On January 15, 2026, the British Museum in London opened an exhibition on the Hawaiian Kingdom. The exhibition will last until May 25, 2026.

Category Archives: International Relations

KHON Television Show “Aloha Authentic” with Kamaka Pili Interviews Dr. Keanu Sai on the Hawaiian Kingdom

Hawaiian Kingdom has Treaties with 154 Member States of the United Nations

As an independent State in the nineteenth century, the Hawaiian Kingdom maintained treaties with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Netherlands, the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States.

Despite the unlawful overthrow of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by United States forces on January 17, 1893, international law provides for the continued existence of the Hawaiian State even when the United States unilaterally annexed the Hawaiian Islands on July 7, 1898, by a congressional law during the Spanish-American War. For information of the American occupation, see chapter 21 “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire” in Oxford University Press’ publication of Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age. Because the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist so do its treaties.

After the American overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government, States were led to believe that the Hawaiian Kingdom had ceased to exist and became a part of the United States in 1898. Shattering this narrative was the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as a State and the Council of Regency as its restored government, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, in 1999.

The 20th century ushered in new States as successors to their predecessor States where the number of States in 1893 that numbered 44 would exponentially rise to 193 States that are members of the United Nations (“UN”). These successor States arose because of the First and Second World Wars and through decolonization of former colonial and trust territories.

When a successor State is established, the question arises regarding treaties of the predecessor State with a third State and whether it is binding or not on the successor State. For example, in June of 1961, New Zealand and Great Britain entered into a treaty that concerned air services between the former and the British territories of Western Samoa and Fiji. When Western Samoa became a successor State to Great Britain on January 1, 1962, the 1961 treaty remained binding on Western Samoa after its independence from Great Britain. In 1997, Western Samoa officially changed its name to Samoa.

According to the 1978 Vienna Convention on Succession of States in respect of Treaties, Article 24 states:

1. A bilateral treaty which at the date of the succession of States was in force in respect of the territory to which the succession of States relates is considered as being in force between a newly independent State and the other State party when: (a) they expressly so agree; or (b) by reason of their conduct they are to be considered as having agreed.

2. A treaty considered as being in force under paragraph 1 applies in the relations between the newly independent State and the other State party from the date of the succession of States, unless a different intention appears from their agreement or is otherwise established.

The successor States of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s treaty partners, were not aware, at the time of their independence, that the Hawaiian Kingdom continued to exist as a State, therefore, neither the newly independent States nor the Hawaiian Kingdom could declare “within a reasonable time after the attaining of independence, that the treaty is regarded as no longer in force between them.” Until there is clarification of the successor States’ intentions, as to a common understanding with the Hawaiian Kingdom regarding the continuance in force of the Hawaiian treaty with their predecessor State, the Hawaiian Kingdom will presume the continuance in force of its treaties with the successor States. The majority of Member States of the United Nations are successor States to treaties with the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The Hawaiian Kingdom has treaties with 154 Member States of the United Nations. 14 treaties with original States and 140 treaties with their successor States.

HAWAIIAN-AMERICAN TREATY: Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Palau, and the Philippines.

HAWAIIAN-AUSTRO-HUNGARIAN TREATY: Austria and Hungary

HAWAIIAN-BELGIAN TREATY: Burundi, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Rwanda.

HAWAIIAN-BRITISH TREATY: Afghanistan, Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, The Bahamas, Bahrain, Bangladesh, Barbados, Belize, Bhutan, Botswana, Brunei Darussalam, Cameroon, Canada, Cyprus, Egypt, Eswatini, Fiji, Gambia, Ghana, Grenada, Guyana, India, Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Jamaica, Jordan, Kenya, Kiribati, Kuwait, Lesotho, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Malta, Mauritius, Myanmar, Namibia, Nauru, Nepal, New Zealand, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Qatar, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tonga, Trinidad and Tobago, Tuvalu, Uganda, United Arab Emirates, United Republic of Tanzania, Vanuatu, Yemen, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

HAWAIIAN-DUTCH TREATY: Indonesia and Suriname.

HAWAIIAN-FRENCH TREATY: Algeria, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Gabon, Guinea, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Lebanon, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Senegal, Syrian Arab Republic, Togo, Tunisia, Vanuatu, and Viet Nam.

HAWAIIAN-ITALIAN TREATY: Libya and Somalia.

HAWAIIAN-JAPANESE TREATY: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and the Republic of Korea.

HAWAIIAN-PORTUGUESE TREATY: Angola, Cabo Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Sao Tome and Principe, and Timor-Leste.

HAWAIIAN-RUSSIAN TREATY: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Mongolia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Republic of Moldova, Slovenia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

HAWAIIAN-SPANISH TREATY: Cuba and Equatorial Guinea.

HAWAIIAN-SWEDISH-NORWEGIAN TREATY: Sweden and Norway.

VIDEOS of the Kamehameha Schools Presentation “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire: A Conversation with Dr. David Keanu Sai”

Below is the video of Dr. Keanu Sai’s presentation on his recent chapter “Hawai‘iʻs Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire” published by Englandʻs Oxford University Pressʻ Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age in December of 2024.

