ignorant of the principles of government, and whose vote from its numerical strength as well as from the ignorance referred to will be a menace to good government.” Burgess, in his response to Dole, was aware that the so-called Teutonic population in Hawai‘i was a very small minority at 5,000, which he said comprised of “Americans, English, Germans and Scandinavians” out of “a population of nearly 100,000.” After offering suggestions in the organizing of government, he ends his letter by recommending that “only Teutons [be appointed] to military office.”

When Coffman mentions the Dole-Burgess letters, he implies that the Hawaiian Kingdom did not have the same race relations as the United States. According to Dominguez, there was “very little overlap with Anglo-American” race relations. She found that there were no “institutional practices [that] promoted social, reproductive, or civic exclusivity on anything resembling racial terms before the American period.” In comparing the two countries she stated that unlike “the extensive differentiating and disempowering laws put in place throughout the nineteenth century in numerous parts of the U.S. mainland, no parallels—customary or legislated—seem to have existed in the [Hawaiian Kingdom].” Dominguez admits that with “all the recent, welcomed publishing flurry on the social construction of whiteness and blackness and the sociohistorical shaping of racial categories…, there are usually at best only hints of the possible—but very real—unthinkability of ‘race.’”

That very real “unthinkability of race” was the Hawaiian Kingdom. Kauai explains that the “multi-ethnic dimensions of the Hawaiian citizenry coupled by the strong voice and participation of the aboriginal population in government played a prominent role in constraining racial hierarchy and the emergence of a legal system that promoted white supremacy.”

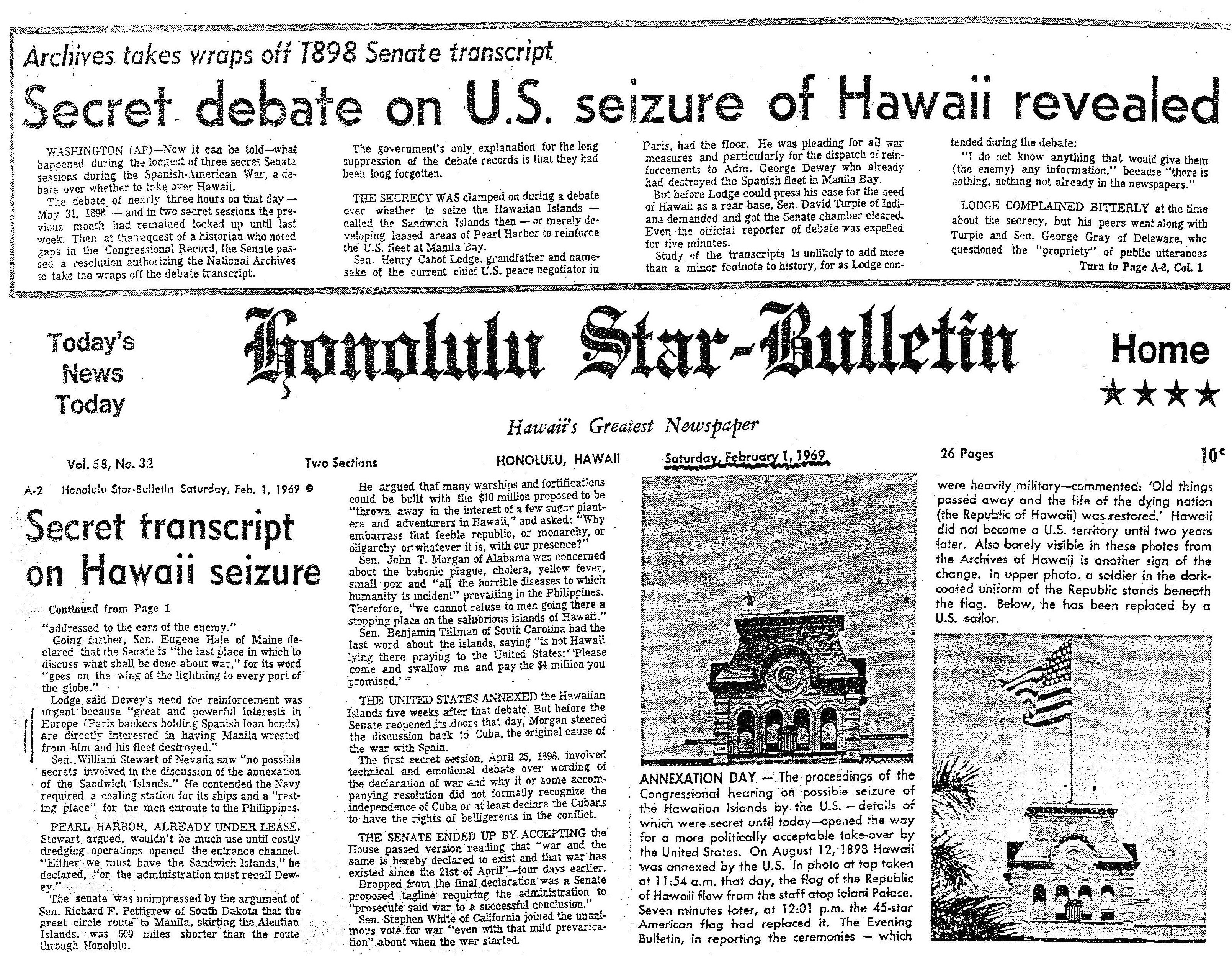

After unilaterally annexing the Hawaiian Islands by enacting an American law in the Congress called a joint resolution in 1898, and not by a treaty of cession, the denationalization through Americanization was firmly planted in the educational system throughout the Hawaiian Islands. To do this, the educational system established by the Hawaiian Kingdom would be weaponized. Thus began the brainwashing of the school children that obliterated the national consciousness of their country, the Hawaiian Kingdom, and imposed the English language over the Hawaiian language.

