Hawaiian governance drew from political ideas of other countries as well as the experience of Hawaiian rulers. Hawai‘i’s history and circumstances were unique because Hawai‘i did not experience the peasant uprisings and revolutions that occurred in Great Britain and France. Legal cultures throughout Europe and the United States did, however, influence the leadership of the Hawaiian Kingdom, especially in the formative years of its transformation from absolute rule to constitutional governance.

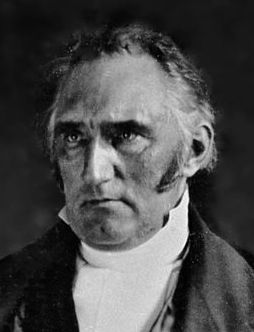

Early in his reign, Kamehameha III’s government stood upon the crumbling foundations of a feudal autocracy that could no longer handle the weight of geo-political and economic forces sweeping across the islands. Uniformity of law and the centralization of authority had become a necessity. Increased commercial trade brought an influx of foreigners wishing to reside and conduct business in the Kingdom, requiring changes in the legal system. In 1831, British General William Miller made the following observation of Hawaiian governance at the time:

If then the natives wish to retain the government of the islands in their own hands and become a nation, if they are anxious to avoid being dictated to by any foreign commanding officer that may be sent to this station, it seems to be absolutely necessary that they should establish some defined form of government, and a few fundamental laws that will afford security for property; and such commercial regulations as will serve for their own guidance as well as for that of foreigners; if these regulations be liberal, as they ought to be, commerce will flourish, and all classes of people will be gainers.

If then the natives wish to retain the government of the islands in their own hands and become a nation, if they are anxious to avoid being dictated to by any foreign commanding officer that may be sent to this station, it seems to be absolutely necessary that they should establish some defined form of government, and a few fundamental laws that will afford security for property; and such commercial regulations as will serve for their own guidance as well as for that of foreigners; if these regulations be liberal, as they ought to be, commerce will flourish, and all classes of people will be gainers.

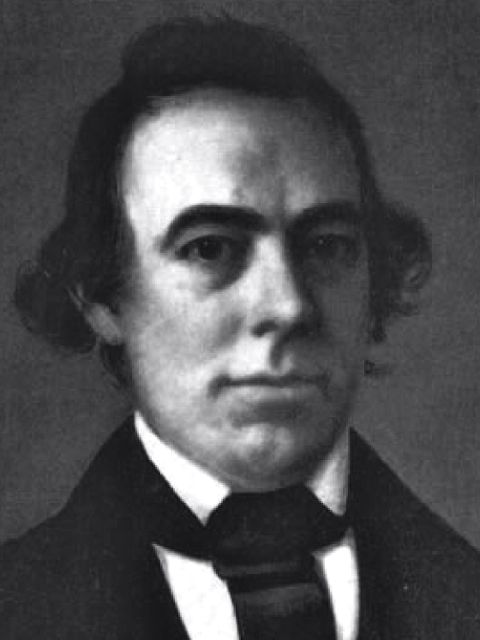

Kamehameha III turned to his religious advisors—the missionaries—for advice. William Richards volunteered to travel to the United States in search of someone to instruct the chiefs on government reform. When Richards was unable to find an instructor he dedicated himself, at the urging of Kamehameha III, to instruct the chiefs on political economy and governance. Richards had no formal education in political science or law but relied on the work of the President of Brown University, Francis Wayland. Wayland was interested in “defining the limits of government by developing a theory of contractual enactment of political society, which would be morally and logically binding and acceptable to all its members.”

Kamehameha III turned to his religious advisors—the missionaries—for advice. William Richards volunteered to travel to the United States in search of someone to instruct the chiefs on government reform. When Richards was unable to find an instructor he dedicated himself, at the urging of Kamehameha III, to instruct the chiefs on political economy and governance. Richards had no formal education in political science or law but relied on the work of the President of Brown University, Francis Wayland. Wayland was interested in “defining the limits of government by developing a theory of contractual enactment of political society, which would be morally and logically binding and acceptable to all its members.”