Below is the video of questions and answers of Dr. Keanu Sai following his presentation.

VIDEO of the Book Launch at the University of Hawai‘i of Oxford University Press’ publication of “Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age” with a Chapter on the American Occupation of Hawai‘i

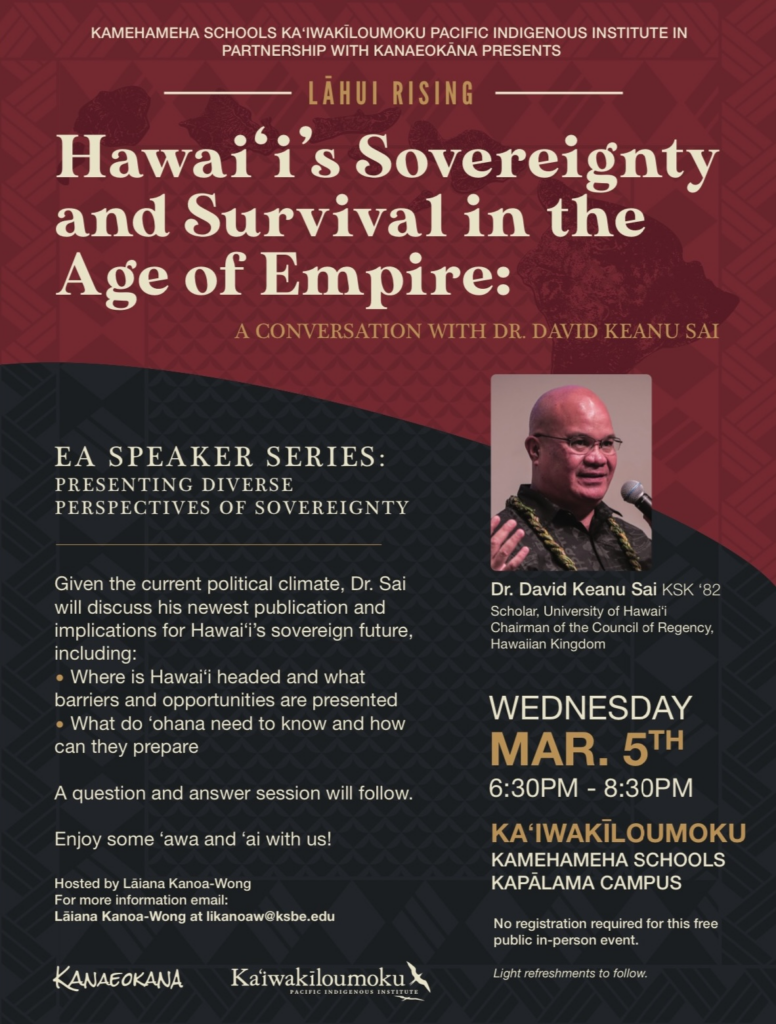

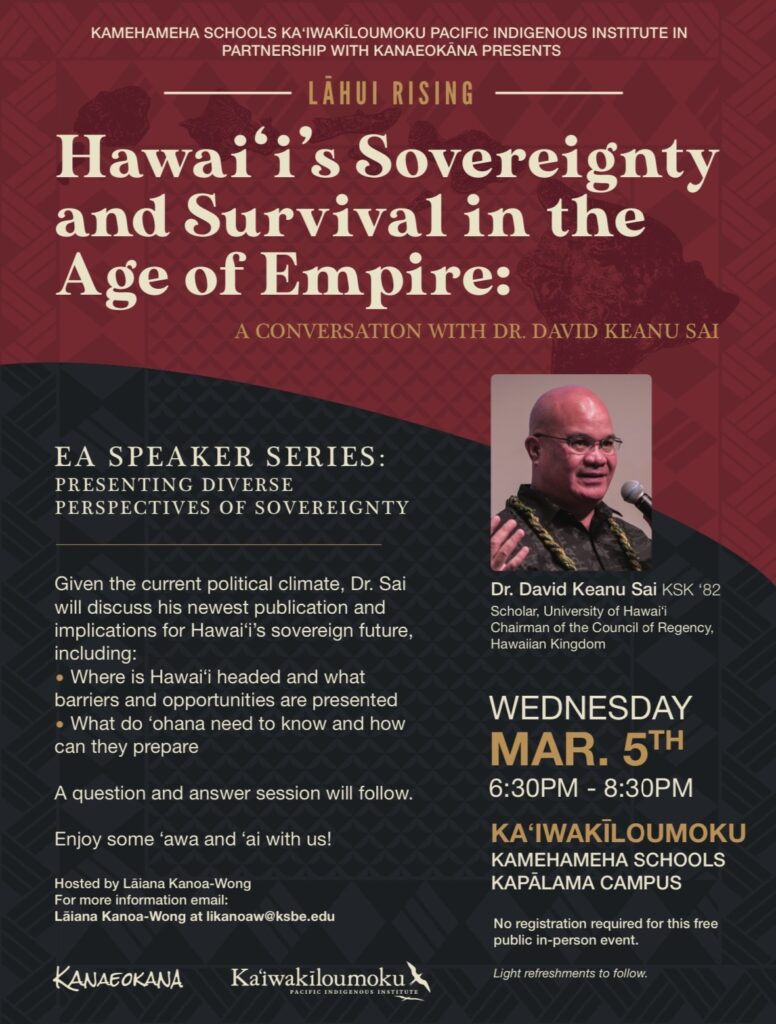

Kamehameha Schools Presents “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire: A Conversation with Dr. David Keanu Sai”

