Queen Lili‘uokalani arrived in Washington, D.C., on the evening of January 24, 1897, and departed on July 10, 1898. Her purpose was to use her stately influence to correct the wrong that occurred when her government of the Hawaiian Kingdom was unlawfully overthrown with the participation of U.S. troops on January 17, 1893. The Queen’s conditional surrender stated:

I, Liliuokalani, by the grace of God and under the constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a provisional government of and for this Kingdom.

That I yield to the superior force of the United States of America, whose minister plenipotentiary, His Excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United States troops to be landed at Honolulu and declared that he would support the said provisional government.

Now, to avoid any collision of armed forces and perhaps the loss of life, I do, under this protest, and impelled by said force, yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon the facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.

U.S. President Grover Cleveland initiated a presidential investigation on March 11, 1893, by appointing Special Commissioner James Blount to travel to the Hawaiian Islands and provide periodic reports to the U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham. Commissioner Blount arrived in the Islands on March 29th after which he “directed the removal of the flag of the United States from the government building and the return of the American troops to their vessels.” His last and final report was dated 17 July 1893, and on 18 October 1893, Secretary of State Gresham reported to the President:

The Provisional Government was established by the action of the American minister and the presence of the troops landed from the Boston, and its continued existence is due to the belief of the Hawaiians that if they made an effort to overthrow it, they would encounter the armed forces of the United States.

The earnest appeals to the American minister for military protection by the officers of that Government, after it had been recognized, show the utter absurdity of the claim that it was established by a successful revolution of the people of the Islands. Those appeals were a confession by the men who made them of their weakness and timidity. Courageous men, conscious of their strength and the justice of their cause, do not thus act. …

The Government of Hawaii surrendered its authority under a threat of war, until such time only as the Government of the United States, upon the facts being presented to it, should reinstate the constitutional sovereign…

Should not the great wrong done to a feeble but independent State by an abuse of the authority of the United States be undone by restoring the legitimate government? Anything short of that will not, I respectfully submit, satisfy the demands of justice.

On December 18, 1893, President Cleveland delivered a message to the Congress on his investigation into the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom Government. The President concluded that the “military occupation of Honolulu by the United States…was wholly without justification, either as an occupation by consent or as an occupation necessitated by dangers threatening American life and property.” He also determined “that the provisional government owes its existence to an armed invasion by the United States.” Finally, the President admitted that by “an act of war…the Government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown.”

Through executive mediation between the Queen and the new U.S. Minister to the Hawaiian Islands, Albert Willis, that lasted from November 13th through December 18th, an agreement of peace was reached. According to the executive agreement, by exchange of notes, the President committed to restoring the Queen as the constitutional sovereign, and the Queen agreed, after being restored, to grant a full pardon to the insurgents. Political wrangling in the Congress, however, blocked President Cleveland from carrying out his obligation of restoration of the Queen.

While she was in Washington, D.C., the Queen received word that the insurgents, calling themselves the Republic of Hawai‘i since July 4, 1894, signed a treaty of cession with President William McKinley on June 16, 1897. The following day, Queen Lili‘uokalani filed the following protest with U.S. State Department:

I, Lili‘uokalani of Hawai‘i, by the will of God named heir apparent on the tenth day of April, A.D. 1877, and by the grace of God Queen of the Hawaiian Islands on the seventeenth day of January, A.D. 1893, do hereby protest against the ratification of a certain treaty, which, so I am informed, has been signed at Washington by Messrs. Hatch, Thurston, and Kinney, purporting to cede those Islands to the territory and dominion of the United States. I declare such a treaty to be an act of wrong toward the native and part-native people of Hawaii, an invasion of the rights of the ruling chiefs, in violation of international rights both toward my people and toward friendly nations with whom they have made treaties, the perpetuation of the fraud whereby the constitutional government was overthrown, and, finally, an act of gross injustice to me.

Because the official protests made by me on the seventeenth day of January, 1893, to the so-called Provisional Government was signed by me, and received by said government with the assurance that the case was referred to the United States of America for arbitration.

Because that protest and my communications to the United States Government immediately thereafter expressly declare that I yielded my authority to the forces of the United States in order to avoid bloodshed, and because I recognized the futility of a conflict with so formidable a power.

Because the President of the United States, the Secretary of State, and an envoy commissioned by them reported in official documents that my government was unlawfully coerced by the forces, diplomatic and naval, of the United States; that I was at the date of their investigations the constitutional ruler of my people.

