From the Editor of the Hawaiian Journal of Law and Politics, Professor Kalawai‘a Moore:

Since the attempted coup of 1887, history written on Hawaiʻi has been a highly political endeavor of a specific nature. The insurgents from the time of 1887 through the time of the United States coup de main of 1893 and beyond began writing a defensive justification narrative for their illegal actions as historical narratives. One among many of the distortions of historical truth has included a re-describing of the role of American missionary advisors in the earlier part of the 19th century as the driving force and main actors behind the development and running of a constitutional government of a nation-state. The motivations for the crafting of a history against which enormous primary evidence exists to the contrary was the aim at winning public and material support from the United States, and elsewhere to secure and maintain control over Hawaiʻi. Losing control over Hawaiʻi for the insurgents could have led to prosecution for treason under the law an offense that was punishable by death. Exemplifying this false narrative, Lorrin Thurston, one of these insurgents, wrote:

Hawaiian Christianization, civilization, commerce, education, and development are the direct product of American effort. Hawaii is in every element and quality which enters into the composition of a modern civilized community, a child of America.

As Hawaiians began to enter the battle of historical narratives in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, certain facts of history put forward in American hegemonic writings were latently taken up as foundational truths in the writings and teachings by Hawaiians themselves. One example of a false truth from the insurgents that was carried forward in Hawaiian written work was the false fact of the annexation of Hawaiʻi as a fait acompli. As a fact, the “annexation” of Hawaiʻi has been proven wrong in newer scholarship of the past 25 years. The so called annexation of Hawaiʻi is no longer an accepted fact by most Hawaiian scholars. Another example of a historical fallacy that still circulates today and still has several Hawaiian proponents, is the idea above that the early missionaries were the driving force behind the development and running of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s constitutional government. Professor Jon Osorio provides an example of a Hawaiian indigenist thesis based on this idea. He wrote:

Accordingly, the very formation of a national entity in 1840 under the rudiments of Euro-American constitutions victimized the Native Hawaiians, consigning them to unfamiliar and inferior roles as wage laborers. Caucasian newcomers proceeded to transform the economic and social systems, marginalizing the Native both demographically and symbolically.

Hawaiian indigenist writings about missionary primacy were a part of many theses that argued that the nation-state, law, and governance were western impositions and detrimental to ethnic Hawaiians in line with a thinking that these Hawaiians acquired through theoretical learning with other indigenous peoples. More recent Hawaiian written histories have unearthed primary source materials that show another vantage point that posits missionary involvement came in the middle of an already ongoing process of Hawaiian governmental and nation-state development.

The newer findings show that Hawaiʻi became a unified, centralized state under Kamehameha I with its own organized state structure, adopting features of British styled government long before missionary arrival. Under Kaʻahumanu’s rule, a set of Christian modelled laws were adopted through a dialectical process with missionary advisors, but the Prime Minister was clearly in charge. At the request of King Kamehameha III, Kauikeaouli, the government adopted a secular character. Former missionaries were taken in as advisors and played different roles in the development of Hawaiian governance and were eventually replaced during the reigns of King Kamehameha IV, Alexander Liholiho, and King Kamehameha V, Lota Kapuaiwa, by “Hawaiian chiefs and nonmissionary westerners.” The missionaries were taken on as advisors under Kaʻahumanu and Kauikeaouli, but were not the decision makers, and Hawaiian government was fashioned in a hybrid manner. The Hawaiian Kingdom government was aboriginal Hawaiian controlled and fashioned in a dialectical process based on traditional Hawaiian customs and relationships.

The first set of missionaries while trying to carry out their mission, served at the will of the chiefs. Their ability to stay on the islands was dependent on chiefly permission. The chiefs found the missionaries useful as teachers of new technologies and information. Some of these missionaries like William Richards, and Gerrit Judd left the mission and served the high chiefs full time as advisors on foreign relations and government. This first generation of missionaries spoke of themselves and were spoken of by others as loyal servants to the chiefs and the Hawaiian Kingdom. Sai notes this distinction between this first generation of missionaries and their descendants in his article “Synergy Through Convergence: The Hawaiian State and Congregationalism,” quoting the famous author Nordhoff, who was working as a correspondent for the newspaper Hawaii Holomua,

They, the fathers, stood by the natives against all foreign aggression. The elder Judd, a very able man, gave time, ability and his own means to the restoration of Hawaiian independence when it was attacked by an English admiral; his degenerate son, the present chief justice [Albert F. Judd] was part of the conspiracy which upset the government he had sworn to support and, himself a native of Hawaii, is active in the movement to destroy the State which his father gave a long life to establish defend and maintained.