Dr. Keanu Sai, a graduate of the Kamehameha Schools Kapālama campus in 1982 has been invited by Kamehameha Schools Ka‘iwakīloumoku Pacific Indigenous Institute, in partnership with Kanaeokāna, for a presentation on March 5, 2025, with questions and answers to follow about his recent chapter “Hawai‘iʻs Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire” published by Englandʻs Oxford University Pressʻ Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age in December of 2024. No registration is required for this free public in-person event and light refreshments to follow.

The public is encouraged to attend because Dr. Saiʻs presentation will get into the operational plan for transitioning the State of Hawai‘i into a military government of Hawai‘i and the impact it will have on the population of Hawai‘i, e.g. health care, land, taxes, cost of living. The session will be recorded and uploaded on Kanaeokana’s website.

The session will be recorded and uploaded on Kanaeokana’s YouTube channel.

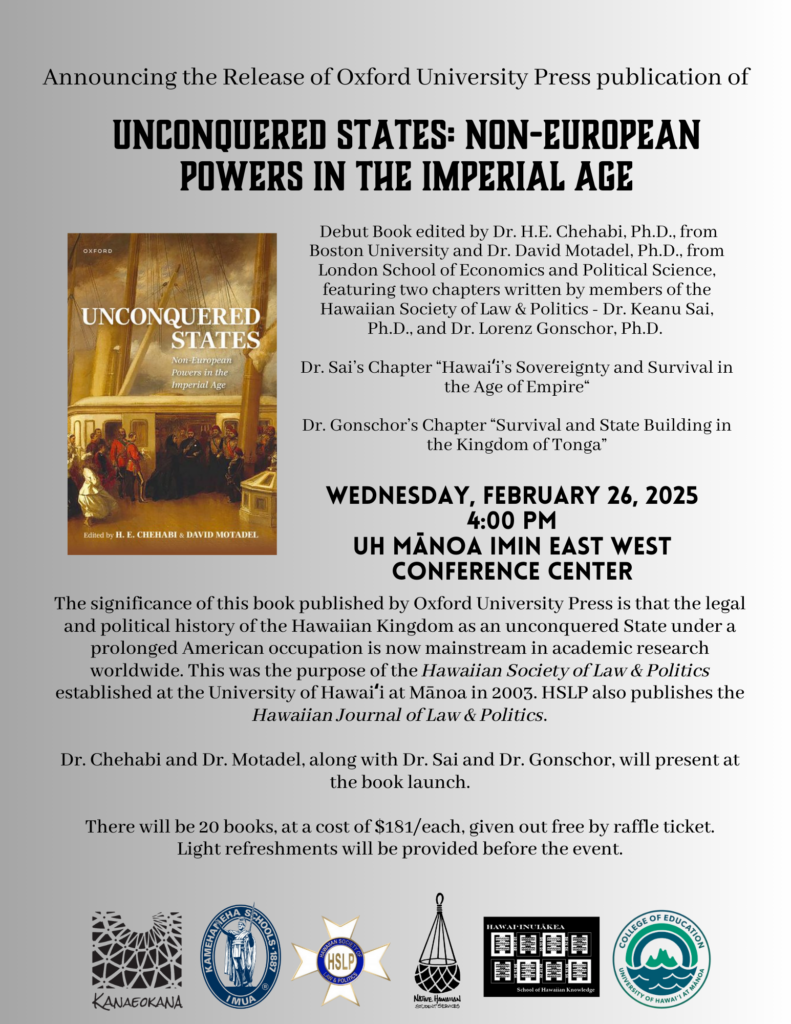

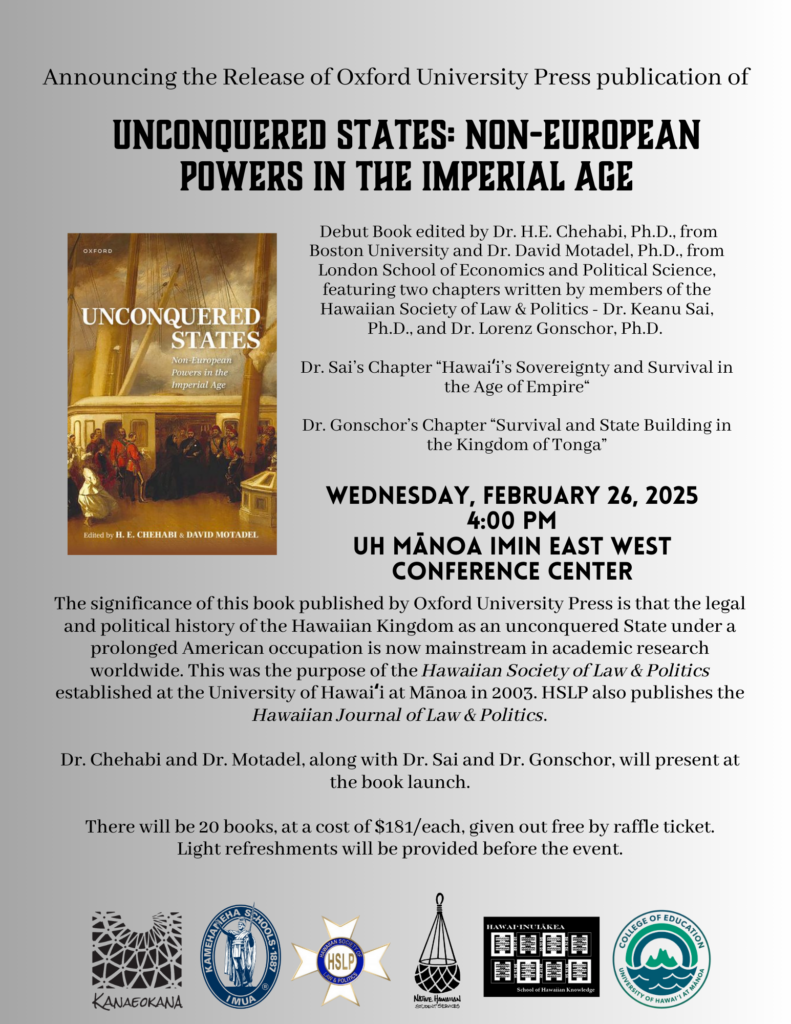

Book Launch Tomorrow at the University of Hawai‘i of Oxford University Press’ publication of “Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age” with a Chapter on the American Occupation of Hawai‘i

Tomorrow will be the official book launch of Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age published by England’s Oxford University Press in December of 2024. Dr. Keanu Sai is a contributor of a chapter in the book titled “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire.” In his chapter Dr. Sai

In his chapter, Dr. Sai covers: the legal and political history of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the evolution of governance as a constitutional monarchy, the unlawful overthrow of the government by United States troops in 1893, the prolonged American occupation since 1893, the restoration of the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1997 by a Council of Regency, and the recognition of the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom, as a State, and the Council of Regency, as its provisional government, by the Permanent Court of Arbitration, The Hague, Netherlands, in the 1999-2001 international arbitration case Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom. He concludes his chapter with:

Despite over a century of revisionist history, “the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign State is grounded in the very same principles that the United States and every other State have relied on for their own legal existence.” The Hawaiian Kingdom is a magnificent story of perseverance and continuity.

THE EVENT WILL BE LIVE STREAMED ON FACEBOOK STARTING AT 3:30pm HI TIME