Because neither the above-named commission nor the government which sends it has ever received any such authority from the registered voters of Hawaii, but derives its assumed powers from the so-called committee of public safety, organized on or about the seventeenth day of January, 1893, said committee being composed largely of persons claiming American citizenship, and not one single Hawaiian was a member thereof, or in any way participated in the demonstration leading to its existence.

Because my people, about forty thousand in number, have in no way been consulted by those, three thousand in number, who claim the right to destroy the independence of Hawaii. My people constitute four-fifths of the legally qualified voters of Hawaii, and excluding those imported for the demands of labor, about the same proportion of the inhabitants.

Because said treaty ignores, not only the civic rights of my people, but, further, the hereditary property of their chiefs. Of the 4,000,000 acres composing the territory said treaty offers to annex, 1,000,000 or 915,000 acres has in no way been heretofore recognized as other than the private property of the constitutional monarch, subject to a control in no way differing from other items of a private estate.

Because it is proposed by said treaty to confiscate said property, technically called the crown lands, those legally entitled thereto, either now or in succession, receiving no consideration whatever for estates, their title to which has been always undisputed, and which is legitimately in my name at this date.

Because said treaty ignores, not only all professions of perpetual amity and good faith made by the United States in former treaties with the sovereigns representing the Hawaiian people, but all treaties made by those sovereigns with other and friendly powers, and it is thereby in violation of international law.

Because, by treating with the parties claiming at this time the right to cede said territory of Hawaii, the Government of the United States receives such territory from the hands of those whom its own magistrates (legally elected by the people of the United States, and in office in 1893) pronounced fraudulently in power and unconstitutionally ruling Hawaii.

Therefore I, Lili‘uokalani of Hawaii, do hereby call upon the President of that nation, to whom alone I yielded my property and my authority, to withdraw said treaty (ceding said Islands) from further consideration. I ask the honorable Senate of the United States to decline to ratify said treaty, and I implore the people of this great and good nation, from whom my ancestors learned the Christian religion, to sustain their representatives in such acts of justice and equity as may be in accord with the principles of their fathers, and to the Almighty Ruler of the universe, to him who judgeth righteously, I commit my cause.

Done at Washington, District of Columbia, United States of America, this seventeenth day of June, in the year eighteen hundred and ninety-seven.

[signed] Lili‘uokalani

[signed] Joseph Heleluhe )

[signed] Wakeki Heleluhe ) Witness to signature

[signed] Julius A. Palmer )

From Washington, the Queen notified two political organizations in Hawai‘i, the Hui Aloha ‘Āina (Hawaiian Patriotic League) and the Hui Kālaiʻāina (Hawaiian Political Association) to gather signature petitions against the treaty by the people. Through the direction of the Queen, representatives of these organizations that arrived in Washington on December 6, 1897, managed to get enough Senators to not ratify the treaty. By March of 1898, the treaty failed.

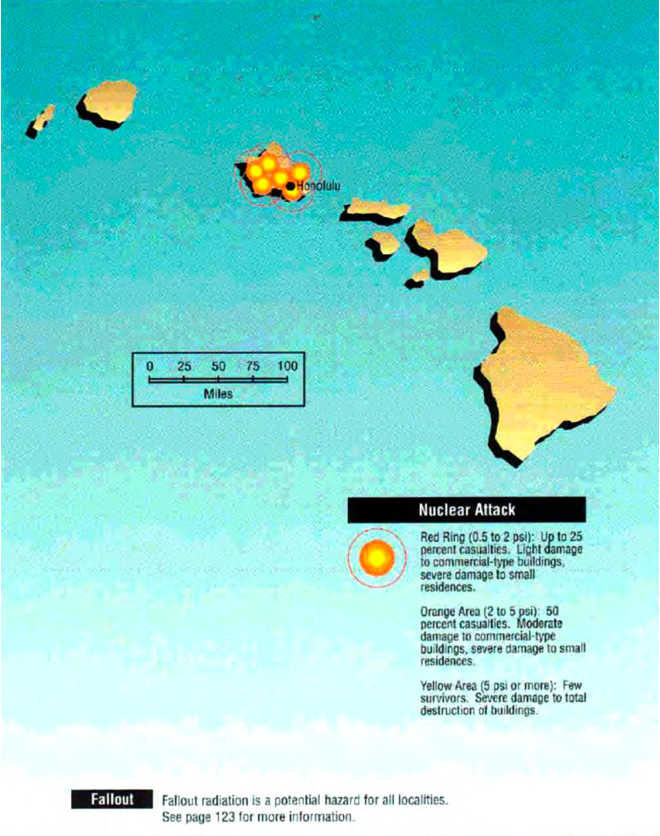

When the Congress declared war upon Spain the following month on April 25, 1898, the Congress set a course to unilaterally seize the Hawaiian Islands at the height of the Spanish-American War. The war did not end until December 10, 1898. On July 6, 1898, the Congress passed a joint resolution of annexation, and President McKinley signed it into American law the following day.