This fifth volume of the Hawaiian Journal of Law and Politics contains a number of articles that engage further the agency and independence of aboriginal Hawaiian chiefly rulers, and their abilities to both stay ahead of any political intrigue, and to employ missionary knowledge of literacy and teaching to their advantage. We also see further the distinction that can be made between the first generation of missionaries and their loyalty to the Crown and government, versus some of their descendants, who formed an ideological position of white cultural supremacy, undertaking a treasonous course of action. This later generation showed a completely different attitude and approach to the Hawaiian Crown. Sai’s work further shows how aboriginal Hawaiian leadership from the Hawaiian Patriotic League clearly saw this distinction between the generations referring in testimony to many of the insurgent second and third generationers as the “faithless sons of missionaries and local politicians angered by continous political defeat.”

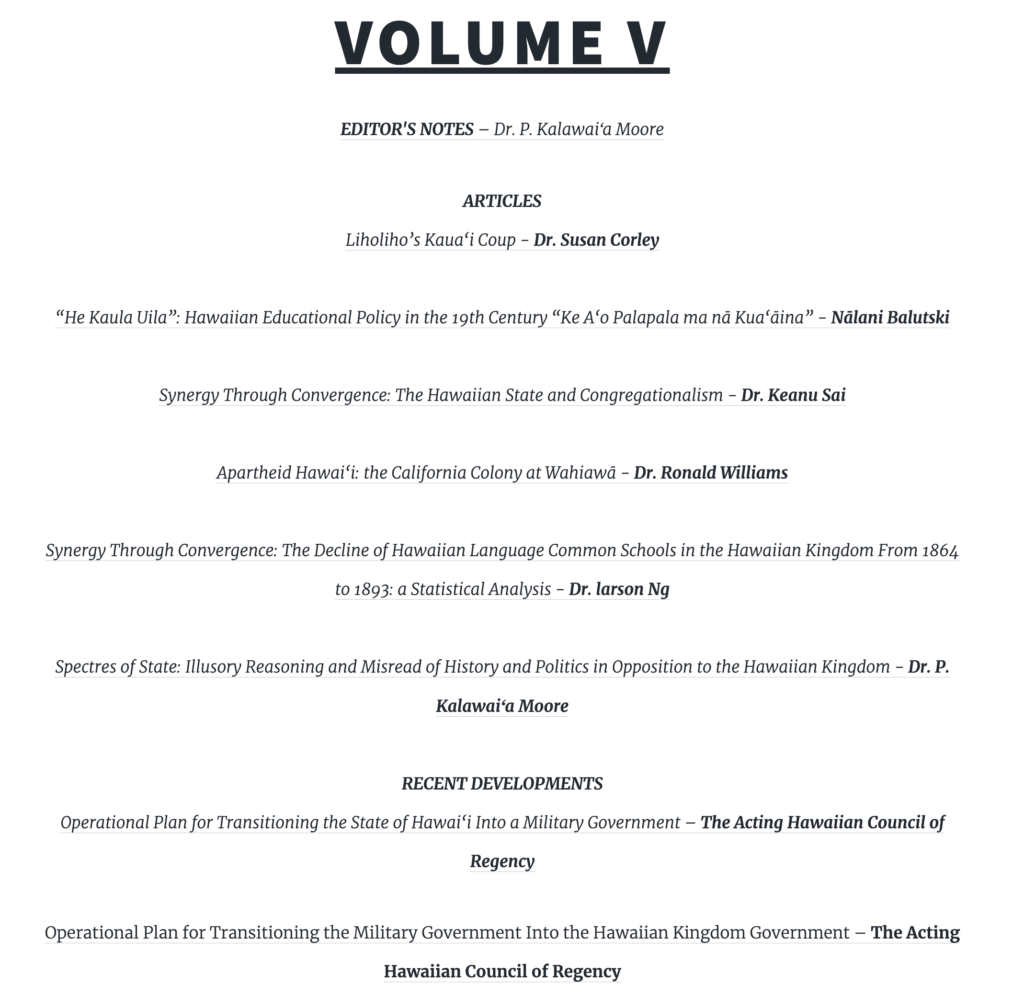

In the first article by Dr. Susan Corley “Liholiho’s Kauaʻi Coup,” we get an opportunity to understand better the character of King Kamehameha II, Liholiho, as ruler. Corley details an attempt by Hiram Bingham, a missionary of the first mission, to strengthen his position in the islands by enlisting the aid of Kaumualiʻi, King of the Island of Kaua‘i, suggesting the chief fund a mission to Tahiti. Liholiho intercedes using the occassion to outmaneuver both Bingham and Kaumualiʻi, taking full personal control of the island of Kauaʻi, and making it clear to the missionaries that he “held power and control over their ability to continue” their mission. Corley describes Liholihoʻs maneuvering and leadership as a matter of “guile where his father would have used force.”

