In 1839, King Kamehameha III proclaimed, by Declaration, the protection for both person and property in the kingdom by stating, “Protection is hereby secured to the persons of all the people; together with their lands, their building lots, and all their property, while they conform to the laws of the kingdom, and nothing whatever shall be taken from any individual except by express provision of the laws.” The Hawaiian Legislature, by resolution passed on October 26, 1846, acknowledged that the 1839 Declaration of Rights recognized “three classes of persons having vested rights in the lands,—1st, the government, 2nd, the landlord [Chiefs and Konohikis], and 3d, the tenant [natives] (Principles adopted by the Board of Commissioners to Quiet Land Titles, in their Adjudication of Claims Presented to Them, Resolution of the Legislative Council, Oct. 26, 1846).” Furthermore, the Legislature also recognized that the Declaration of 1839 “particularly recognizes [these] three classes of persons as having rights in the sale,” or revenue derived from the land as well.

In 1839, King Kamehameha III proclaimed, by Declaration, the protection for both person and property in the kingdom by stating, “Protection is hereby secured to the persons of all the people; together with their lands, their building lots, and all their property, while they conform to the laws of the kingdom, and nothing whatever shall be taken from any individual except by express provision of the laws.” The Hawaiian Legislature, by resolution passed on October 26, 1846, acknowledged that the 1839 Declaration of Rights recognized “three classes of persons having vested rights in the lands,—1st, the government, 2nd, the landlord [Chiefs and Konohikis], and 3d, the tenant [natives] (Principles adopted by the Board of Commissioners to Quiet Land Titles, in their Adjudication of Claims Presented to Them, Resolution of the Legislative Council, Oct. 26, 1846).” Furthermore, the Legislature also recognized that the Declaration of 1839 “particularly recognizes [these] three classes of persons as having rights in the sale,” or revenue derived from the land as well.

These three classes of vested rights, being mixed or undivided in the land, is also reflected in the kingdom’s first constitution in 1840, which states, “Kamehameha I was the founder of the kingdom, and to him belonged all the land from one end of the Islands to the other, though it was not his own private property. It belonged to the chiefs and people in common, of whom Kamehameha was the head, and had the management of the landed property.” The Chiefs and Konohikis carried out the management of the land under the direction of the King for the benefit of the Native Tenants. There is no other country in the world that can boast what a King did for his people in securing their rights in the lands of the kingdom.

By definition, a vested right is “a right belonging so absolutely, completely, and unconditionally to a person that it cannot be defeated by the act of any private person and that is entitled to governmental protection usually under a constitutional guarantee.” In 1846, the Hawaiian Legislature recognized that government lands acquired by conveyance remained “subject to the previous vested rights of tenants and others, which shall not have been divested by their own acts, or by operation of law (Statute Laws of Kamehameha III (1846), vol. 1, p. 99).” The Hawaiian Supreme Court in 1851 best articulated the mastery of these vested rights under Hawaiian law in Kekiekie v. Edward Dennis, 1 Haw. 42 (1851). Chief Justice William L. Lee stated, “the people’s lands were secured to them by the Constitution and laws of the Kingdom, and no power can convey them away, not even that of royalty itself.”

By definition, a vested right is “a right belonging so absolutely, completely, and unconditionally to a person that it cannot be defeated by the act of any private person and that is entitled to governmental protection usually under a constitutional guarantee.” In 1846, the Hawaiian Legislature recognized that government lands acquired by conveyance remained “subject to the previous vested rights of tenants and others, which shall not have been divested by their own acts, or by operation of law (Statute Laws of Kamehameha III (1846), vol. 1, p. 99).” The Hawaiian Supreme Court in 1851 best articulated the mastery of these vested rights under Hawaiian law in Kekiekie v. Edward Dennis, 1 Haw. 42 (1851). Chief Justice William L. Lee stated, “the people’s lands were secured to them by the Constitution and laws of the Kingdom, and no power can convey them away, not even that of royalty itself.”

On November 7, 1846, the Hawaiian Legislature enacted Joint resolutions on the subject of rights in lands and the leasing, purchasing and dividing of the same that sought to begin the process of dividing out the undivided rights of these three classes in the lands, but it was unsuccessful. The following year in December 1847, executive action was taken by the King in Privy Council to carry into effect a division of the vested rights that has come to be known as the Great Mahele [division]. A common misunderstanding is that the Great Mahele endeavored to divide all the rights of the three classes in the lands. The Great Mahele only divided the vested rights of the Chiefly class from the Government class in the lands. These divided rights over specific lands called ahupua‘a and ili‘aina remained subject to the rights of Native Tenants, who by application to the Minister of the Interior, who managed government lands, or to a particular Chief or Konohiki who managed lands that were separated from the government, could acquire a fee-simple title to their house lot and cultivating lands.