Richards developed a curriculum based upon Hawaiian translations of Wayland’s two books, “Elements of Moral Science (1835)” and “Elements of Political Economy (1837).” According to Richards, the “lectures themselves were mere outlines of general principles of political economy, which of course could not have been understood except by full illustration drawn from Hawaiian custom and Hawaiian circumstances.” Richards sought to  theorize governance from a foundation of natural rights within an agrarian society based upon capitalism that was not only cooperative in nature, but also morally grounded in Christian values. His translation of Wayland’s Elements of Political Economy, states “Peace and tranquility are not maintained when righteousness is not maintained. The righteousness of the chiefs and the people is the only basis for maintaining the laws of the government.” Laws should be enacted to maintain a society for the benefit of all and not the few.

theorize governance from a foundation of natural rights within an agrarian society based upon capitalism that was not only cooperative in nature, but also morally grounded in Christian values. His translation of Wayland’s Elements of Political Economy, states “Peace and tranquility are not maintained when righteousness is not maintained. The righteousness of the chiefs and the people is the only basis for maintaining the laws of the government.” Laws should be enacted to maintain a society for the benefit of all and not the few.

Richards asserted, “God did not establish man as servants for the chiefs and as a means for chiefs to become rich. God provided for the occupation of government leaders in order to bless the people and so that the nation benefits.” Wayland’s theory of cooperative capitalism, with private ownership of land and a free market as the foundation of political economy, was difficult to implement because the Kingdom was in a feudal state since the rule of Kamehameha I. Individuals could not hold land titles in the form of freehold titles, e.g. fee-simple and life estates. Therefore, personal property and agriculture formed the basis of the Hawaiian economy at this stage. According to an 1840 statute,

“The business of the Governors, and land agents [Konohiki], and tax officers of the general tax gatherer, is as follows: to read frequently this law to the people on all days of public work, and thus shall the landlords do in the presence of their tenants on their working days. Let every one also put his own land in a good state, with proper reference to the welfare of the body, according to the principles of Political Economy. The man who does not labor enjoys little happiness. He cannot obtain any great good unless he strives for it with earnestness. He cannot make himself comfortable, not even preserve his life unless he labor for it. If a man wish to become rich, he can do it in no way except to engage with energy in some business. Thus Kings obtain kingdoms by striving for them with energy.”

The Hawaiian Kingdom was moving towards developing and adhering to the “rule of law,” where there exists a government of law and not a government of chiefs. In the preamble of the 1840 Constitution it provides, “Protection is hereby secured to the persons of all the people, together with their lands, their building lots, and all their property, while they conform to the laws of the kingdom, and nothing whatever shall be taken from any individual except by express provision of the laws. Whatever chief shall act perseveringly in violation of this constitution, shall no longer remain a chief of the Hawaiian Islands, and the same shall be true of the Governors, officers, and all land agents.”

Under a feudal autocracy, the chiefs who held authority over the people under them had the sole authority to enact laws, execute laws and be the judge of the violation of these laws over the people. Hawaiian constitutionalism sought the transfer of the inherent authority of the chiefs into a single government that would enact laws that would apply equally to both chiefs and people together. To do this would be to achieve the cornerstone of constitutionalism—separation of powers.

Separation of powers refers to government responsibilities divided into distinct branches that prevent one branch from exercising the function of another branch. Hawaiian constitutional law separates government into three branches: the legislative, which is responsible for enacting laws and appropriating a budget for the operation of government; the executive, which is responsible for executing laws enacted by the legislative branch and the administration of government; and the judicial, which is responsible for the interpretation of the constitution and laws when disputes are brought before the courts.

Although, the Hawaiian Kingdom was a constitutional monarchy since 1840, it did not achieve the separation of powers until 1864. For 24 years the Hawaiian government operated more under a theory of sharing of power between the three Estates of the kingdom: the Monarch, Nobles and the People, rather than a separation of power theory. Under the first constitution in 1840, the King’s duty was to execute the laws of the land, serve as chief judge of the Supreme Court, and sit as a member of the House of Nobles that would enact laws together with representatives chosen from the People.

The 1852 Constitution was the first step toward separating the branches, where Article 23 stated: “The Supreme power of the Kingdom, in its exercise, is divided into the Executive, Legislative and Judicial; these are to be preserved distinct; the two last powers cannot be united in any one individual or body.” The King, however, who heads executive branch, could still create legislation without the participation of the legislative branch. Article 45 provided, “All important business of the Kingdom which the King chooses to transact in person, he may do, but not without the approbation of the Kuhina Nui (Premier). The King and the Kuhina Nui shall have a negative on each other’s public acts.” In other words, this provision was a loophole that needed to be addressed. Another cross over of branches under the 1852 Constitution were that two sitting Justices of the Hawaiian Kingdom Supreme Court, George M. Robertson and Lawrence McCully, were elected Representatives in the legislative branch. Both Justices also served as Speaker of the House of Representatives.