KITV Island Life Live—Dr. Keanu Sai talks about his recent publication by Oxford University Press on the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom

On KITV Island Life Live yesterday, Dr. Keanu Sai talks about his recent chapter titled “Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire” in a book Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age. The book was published by Oxford University Press in December of 2024. Be sure to download Dr. Sai’s chapter by clicking the link above.

Pascal’s Substack—The Kingdom of Hawaii: Year 132 under U.S. Occupation

On January 4, 2025, Pascal Lottaz, a Professor for Neutrality Studies at the Waseda Institute for Advanced Study, (Waseda University), in Tokyo, posted a review of Dr. Keanu Sai’s chapter on Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire in Professor H.E. Chehabi and Professor David Motadel’s book Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age published by Oxford University Press.

Neutrality Studies Podcast: EX-Army Officer WAGES LAWFARE To End Illegal Occupation of Hawaii | Dr. Keanu Sai

Dr. Keanu Sai was invited to do a podcast interview by Professor Pascal Lottaz on the subject of the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, a Neutral State. Professor Lottaz is an Assistant Professor for Neutrality Studies at the Waseda Institute for Advanced Study in Tokyo. He is a also a researcher at Neutrality Studies, where its YouTube channel, which airs their podcasts, has 153,000 subscribers worldwide.

Oxford University Press will make it Official—Hawai‘i is the Longest Occupation in Modern History

With Oxford University Press (OUP) upcoming release, on December 30, 2024, of Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age with a chapter by Dr. Keanu Sai on the Hawaiian Kingdom and its continued existence as a State despite having been under a prolonged American occupation since 1893, it will make it official that Hawai‘i is the longest occupation in modern history. Previously, it was thought that the longest occupation was Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and East Jerusalem that began in 1967.

The reach of OUP is worldwide. In all its publications it states “Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford, Auckland, Cape Town, Dar es Salaam, Hong Kong, Karachi, Kuala Lumpur, Madrid, Melbourne, Mexico City, Nairobi, New Delhi, Shanghai, Taipei, and Toronto. With offices in Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Chile, Czech Republic, France, Greece, Guatemala, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Poland, Portugal, Singapore, South Korea, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, and Vietnam.”