On December 18, 1847, the Privy Council unanimously passed a resolution accepting 7 rules prepared by Chief Justice William Lee that would guide the division of lands between the Government class, the Chiefly class and the Native Tenant class. According to Rule 2, “One third of the remaining lands of the Kingdom shall be set aside as the property of the Hawaiian Government, subject to the direction and control of His Majesty, as pointed out by the Constitution and laws. One third to the Chiefs and Konohikis in proportion to their possessions, to have and to hold to them, their heirs and Successors forever—and the remaining third to the Tenants, the actual possessors and cultivators of the soil, to have and to hold to them their heirs and successors forever (Privy Council Minutes, vol. 10, p. 129).” Rule 3 would apply to the Native Tenants and their division, which states, “The division between the Chiefs or the Konohikis and their Tenants, prescribed by rule second, shall take place, whenever any Chief, Konohiki or Tenant shall desire such a division, subject only to confirmation by the King in Privy Council.” The Rules of the Great Mahele is a living document and a condition of the management of the lands for the Government class and the Chief and Konohiki class. As a living document it remains a condition of land titles throughout the Hawaiian Islands.

After accepting the division of lands between Kamehameha III, in his private capacity as the highest of the Chiefly class, and the Government, the Legislature under An Act Relating to the Lands of His Majesty The King and the of the Government on June 7, 1848, recognized Kamehameha III’s private lands, which came to be known as Crown lands, as “subject only to the rights of tenants (Supplement to the Statute Laws of His Majesty, Kamehameha III (1848), p. 25),” and the Government lands “as subject always to the rights of tenants (p. 41).” The Board of Commissioners to Quiet Land Titles (Land Commission) was tasked with the additional duty to issue Land Commission Awards (LCAs) to Chiefs and Konohikis that received lands in the Great Mahele as well as to native tenants who submitted their claims with the Land Commission. The Land Commission, however, could only grant LCAs to those that filed their claims before February 14, 1848.

Chief Justice William Lee, who also served as President of the Land Commission, wrote an illuminating letter to Reverend Emerson from Wailua, O‘ahu, on the subject of native tenant rights and the lands of Chiefs and Konohikis. Emerson was concerned that not all of the native tenants have filed their claims with the Land Commission before the deadline of February 14, 1848, and was asking if they had therefore lost their rights in the land. Lee responded, “Should the tenants neglect to send in their claims, they will not lose their rights if their Konohiki present claims; for no title will be granted to the Konohiki without a clause reserving the rights of tenants (Letter to Reverend Emerson dated Jan. 12, 1848, Supreme Court Letter Book of Chief Justice Lee, June 3, 1847-April 18, 1854, Judiciary Dept., series 240, box 1, Hawai’i Archives).”

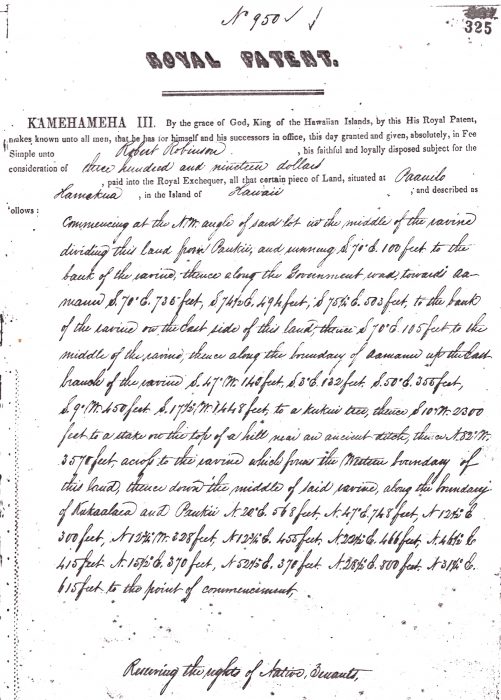

Lee was speaking to the vested rights of the Native Tenant class that was already secured under the constitution and laws of the Kingdom. In LCAs issued to the Chiefs and Konohikis who were assigned lands in the Great Mahele, there is the clause, “Aka, koe nae na kuleana on na Kanaka ma loko (Land Commission Award 8559-B, parcel 31, to W.C. Lunalilo for the iliaina of Kaluakou, Waikiki),” which is translated as “However, reserving the rights of Native Tenants within.” In Royal Patents that were in the English language, the clause “Reserving the rights of Native Tenants (Royal Patent Grant 950 to Robert Robinson)” was expressly written as a condition of the title.

