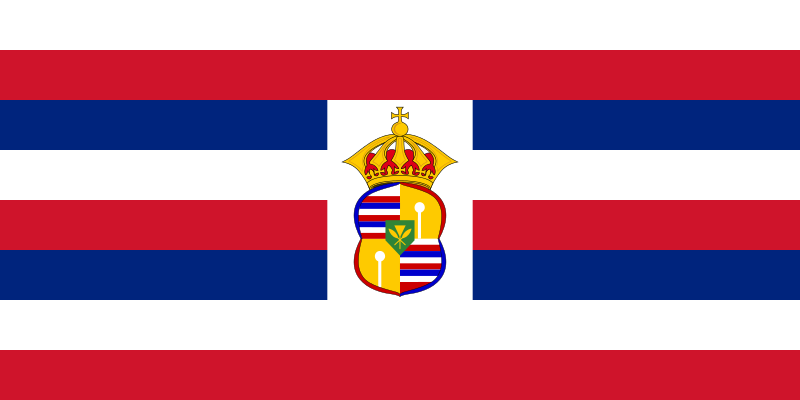

Another example of misinformation centers on the Hawaiian national flag. Lately, there is a common misunderstanding that the current flag that has the Union Jack at the top left corner is not Hawaiian, but rather British that was imposed here in the islands in 1843 by British Naval Officer Lord Paulet. According to the story published in the Honolulu Adverstiser in 2001, Gene Simeona of Honolulu, stated “he resurrected the ‘original’ Hawaiian green, red and yellow striped flag, destroyed by British navy Capt. Lord George Paulet when he seized Hawai‘i for five months in 1843.” Sonoda calls this flag the Kanaka Maoli flag.