Dr. Sai’s chapter has effectively pierced the false narrative that has plagued Hawai‘i’s population and the world that Hawai‘i is an American state, rather than an occupied State. The Hawaiian Kingdom’s continued existence as an occupied State is not a legal argument but rather a legal fact with consequences under international law. Dr. Sai concludes his chapter with:

Despite over a century of revisionist history, “the continuity of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a sovereign State is grounded in the very same principles that the United States and every other State have relied on for their own legal existence.” The Hawaiian Kingdom is a magnificent story of perseverance and continuity.

With the world knowing about the American occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom it will assist in facilitating compliance by the Hawai‘i Army National Guard with the law of occupation so that the American occupation will eventually come to an end by a treaty of peace.

Oxford University Press to release “Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age” with a chapter on the Hawaiian Kingdom

On December 30, 2024, Oxford University Press will be releasing a book titled Unconquered States: Non-European Powers in the Imperial Age. The editors of the book, Professor H. E. Chehabi from Boston University and Professor David Motadel from the London School of Economics and Political Science, invited 23 scholars from around the world to contribute their scholarship. Dr. Keanu Sai is the author of chapter 21—Hawai‘i’s Sovereignty and Survival in the Age of Empire.

Here are the reviews:

“This is an ingenious collection, a book on international history in the 19th and 20th centuries that really does, for once, “fill a gap.” By countering our simple assumption that the West’s imperial and colonial drives swallowed up all of Africa and Asia in the post-1850 period, Chehabi and Motadel’s fine collection of case-studies of nations that managed to stay free—from Abyssinia to Siam, Japan to Persia—gives us a more rounded and complex view of the international Great-Power scene in those decades. This is really fine revisionist history.”—Paul Kennedy, Yale University

“This is an excellent collection of scholars writing on an important set of states, which deserve to be considered together.”—Kenneth Pomeranz, University of Chicago

“Carefully curated and with an excellent introduction that provides an analytical frame, this book offers a global history of “unconquered” countries in the imperial age that is original in its perspective and composition.”—Sebastian Conrad, Free University of Berlin

“The book offers an insightful comparative analysis of political forms and relationships in non-European countries from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. The “non-conquered states” of Asia and Africa are show as sometimes resisting and but often accommodating in innovative ways European political forms and military and diplomatic techniques. The particular appeal of the essays lies in their effort to bring to the surface and critically assess the indigenous histories and struggles that enabled these political formations, each in their own way, to respond to the challenges of modernization. This is global history at its kaleidoscopic best.”—Martti Koskenniemi, University of Helsinki

Oxford University Press is the gold standard for academic publishing in the world and to have the untold story of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its continued existence under an American occupation is a monumental feat for the Council of Regency’s strategic plan under Phase II—exposure of Hawaiian Statehood. Dr. Sai is not only a Hawaiian scholar and political scientist, but he is also Chairman of the acting Council of Regency.

When the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom was restored in 1997, as an acting Council of Regency under Hawaiian constitutional law and the legal doctrine of necessity, it approached the prolonged American occupation with a strategic plan that entailed three phases:

Phase I: Verification of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an Independent State and subject of international law where a reputable international body must verify the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State.

Phase II: Exposure of Hawaiian Statehood within the framework of international law and the law of occupation as it affects the realm of politics and economics at both the international and domestic levels. Phase II will focus on individual accountability and compliance to the law of occupation.

Phase III: Restoration of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State and a subject of international law, which is when the occupation will come to an end by a treaty of peace.

On November 8, 1999, international arbitration proceedings were initiated at the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in The Hague, Netherlands, in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom, PCA Case no. 1999-01. At its website, the PCA described the dispute as:

Lance Paul Larsen, a resident of Hawaii, brought a claim against the Hawaiian Kingdom by its Council of Regency (“Hawaiian Kingdom”) on the grounds that the Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom is in continual violation of: (a) its 1849 Treaty of Friendship, Commerce and Navigation with the United States of America, as well as the principles of international law laid down in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969 and (b) the principles of international comity, for allowing the unlawful imposition of American municipal laws over the claimant’s person within the territorial jurisdiction of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Before an arbitral tribunal could be established by the PCA, it had to determine that the dispute was international, which meant the Hawaiian Kingdom had to be an existing State under customary international law. Once the PCA recognized the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State and the Council of Regency as its government, it then had to determine whether the Hawaiian Kingdom was a Contracting State or Non-Contracting State to the 1907 Hague Convention for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes (PCA Convention) that established the PCA.

The reasoning for this determination was that Contracting States, which includes the United States, did not pay for the use of the facilities because they contributed yearly dues to maintain the PCA. Non-Contracting States had to pay for the use of the facilities. The PCA recognized the Hawaiian Kingdom as a Non-Contracting State under Article 47 of the PCA Convention. The PCA established the arbitral tribunal on June 9, 2000. To understand this case you can go to pages 24-27 of the ebook Royal Commission of Inquiry: Investigating War Crimes and Human Rights Violations Committed in the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The PCA’s recognition of the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1999 satisfied Phase I. Since then, Phase II was initiated and continued when Dr. Sai entered the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in 2001 to acquire an M.A. degree and a Ph.D. degree in political science specializing in international relations and law. According to Dr. Sai:

The Council of Regency needed to institutionalize, and not politicize, the legal and political history of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under international law and its continued existence today. This would be done by academic research and publications that will normalize the fact of the American occupation. From this premise, we could move into compliance to the law of occupation where the occupation will eventually come to an end by a treaty of peace. This was the most viable approach to a revisionist history that has been perpetrated for over a century.