The separation of powers was finally accomplished under the 1864 Constitution when the provision of Article 45 was removed and Judges were barred from serving as elected Representatives in the Legislative Assembly. Article 20 of the 1864 Constitution provides, “The Supreme Power of the Kingdom in its exercise, is divided into the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial; these shall always be preserved distinct, and no Judge of a Court of Record shall ever be a member of the Legislative Assembly.”

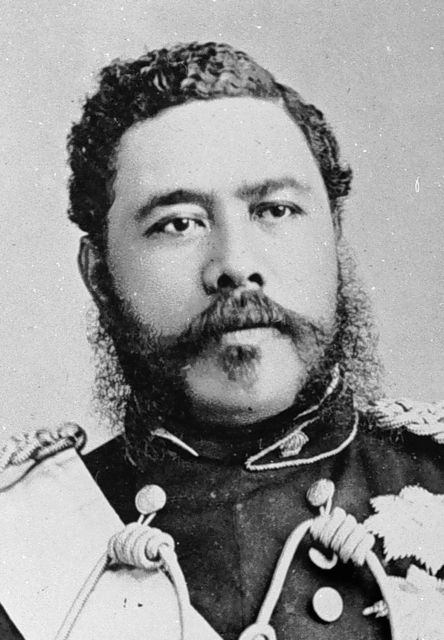

When King Kalakaua was forced to sign the 1887 Bayonet Constitution, he did so as the head of the executive branch, which was separate and distinct from the legislative branch. Since 1864, the executive was limited and confined to executing Hawaiian laws enacted by the Legislative Assembly and the administration of government. It did not have the ability to enact legislation as Kamehameha V did under Article 45 of the 1852 Constitution. The only branch that could change or amend the 1864 Constitution was solely the legislative branch. According to Article 80 of the 1864 Constitution:

When King Kalakaua was forced to sign the 1887 Bayonet Constitution, he did so as the head of the executive branch, which was separate and distinct from the legislative branch. Since 1864, the executive was limited and confined to executing Hawaiian laws enacted by the Legislative Assembly and the administration of government. It did not have the ability to enact legislation as Kamehameha V did under Article 45 of the 1852 Constitution. The only branch that could change or amend the 1864 Constitution was solely the legislative branch. According to Article 80 of the 1864 Constitution:

“Any amendment or amendments to this Constitution may be proposed in the Legislative Assembly, and if the same shall be agreed to by a majority of the members thereof, such proposed amendment or amendments shall be entered on its journal, with the yeas and nays taken thereon, and referred to the next Legislature; which proposed amendment or the next election of Representatives; and if in the next Legislature such proposed amendment or amendments shall be agreed to by two-thirds of all members of the Legislative Assembly, and be approved by the King, such amendment or amendments shall become part of the Constitution of this country.”

In his final report dated July 17, 1893, to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham, U.S. Special Commissioner, James Blount, interviewed the Chief Justice of the Hawaiian Kingdom that centered on the 1887 Bayonet Constitution. Unbeknownst to Blount at the time of the interview, the Chief Justice was a co-conspirator along with Associate Justice Edward Preston who assisted in the drafting of the Bayonet Constitution.

In his final report dated July 17, 1893, to U.S. Secretary of State Walter Gresham, U.S. Special Commissioner, James Blount, interviewed the Chief Justice of the Hawaiian Kingdom that centered on the 1887 Bayonet Constitution. Unbeknownst to Blount at the time of the interview, the Chief Justice was a co-conspirator along with Associate Justice Edward Preston who assisted in the drafting of the Bayonet Constitution.

Blount reported, “At this point I invite attention to the following extract from a formal colloquy between Chief Justice Judd and myself touching the means adopted to extort the constitution of 1887, and the fundamental changes wrought through that instrument:

Blount reported, “At this point I invite attention to the following extract from a formal colloquy between Chief Justice Judd and myself touching the means adopted to extort the constitution of 1887, and the fundamental changes wrought through that instrument:

Q. Was that constitution ever submitted to a popular vote for ratification?

A. No; it was not. There was no direct vote ratifying the constitution, but its provisions requiring that no one should vote unless he had taken an oath to support it, and a large number voted at that first election, was considered a virtual ratification of the constitution.