Under Hawaiian law, all revenues derived from the lands of the Hawaiian Islands; whether by the Government through taxation, rent or sale, or from the Chiefs or Konohikis, through rent or sale, continue to have the vested rights of native tenants. This is what formed the basis as to why the Queen’s Hospital provided health care without charge to native Hawaiians in the nineteenth century because Queen’s Hospital acquired monies from the Government and from Queen Emma as a Chiefess who acquired lands from Mahele grantees, and after her death through the Queen Emma Trust. This is not to be confused with socialism, but rather management of the vested rights of Native Tenants that have and continue to remain in all the lands of the Hawaiian Islands.

As reported by the Pacific Commercial Advertiser in 1901, “The Queen’s Hospital was founded in 1859 by their Majesties Kamehameha IV and his consort Emma Kaleleonalani. The hospital is organized as a corporation and by the terms of its charter the board of trustees is composed of ten members elected by the society and ten members nominated by the Government… The charter also provides for the ‘establishment and putting into operation a permanent hospital at Honolulu, with a dispensary and all necessary furniture and appurtenances for the reception, accommodation and treatment of indigent sick and disabled Hawaiians, as well as such foreigners and others who may choose to avail themselves of the same.’ Under this construction all native Hawaiians have been cared for without charge, while for others a charge has been made of from $1 to $3 per day (Pacific Commercial Advertiser, July 31, 1901, p. 14).”

When the United States seized and occupied the Hawaiian Islands during the Spanish-American War, American laws were illegally imposed in the Hawaiian Kingdom that did not allow health care, at no cost, for Natives. The Hawaiian Kingdom Government annually appropriated $10,000.00 to Queen’s Hospital. Since the occupation began, the American authorities were considering the termination of this annual funding.

In 1901, Queen’s Hospital’s Chairman of the Board of Trustees, George W. Smith, explained, “There is a possibility that the legislative appropriation will be cut off after the first of the year, but even so we shall have funds enough to get along, although the hospital will be somewhat crippled. You see there is a provision in the United States Constitution that public property shall not be taken for private use, or that the people shall not be taxed to support private institutions. The Queen’s Hospital is, from the nature of its charter, a quasi-private institution. When it was chartered it was provided that all Hawaiians, of native birth, should be treated free of charge. Foreigners were to be treated by payment of fees (Pacific Commercial Advertiser, July 30, 1900, p. 2).”

In other words, American law would view Queen’s Hospital’s providing health care at no charge to Natives as race based. The following year, Smith argued, “Under our charter we are compelled to treat native Hawaiians free of charge and I do not see how it can be changed (Pacific Commercial Advertiser, July 31, 1901, p. 14).”

Although there is no express provision in the Charter or By-laws of Queen’s Hospital to provide health care at no cost to Natives, it was universally understood and recognized by the Kingdom’s Constitution and laws that Natives benefit from the revenues derived from the Government and the lands of Queen Emma because of their vested rights. Queen’s Hospital would eventually only receive landed revenues from the Queen Emma Trust, and in 1950, these lands were transferred from the trust to the Hospital. As the occupation progressed, Natives would eventually be denied healthcare at Queen’s Hospital without payment, and if they were unable to pay some could see relief if they were “indigent.”

All the actions taken with regard to Queen’s Hospital and the Queen Emma Trust can be summed up as not only a violation of the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom, but also a violation of international humanitarian law and human rights law. According to Vincent Bernard, Editorial: Occupation, 94 (885) International Review of the Red Cross 5 (Spring 2012):

“The notion that the occupier’s conduct towards the population of an occupied territory must be regulated underpins the current rules of humanitarian law governing occupation. Another pillar of this body of law is the duty to preserve the institutions of the occupied state. Occupation is not annexation; it is viewed as a temporary situation, and the Occupying Power does not acquire sovereignty over the territory concerned. Not only does the law endeavour to prevent the occupier from wrongfully exploiting the resources of the conquered territory; it also requires the occupier to provide for the basic needs of the population and to ‘restore, and ensure, as far as possible, public order and safety, while respecting, unless absolutely prevented, the laws in force in the country [Article 43, 1907 Hague Convention, IV]’. The measures taken by the occupier must therefore preserve the status quo ante (this is known as the conservationist principle).”

In December 2014,

In December 2014,  Before the re-filing, Dr. Sai met with Governor David Ige’s

Before the re-filing, Dr. Sai met with Governor David Ige’s