In 1919, the Allied Powers of the First World War concluded that “attempts to denationalize the inhabitants of occupied territory” is a war crime. In their report, the Allied Powers charged that Bulgaria imposed their national characteristics on the Serbian population; banned the Serbian language; people were beaten for saying “Good morning” in Serbian; and the Serbian population forced to be present at Bulgarian national ceremonies.

The United Nations War Crimes Commission established after the Second World War to prosecute war criminals stated:

Attempts of this nature were recognized as a war crime in view of the German policy in territories annexed by Germany in 1914”

At that time, as during the war of 1939-1945, inhabitants of an occupied territory were subjected to measures intended to deprive them of their national characteristics and to make the land and population affected a German province

Since 1898, the United States did exactly what Bulgaria and Germany did during the First and Second World Wars. Where the military occupations of the First and Second World Wars would only last 4 to 6 years, the policy of denationalization through Americanizatoin would last over a century unfettered. Within three generations, the national consciousness of the Hawaiian Kingdom was obliterated.

Under the ownership of the infamous insurgent Lorrin Thurston, the Pacific Commercial Advertiser newspaper served as the insurgents’ propaganda machine. In 1904, Walter G. Smith, an American from San Francisco, became its editor in chief. In the September 8, 1905, edition, he summed up the effect and purpose of weaponizing the educational system under the heading “The American Way.”

It would have been proper yesterday in the Advertiser’s discussion of schools to admit the success which the High School has had in making itself acceptable to white parents. By gradually raising the standard of knowledge of English the High School has so far changed its color that, during the past year seventy-three per cent. were Caucasians. It is not so many years ago that more than seventy-three per cent. were non-Caucasians. At the present rate of progress it will not be long before the High School will have its student body as thoroughly Americanized in blood as it long has been in instruction.

The idea of having mixed schools were the mixture is of various social and political conditions is wholly American; but not so mixed schools where the American youth is submerged by the youth of alien races. On the mainland the Polacks, the Russian Jews, the Huns and the negroes are, as far as practicable, kept in schools of their own, with the teaching in English; and only where the alien breeds are few, as in the country, are they permitted to mingle with white pupils. In the South, where Americans of the purest descent live, there are no mixed schools for whites and negroes; and wherever color or race is an issue of moment, the American way is defined through segregation. Only a few fanatics or vote-hunters care to lower the standard of the white child for the sake of raising that of the black or yellow child.

One great and potent duty of our higher schools, public and private, is to conserve the domination here of Anglo-Saxon ideas and institutions; and this means control by white men. We have no faith in any attempt to make Americans of Asiatics. There are too many obstacles of temperament and even of patriotism in the way. The main thing is to see that our white children when they grow up, are not to be differentiated from the typical Americans of the mainland, having the same standards, the same ideals and the same objects, none of them tempered by the creeds or customs of decaying or undeveloped or pagan races.

From a country, whose literacy rate was second to Scotland and New England, aboriginal Hawaiian school children were forced to enter the labor force after receiving an eighth grade education. If you were white, you were allowed to attend High School. In an article published by New York’s Harper’s Weekly magazine in 1907, the reporter, William Inglis, visited three schools that were established during the Kingdom – Ka‘iulani and Ka‘ahumanu public schools that went to the eighth grade, and Honolulu High School. At Kai‘iulani, he reported:

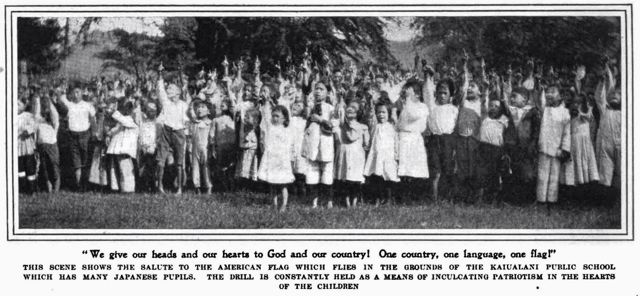

Out upon the lawn marched the children, two by two, just as precise and orderly as you can find them at home. With the ease that comes of long practice the classes marched and counter -marched until all were drawn up in a compact array facing a large American flag that was dancing in the northeast trade-wind forty feet above their heads. Surely this was the most curious, most diverse regiment ever drawn up under that banner – tiny Hawaiians, Americans, Britons, Germans, Portuguese, Scandinavians, Japanese, Chinese, Porto-Ricans, and Heaven knows what else.

“Attention!” Mrs. Fraser commanded.

The little regiment stood fast, arms at sides, shoulders back, chests out, heads up, and every eye fixed upon the red, white, and blue emblem that waved protectingly over them.

“Salute!” was the principal’s next command.

Every right hand was raised, forefinger extended, and the six hundred and fourteen fresh, childish voices chanted as one voice:

“We give our head and our hearts to God and our Country! One Country! One Language! One Flag!”

At Honolulu High School, before the name was changed to President William McKinley High School in 1907 after the story was published, the reporter stated:

Professor M.M. Scott, the principal of the high school, was kind enough to call all the pupils, who were not taking examinations, out on the front steps of the building, where the visitor could inspect them in the sunshine. The change in the color scheme from that of the schools below was astounding. Below were all the hues of the human spectrum, with brown and yellow predominating; here the tone was clearly white.