Awaiaulu—Video Story of Hawaiian Independence

Hawai‘i and the U.S. Army Doctrine of Command Responsibility for War Crimes

Normally when a crime is committed at the national level, a person not only has to commit the criminal act but also must have the criminal intent to commit the crime. In other words, for a person to be held criminally liable, he/she would also have known that the act was unlawful. Criminal culpability, under U.S. federal law, could also apply to a person who did not commit the crime themselves, but knew that a federal crime had been committed and did not report it. This is misprision of a felony that criminalizes the active concealment of a known felony without reporting it to the proper authorities. A felony is where the punishment of a crime is a year or more in prison. Less than a year in prison is a misdemeanor.

At the international level, a war crime can be committed by an individual as well as someone in authority who knew of the commission of the war crime and did nothing to prevent it or stop it. So, under international criminal law, there is the war crime committed by a perpetrator and there is the war crime by omission, which is the failure of a person in authority to act. The failure to act does not require criminal intent.

General Tomoyuki Yamashita was not only the most senior officer of the Japanese military in the Philippines, but he was also the military governor of the occupied territory of the Philippines. Under the law of occupation, the civilian population of the occupied State owe temporary obedience to the occupier, who in turn will protect their rights under the laws of the occupied State. The Philippines, at the time, were a part of the territory of the United States. So, when Japanese soldiers were killing American prisoners of war, they were also raping and killing civilians. It was argued that General Yamashita, as a person of authority, could have put a stop to these war crimes. He was found guilty and sentenced to death.

In 1945, General Yamashita was tried and convicted for the commission of war crimes, but he was not the perpetrator of the war crimes. In fact, he was not charged with war crimes. He was charged under the theory that he knew or should have known that war crimes were being committed against American prisoners of war and Filipino citizens and he did not put a stop to it or punish the perpetrators. This theory became a legal doctrine called command responsibility for war crimes.

Under this legal doctrine of command responsibility, there are the following three elements establishing criminal liability for war crimes by omission:

(1) there must be a superior-subordinate relationship;

(2) the superior must have known or had reason to know that the subordinate was about to commit a crime or had committed a crime; and

(3) the superior failed to take the necessary and reasonable measures to prevent the crime or to punish the perpetrator.

According to the U.S. Department of Defense draft instructions for guidance to military commissions states: “A person is criminally liable for a completed substantive offense if that person commits the offense, aids or abets the commission of the offense, solicits commission of the offense, or is otherwise responsible due to command responsibility,” and provides the following elements:

(1) The accused had command and control, or effective authority and control, over one or more subordinates;

(2) One or more of the accused’s subordinates committed, attempted to commit, conspired to commit, solicited to commit, or aided or abetted the commission of one or more substantive offenses triable by military commission;

(3) The accused either knew or should have known that the subordinate or subordinates were committing, attempting to commit, conspiring to commit, soliciting, or aiding and abetting such offense or offenses; and

(4) The accused failed to take all necessary and reasonable measures within his or her power to prevent or repress the commission of the offense or offenses.

These four elements are the same under customary international law. According to an authoritative study of customary international law by the International Committee of the Red Cross:

Commanders and other superiors are criminally responsible for war crimes committed by their subordinates if they knew, or had reason to know, that the subordinates were about to commit or were committing such crimes and did not take all necessary and reasonable measures in their power to prevent their commission, or if such crimes had been committed, to punish the persons responsible.

The U.S. Army updated Army Regulation 600-20, Army Command Policy, which states under the heading of Command responsibility under the law of war:

4-24. Commanders are legally responsible for war crimes they personally commit, order committed, or know or should have known about and take no action to prevent, stop, or punish.

Consequently, if commanders ‘know or should have known’ that war crimes are being committed and ‘take no action to prevent, stop, or punish,’ they could be held criminally liable for the war crime by omission.

It is uncontested by the United States, the State of Hawai‘i, and the Counties that war crimes, under customary international law, are occurring throughout the Hawaiian Islands. It is also uncontested that the Hawaiian Kingdom continues to exist as an occupied State and that the Council of Regency is its acting government. Legal opinions by Professor William Schabas, Professor Matthew Craven, and Professor Federico Lenzerini who are international law scholars, explain this under the rules of customary international law.

Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice identifies five sources of international law: (a) treaties between States; (b) customary international law derived from the practice of States; (c) general principles of law recognized by civilized nations; and, as subsidiary means for the determination of rules of international law; (d) judicial decisions; and (e) the writings of “the most highly qualified publicists.” These writings by these scholars are from “the most highly qualified publicists,” and are, therefore, a source of customary international law.