The congressional records, however, reveal that Congressmen and Senators were fully aware that a joint resolution is not a treaty, and that any American legislation, whether by an Act or a Joint Resolution, is limited in authority to American territory and not foreign territory. One of these Senators was Senator William Allen of Nebraska that stated on the floor of the Senate on July 4, 1898, when the joint resolution of annexing the Hawaiian Islands was being debated. Senator Allen stated:

The Constitution and the statutes are territorial in their operation; that is, they can not have any binding force or operation beyond the territorial limits of the government in which they are promulgated. In other words, the Constitution and statutes can not reach across the territorial boundaries of the United States into the territorial domain of another government and affect that government or persons or property therein.

Two years later, on February 28, 1900, during a debate on senate bill no. 222 that proposed the establishment of the Territory of Hawai‘i, Senator Allen reiterated, “I utterly repudiate the power of Congress to annex the Hawaiian Islands by a joint resolution such as passed the Senate. It is ipso facto null and void.”

In its 1824 decision in The Apollon, the U.S. Supreme Court stated that the “laws of no nation can justly extend beyond its own territories except so far as regards its own citizens. They can have no force to control the sovereignty or rights of any other nation within its own jurisdiction.” The Hawaiian Supreme Court also cited The Apollon in its 1858 decision, In re Francis de Flanchet, where the court stated that the “laws of a nation cannot have force to control the sovereignty or rights of any other nation within its own jurisdiction. And however general and comprehensive the phrases used in the municipal laws may be, they must always be restricted in construction, to places and persons upon whom the Legislature have authority and jurisdiction.” Both the Apollon and Flanchet cases addressed the imposition of French municipal laws within the territories of the United States and the Hawaiian Kingdom. The Hawaiian Kingdom and the United States were fully aware of the limitation of a country’s legislation so it stands to reason that the Queen knew this as well.

In a 1988 legal opinion by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel, the Acting Assistant Attorney General, Douglas Kmiec, agreed. After covering the limitation of congressional authority, which, in effect, confirmed the statements made by Senator Allen, Acting Assistant Attorney General Kmiec concluded that it is “unclear which constitutional power Congress exercised when it acquired Hawaii by joint resolution.” If it was unclear how Congress “acquired Hawaii by joint resolution,” it would be equally unclear how Congress could establish the Territory of Hawai‘i in 1900, and the State of Hawai‘i in 1959.

From 1893 to the writing of her book, Hawai‘i’s Story by Hawai‘i’s Queen, that was published in 1898 after she returned from Washington, Queen Lili‘uokalani relied on justice and the law to preserve the rights of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its people in the face of American racism and its pursuit of becoming a naval power in the world. After exhausting all diplomatic and legal efforts, she could not stop the American theft of a country not theirs. So, she ends her final chapter with the story about Naboth’s vineyard and a stark warning to the American people.

Oh, honest Americans, as Christians, hear me for my down-trodden people! Their form of government is as dear to them as yours is precious to you. Quite as warmly as you love your country, so they love theirs. With all your goodly possessions, covering a territory so immense that there yet remain parts unexplored, possessing islands that, although near at hand, had to be neutral ground in time of war, do not covet the vineyard of Naboth’s so far from your shores, lest the punishment of Ahab fall upon you, if not in your day in that of your children, for ‘be not deceived, God is not mocked.’ The people to whom your fathers told of the living God, and taught to call ‘Father,’ and whom the sons now seek to despoil and destroy, are crying aloud to Him in their time of trouble; and He will keep His promise, and will listen to the voices of His Hawaiian children lamenting for their homes.

It is for them that I would give the last drop of my blood; it is for them that I would spend, nay, am spending, everything belonging to me. Will it be in vain? It is for the American people and their representatives in Congress to answer these questions. As they deal with me and my people, kindly, generously, and justly, so may the Great Ruler of all nations deal with the grand and glorious nation of the United States of America.

The story of Naboth comes from the Old Testament of the Bible. According to 1 Kings 21:1-28:

Some time later there was an incident involving a vineyard belonging to Naboth the Jezreelite. The vineyard was in Jezreel, close to the palace of Ahab king of Samaria.