Q. If they voted at all they were considered as accepting it?

A. Yes, sir. I do not think any large number refused to take the oath to it.

Q. It was not contemplated by the mass meeting, nor the cabinet, nor anybody in power to submit the matter of ratification at all?

A. No, it was not. It was considered a revolution. It was a successful revolutionary act.

Q. And, therefore, was not submitted to a popular vote for ratification?

A. Yes, sir. It had mischievous effects in encouraging the Wilcox revolution of 1889, which was unsuccessful. I think it was a bad precedent, only the exigencies of the occasion seemed to demand it.

The 1887 Bayonet Constitution was never a constitution to begin with, but merely the act of an insurgency in the commission of the crime of high treason. The 1864 Constitution was never annulled and remained the Constitution of the country. To treat the 1887 Bayonet Constitution as if it were a Constitution of the country is to violate the Hawaiian Rule of Law, even if it was done through ignorance. But to move beyond ignorance is to dangerously move along the lines of the insurgency.

King Kalakaua and Queen Lili‘uokalani were not a part of any insurgency, but were Heads of State that had to deal with the insurgency that was both political and criminal. Both  Monarchs were not “above” the Constitution of the country, but were “under” it. This was acknowledged by the Queen in her diplomatic protest to the United States President on January 17, 1893. The protest stated, “I, Liliuokalani, by the grace of God and under the constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a provisional government of and for this Kingdom.”

Monarchs were not “above” the Constitution of the country, but were “under” it. This was acknowledged by the Queen in her diplomatic protest to the United States President on January 17, 1893. The protest stated, “I, Liliuokalani, by the grace of God and under the constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done against myself and the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a provisional government of and for this Kingdom.”

Everyone in the Hawaiian Islands is subject to the laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom, whether Hawaiian subjects or aliens. §6 of the Hawaiian Civil Code, provides:

“The laws are obligatory upon all persons, whether subjects of this kingdom, or citizens or subjects of any foreign State, while within the limits of this kingdom, except so far as exception is made by the laws of nations in respect to Ambassadors or others. The property of all such persons, while such property is within the territorial jurisdiction of this kingdom, is also subject to the laws.”

Excellent summary of the transition period. But I wonder if Kanaka Maoli get that capitalism and the rule of law are good things for them since for the most part we seem to loath such terms.

Well we loathe capalism because it has gotten us into the predicament today and its also one of the contributing factors to many of us being poor and homeless. The sad thing is that there really isnt much alternate options available to us.

Aloha Noa.

I have not read much loathing for capitalism or the rule of law, on this blog. I actually see a push for the compliance with the law more than loathing of it.

In my opinion, there is a place for capitalism in the Hawaiian Kingdom. It is a real part of our existence in a global community. I also believe that there are existing examples of how capitalism can be abused and the devestating effects it can have on society, when it is not regulated.

There is a video on this blog, I belive it was Umi Perkins, where there is mention of the arrival of capitalism here in the Hawaiian Kingdom, during the transformation into a constitutional monarchy. I am sure there is reference to our kupunas thoughts and ideas regarding capitalism.

In my research, I believe ancient Hawaiians were very far from being capitalistic. They appear to be more communal existing for the ali’i, or government. In exchange the ali’i / government would provide them what they required. There is one very appealing aspect to what this system achieved, a very high quality of life. You did not get to do whatever you liked, however life was not hard. There was a lot of time to holoholo, master your art or arts. The evidence of this is in our mo’olelo and artifacts. That all seems to come to an end when Europeans show up. There were a lot of new factors, including money, but I don’t know if it would be fair to say money was the problem. Definitely worth contemplation.

Realistically, we don’t live in the same world that our kupuna lived in. Can we apply those concepts in todays world and achieve the similar results? I believe that we can. However, if you are a capitalist, you won’t like my ideas. In my opinion, America is a shinning example of extreme capitalism and proves it does not work for the majority.

I believe there is a middle ground where capitalism is heavily regulated. Where the people of the Hawaiian Kingdom are working to maintain a strong stable government and economy. In return the government provides people with the things they require, lowering the cost of living and increasing the quality of life for everyone.

When you take an honest look of how are kupuna lived, survived and thrived, you will understand that their respect for their ‘aina, wai, kai and other resources is what enabled them to ho’oulu ka lahui. It is going to take years to undo the damage that has been done so far, but if we do not start taking care of our precious resources, we will be doomed!!