According to Professor Malcolm Shaw, “Because of the lack of supreme authorities and institutions in the international legal order, the responsibility is all the greater upon publicists of the various nations to inject an element of coherence and order into the subject as well as to question the direction and purposes of the rules.” Thus, Professor Shaw states, “academic writings are regarded as law-determining agencies, dealing with the verification of alleged rules.” This is consistent with how the U.S. Supreme Court views the writing of international scholars. In the Paquette Habana case, Supreme Court explained:

International law is part of our law, and must be ascertained and administered by the courts of justice of appropriate jurisdiction, as often as questions of right depending upon it are duly presented for their determination. For this purpose, where there is no treaty, and no controlling executive or legislative act or judicial decision, resort must be had to the customs and usages of civilized nations; and, as evidence of these, to the works of jurists and commentators, who by years of labor, research and experience, have made themselves peculiarly well acquainted with the subjects of which they treat. Such works are resorted to by judicial tribunals, not for the speculations of their authors concerning what the law ought to be, but for trustworthy evidence of what the law really is (emphasis added).

As a source of international law, the legal opinions establish a shift in the burden of proof. The presumption of State continuity shifts the burden of proof as to what is to be proven and by whom to rebut this presumption. Like the presumption of innocence, the accused does not prove their innocence, but rather the prosecution must prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that person’s guilt. Likewise, the Hawaiian Kingdom need not prove its continued existence, but rather, the United States must prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that it extinguished the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under international law.

Without such proof the State of Hawai‘i is illegitimate. It would stand to reason that the United States would have rebutted these legal opinions but it cannot because there are no rules of customary international law that can substantiate the lawfulness of the American presence in the Hawaiian Islands, to include the State of Hawai‘i. The only rules of international law that would temporarily allow the presence of the United States is through its military under the law of occupation and the duty to establish a military government. This is explained by the Permanent Court of International Justice in the Lotus case, which was a dispute between France and Turkey. The Court stated::

Now the first and foremost restriction imposed by international law upon a State is that—failing the existence of a permissive rule to the contrary—it may not exercise its power in any form in the territory of another State. In this sense jurisdiction is certainly territorial; it cannot be exercised by a State outside its territory except by virtue of a permissive rule derived from international custom or from a convention [treaty].

Since returning from the international arbitration proceedings in Larsen v. Hawaiian Kingdom in the Netherlands in December of 2000, where the Permanent Court of Arbitration recognized the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State under international law, the Council of Regency focused its attention on exposing the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an occupied State since January 17, 1893. The Regency also framed the exposure through international humanitarian law, the law of occupation, and the consequential war crimes that have and continue to be committed.

Under the law of occupation, the occupant of the occupying State, being the State of Hawai‘i, is obligated to protect the private rights of the Hawaiian citizenry. The occupant protects these rights by establishing a military government in order to administer the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. After unlawfully overthrowing the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893, the U.S. military did not follow this international rule.

Instead, the United States allowed their puppet, calling itself the provisional government, to unlawfully maintain control of the machinery of the Hawaiian Kingdom government. President Grover Cleveland told the Congress that the “provisional government owes its existence to an armed invasion by the United States.”

These insurgents changed their name, in 1894, to the so-called Republic of Hawai‘i. In 1898, at the height of the Spanish-American War, the United States merely enacted a federal law purporting to have annexed the Hawaiian Islands. This was all in violation of international law and the law of occupation. According to U.S. Army Field Manual 6-27 under the heading Limitations of Occupation:

6-24. Military occupation of enemy territory involves a complex, trilateral set of legal relations between the Occupying Power, the temporarily ousted sovereign authority, and the inhabitants of the occupied territory. Military occupation does not transfer sovereignty to the Occupying Power, but simply gives the Occupying Power the right to govern the enemy territory temporarily.

6-25. The fact of a military occupation does not authorize the Occupying Power to take certain actions. For example, the Occupying Power is not authorized by the fact of a military occupation to annex occupied territory or create a new State. Nor may the Occupying Power compel the inhabitants of occupied territory to become its nationals or otherwise swear allegiance to it.

Despite the United States own Army Field Manual that states, ‘the Occupying Power is not authorized by the fact of military occupation to annex occupied territory or create a new State,’ it is, in fact, what the United States did when it unilaterally annexed the Hawaiian Islands in 1898 and created the State of Hawai‘i and its Counties in 1959. While these acts are clearly violations of international humanitarian law and the law of occupation, it did not affect, nor did it alter the sovereignty of the Hawaiian Kingdom. These acts also did not change the legal status of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an occupied State, which the Permanent Court of Arbitration recognized on November 8, 1999, when international arbitration proceedings were initiated.

Instead, these unlawful acts set in motion for the commission of the war crime of usurpation of sovereignty during military occupation, which is the unlawful imposition of American laws and administrative measures of the occupying State over the territory of the occupied State. This war crime triggered secondary war crimes that include the war crime of compulsory enlistment; the war crime of denationalization; the war crime of confiscation or destruction of property; the war crime of deprivation of fair and regular trial; the war crime of deporting civilians of the occupied territory; and the war crime of transferring populations into an occupied territory.