2 Ahab said to Naboth, “Let me have your vineyard to use for a vegetable garden, since it is close to my palace. In exchange I will give you a better vineyard or, if you prefer, I will pay you whatever it is worth.”

3 But Naboth replied, “The Lord forbid that I should give you the inheritance of my ancestors.”

4 So Ahab went home, sullen and angry because Naboth the Jezreelite had said, “I will not give you the inheritance of my ancestors.” He lay on his bed sulking and refused to eat.

5 His wife Jezebel came in and asked him, “Why are you so sullen? Why won’t you eat?”

6 He answered her, “Because I said to Naboth the Jezreelite, ‘Sell me your vineyard; or if you prefer, I will give you another vineyard in its place.’ But he said, ‘I will not give you my vineyard.’”

7 Jezebel his wife said, “Is this how you act as king over Israel? Get up and eat! Cheer up. I’ll get you the vineyard of Naboth the Jezreelite.”

8 So she wrote letters in Ahab’s name, placed his seal on them, and sent them to the elders and nobles who lived in Naboth’s city with him.

9 In those letters she wrote: “Proclaim a day of fasting and seat Naboth in a prominent place among the people.

10 But seat two scoundrels opposite him and have them bring charges that he has cursed both God and the king. Then take him out and stone him to death.”

11 So the elders and nobles who lived in Naboth’s city did as Jezebel directed in the letters she had written to them.

12 They proclaimed a fast and seated Naboth in a prominent place among the people.

13 Then two scoundrels came and sat opposite him and brought charges against Naboth before the people, saying, “Naboth has cursed both God and the king.” So they took him outside the city and stoned him to death.

14 Then they sent word to Jezebel: “Naboth has been stoned to death.”

15 As soon as Jezebel heard that Naboth had been stoned to death, she said to Ahab, “Get up and take possession of the vineyard of Naboth the Jezreelite that he refused to sell you. He is no longer alive, but dead.”

16 When Ahab heard that Naboth was dead, he got up and went down to take possession of Naboth’s vineyard.

17 Then the word of the Lord came to Elijah the Tishbite:

18 “Go down to meet Ahab king of Israel, who rules in Samaria. He is now in Naboth’s vineyard, where he has gone to take possession of it.

19 Say to him, ‘This is what the Lord says: Have you not murdered a man and seized his property?’ Then say to him, ‘This is what the Lord says: In the place where dogs licked up Naboth’s blood, dogs will lick up your blood—yes, yours!’”

20 Ahab said to Elijah, “So you have found me, my enemy!” “I have found you,” he answered, “because you have sold yourself to do evil in the eyes of the Lord.

21 He says, ‘I am going to bring disaster on you. I will wipe out your descendants and cut off from Ahab every last male in Israel—slave or free.

22 I will make your house like that of Jeroboam son of Nebat and that of Baasha son of Ahijah, because you have aroused my anger and have caused Israel to sin.’

23 “And also concerning Jezebel the Lord says: ‘Dogs will devour Jezebel by the wall of Jezreel.’

24 “Dogs will eat those belonging to Ahab who die in the city, and the birds will feed on those who die in the country.”

25 (There was never anyone like Ahab, who sold himself to do evil in the eyes of the Lord, urged on by Jezebel his wife.

26 He behaved in the vilest manner by going after idols, like the Amorites the Lord drove out before Israel.)

27 When Ahab heard these words, he tore his clothes, put on sackcloth and fasted. He lay in sackcloth and went around meekly.

28 Then the word of the Lord came to Elijah the Tishbite:

29 “Have you noticed how Ahab has humbled himself before me? Because he has humbled himself, I will not bring this disaster in his day, but I will bring it on his house in the days of his son.”

Since 1893, the United States has not treated the Hawaiian people fairly or justly. Their lands have been taken, their rights to free healthcare at Queen’s Hospital has been denied, and they continue to suffer from the high cost of living, which has driven the majority of the Hawaiian people to live in the United States. Native Hawaiians are the majority in the prisons. All of this did not exist before the American occupation began in 1893.

As customary international law concludes that despite the unlawful overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 and the unilateral seizure of the Hawaiian Islands in 1898, the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as a State under a prolonged occupation. Customary international law also reveals that war crimes have and continue to be committed by officials of the United States and the State of Hawai‘i, which will lead to their prosecutions. And the current state of politics in the United States is so revulsive and hateful, it appears to be literally tearing the United States in half.

Is this the “punishment of Ahab” that the Queen warned of?