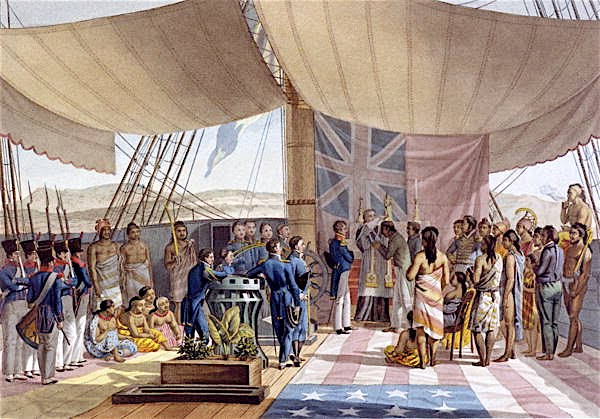

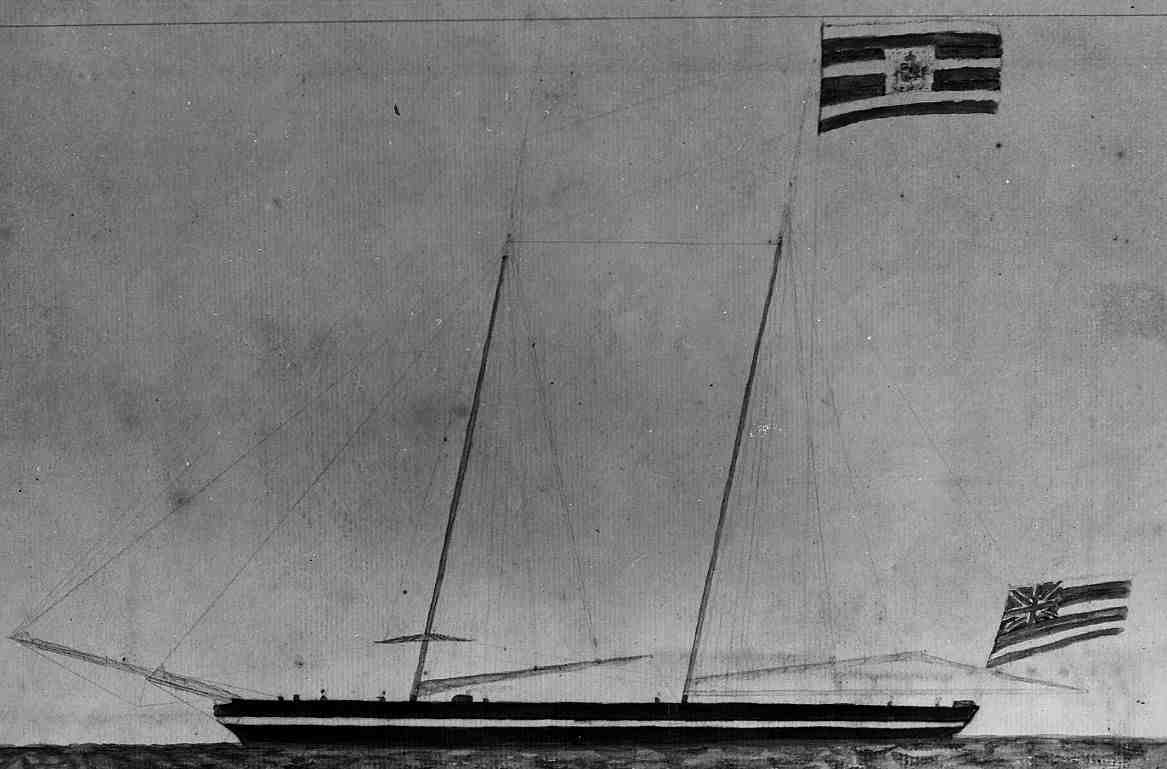

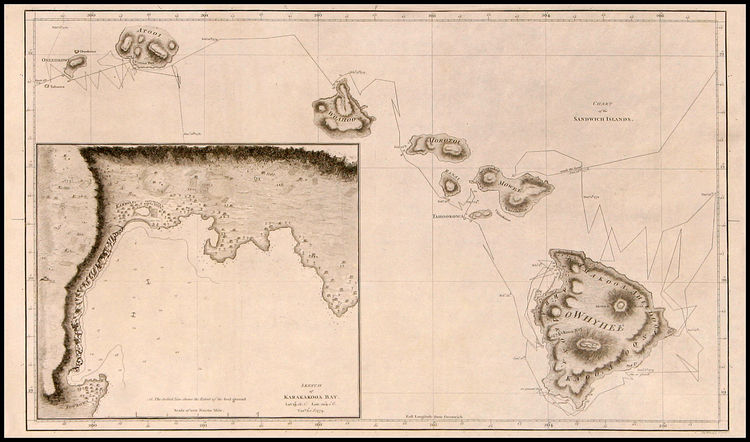

A very simple way to falsify or refute this claim is to show that the flag with the Union Jack existed before 1843. There is a lot of evidence that refutes this claim such as ship logs of foreign ships that visited the islands since 1816, which is the date the flag was created by order of Kamehameha I. Below are two portraits painted around 1819. The first portrait was painted in 1819 of the baptism of Kalanimoku, the Hawaiian Kingdom’s former Prime Minister on board the French ship Uranie after the death of Kamehameha I, and the second portrait was done sometime after 1819 of the Hawaiian ship commanded by Captain Alexander Adams during the reign of Kamehameha II. Both ships had the presence of Kamehameha II.

The second portrait is also called a flagship that has both the national flag and the royal flag. The royal flag, also called the royal ensign, is a flag that signals the presence of the Hawaiian monarch and in this portrait it signaled the presence of Kamehameha II on board. The royal ensign also flies at the residence of the Hawaiian monarch and wherever the monarch travels.

Sonoda’s claim that the Union Jack symbolizes British colonialism in Hawai‘i is also not accurate, because Kamehameha I joined the British Empire voluntarily, along with his principle chiefs, on February 25, 1794, when Kamehameha entered into an agreement with British Captain George Vancouver. The agreement provided that the British government would not interfere with the kingdom’s religion, government and economy—“the chiefs and priests, were to continue as usual to officiate with the same authority as before in their respective stations.”

If the island Kingdom of Hawai‘i was colonized, Kamehameha would not have maintained the status of King, but would have been replaced by a British Governor-General. Queen Victoria recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign State on November 28, 1843 after Lord Paulet’s seizure from February to July 1843. Therefore, Sonodo’s other claim of Lord Paulet’s seizure is true, but there is no evidence that the green, red and yellow striped flag ever existed.