Lieutenant Colonel Michael Rosner became the most senior officer in the Hawai‘i Army National Guard because of war crimes by omission committed by Major General Kenneth Hara-War Criminal Report no. 24-0001, Brigadier General Stephen Logan-War Criminal Report no. 24-0002, Colonel Wesley Kawakami-War Criminal Report no. 24-0003, Lieutenant Colonel Fredrick Werner-War Criminal Report no. 24-0004, Lieutenant Colonel Bingham Tuisamatatele, Jr.-War Criminal Report no. 24-0005, Lieutenant Colonel Joshua Jacobs-War Criminal Report no. 24-0006, and Lieutenant Colonel Dale Balsis-War Criminal Report no. 24-0007.

After they were made aware of war crimes being committed throughout the Hawaiian Islands, each of these Army commanders failed to put a stop to these war crimes. Although, each of these commanders did not commit the war of usurpation of sovereignty during military occupation themselves, they have criminal liability under the legal doctrine of command responsibility for war crimes because they did not establish a military government that would have brought these war crimes to an end. Under the law of occupation, as stated in U.S. Army Field Manual 27-5:

(1) Civil affairs/military government (CA/MG). CA/MG encompasses all powers exercised and responsibilities assumed by the military commander in an occupied or liberated area with respect to the lands, properties, and inhabitants thereof, whether such administration be in enemy, allied, or domestic territory. The type of occupation, whether CA or MG, is determined by the highest policy making authority. Normally, the type of occupation is dependent upon the degree of control exercised by the responsible military commander.

(2) Military government. The term “military government” as used in this manual is limited to and defined as the supreme authority exercised by an armed occupying force over the lands, properties, and inhabitants of an enemy, allied, or domestic territory. Military government is exercised when an armed force has occupied such territory, whether by force or agreement, and has substituted its authority for that of the sovereign or previous government. The right of control passes to the occupying force limited only by the rules of international law and established customs of war.

(3) Civil affairs. The term “civil affairs” as used in this manual is defined as the assumption by the responsible commander of an armed occupying force of a degree of authority less than the supreme authority assumed under military government, over enemy, allied, or domestic territory. The indigenous governments would be recognized by treaty, agreement, or otherwise as having certain authority independent of the military commander.

(4) Occupied territory. The term “occupied territory” as used in this manual means any area in which CA/MGis exercised by an armed occupying force. It does not include territory in which an armed force is located but has not assumed authority.

3. COMMAND RESPONSIBILITY. The theater commander bears full responsibility for CA/MG; therefore, he is usually designated as military governor or civil affairs administrator, but is authorized to delegate his authority and title, in whole or in part, to a subordinate commander. In occupied territory the commander, by virtue of his position, has supreme legislative, executive, and judicial authority, limited only by the laws and customs of war and by directives from higher authority.

4. REASON FOR ESTABLISHMENT. a. Reasons for the establishment of CA/MG are either military necessity as a right, or as an obligation under international law. b. Since the military occupation of enemy territory suspends the operation of the government of the occupied territory, the obligation arises under international law for the occupying force to exercise the functions of civil government looking toward restoration and maintenance of public order. These functions are exercised by CA/MG. An armed force in territory other than that of an enemy similarly has the duty of establishing CA/MG when the government of such territory is absent or unable to function properly.

LTC Rosner has found himself in a position not of his own making, but rather because of war crimes by omission committed by previous commanders under the Army doctrine of command responsibility for war crimes. As an Executive Officer for the 29th Infantry Brigade, he does not have the legal background to understand international law except what is in Army doctrine and regulations. He does, however, have a judge advocate (JAG) named Lieutenant Colonel Lloyd Phelps whose duty is to give legal advice to commanders, which LTC Rosner finds himself in.

As Major Michael Winn, a JAG, stated in his article 2022 article Command Responsibility for Subordinates’ War Crimes: A Twenty-First Century Primer that was published in vol. 2 of Army Lawyer, “In this era of increased focus on command responsibility for war crimes, legal advisors have an important role to play in helping their commanders prevent, stop, and punish such offenses. Accordingly, legal advisors keep their commanders on the high road of command responsibility.”

LTC Rosner has until November 28, 2024, to transform the State of Hawai‘i into a military government in accordance with U.S. Department of Defense Directive 5100.1, U.S. Army Field Manual 6-27—chapter 6, and the law of occupation. For LTC Rosner not to so, after being made aware of the commission of war crimes, he, like the commanders before him will be the subject of a war criminal report by the Royal Commission of Inquiry for the war crime by omission.

For LTC Rosner to not have criminal liability under the command responsibility for war crimes, LTC Phelps will need to show a legal basis, under customary international law, that the United States extinguished the Hawaiian Kingdom as a State. To do so, LTC Phelps will need to provide LTC Rosner an international treaty where the Hawaiian Kingdom ceded its sovereignty and territory to the United States. This he cannot do because there is no such treaty.