In “‘He Kaula Uila’: Hawaiian Educational Policy in the 19th Century ‘Ke Aʻo Palapala ma Nā Aloaliʻi a me Nā Kuaʻāina,’” Brandi Jean Nalani Balutski starts with a more well-known excerpt from a speech made by Kauikeaouli upon ascension to the throne “he aupuni palapala koʻu” (mine is a kingdom of learning). Balutski details the chiefly adoption of the technology of literacy and education as formal policy of the early Hawaiian Kingdom and an ethos that education be taken up by all class levels. Balutski details the life journeys and roles of five aboriginal Hawaiian men who returned to Hawai‘i with these first missionaries acting as intermediaries between them and the ruling chiefs. Balutski shows how Thomas Hopu became the personal teachers for the high chiefs and their children. Others like George Humehume, son of Kaumuali‘i, became advisors for his father and their inner circle of chiefs who saw possible advantages in adopting literacy as a political tool. Despite initial concerns about the missionaries from the United States, their value in teaching literacy and the chiefs understanding of the value of literacy as a technology in dealing with various outsiders, paved the way for the acceptance of the American missionaries because of the benefit that literacy could hold “to control the encounter with foreigners, to favor their interests and those of their lineages, to express their understanding of the world, and to shape that world to their ends.”

In “Synergy Through Convergence: The Hawaiian State and Congregationalism,” Dr. Keanu Sai details further the distinction between the role of early American missionaries in support of the Hawaiian Kingdom government, and the later generations of “faithless sons of missionaries.” He starts by examining the rhetoric in history and political writings that has built a “myth of missionary control,” and contrasts these fabrications through use of the writings by aboriginal Hawaiians and supporters from the late 19th century, including a direct response by Kauikeaouli himself refuting a question of missionary control, and affirming his use of missionaries as teachers of literacy and translators between the government and foreign representatives. Sai shows a link between the congregationalism of the American missionaries and the influence of governmental reform in the Hawaiian Kingdom calling it a synergy whereby the “forces of both coalesced and each saw the other as beneficial to their own goals.” Sai illustrates the benefits to both sides during this time period to show further the false narratives that have been put forth stating that the “continuation of Americanism [was] initiated by the missionaries since 1820.”

In “Apartheid Hawai’i: California Colony at Wahiawā,” Dr. Ronald Williams Jr. continues his work showing the rise of white supremacist thought and action in Hawaiʻi starting with the break in local protestantism from congregationalism to a philosophy of “minority, White rule over both church and state” in the 1860s and 70s. Proponents of this change fomented an outright opposition to King Kalākaua during his reign, and supported the complete seizure of the government through U.S. facilitation in 1893, and then the full establishment of white oligarchic rule into the Territorial era in the 1900’s. Williams documents the efforts to establish a California Colony of white families in Wahiawā starting in 1899. This effort was made possible through earlier legislation called the 1895 Land Act introduced by Sanford Dole utilizing the newly confiscated Crown Lands for the express purpose of promoting “the immigration of permanent settlers of a character suitable for the building up of our population.” Williams documents the push by the government of the illegal Republic to settle white families on 1,350 acres of land before the “annexation” of the islands was completed. He further details the ideological drive behind the Dole government’s push to establish and support this community, which unashamedly sought to build a community of social and educational institutions based on the idea of racial segregation expressed as an “American way” as exemplified by the American South. The Wahiawā colony ultimately fails because of the greed of some of its backers and the success of pineapple farms like the one run by James Dole, which priced other small farmers out of the market.

In “The Decline of Hawaiian Language Common Schools During the Hawaiian Kingdom From 1864 to 1893: A Statistical Analysis,” Dr. Larson Ng walks through a quantitative data study of Hawaiian Kingdom government records on Hawaiian language common schools, English language schools, and independent schools looking at funding, attendance, and population statistics. Ng walks us through a brief history of the school system in the Hawaiian Kingdom and some of the theories in circulation that have tried to link causation of the decrease in aborginal attendence at Hawaiian language common schools to ideologies of “settler colonialism.” Ng’s regression analysis shows that the most important statistical factor in the decline of Hawaiian language common school attendance was the decline in the aboriginal Hawaiian population. He noted that funding disparities were a matter of aboriginal Hawaiian governmental prioritization, rather than an ideological imposition by outsiders.

In my article I provide an analysis of Dr. Kehaulani Kauanui’s book Paradoxes of Hawaiian Sovereignty: Land, Sex, and the Colonial Politics of State Nationalism, in which I call Kauanui’s work a remonstrance against Hawaiians turning toward the Hawaiian Kingdom, and a lament over the waning of Hawaiian indigeneity. I provide a critical analysis that Kauanui lacks any “deep evidentiary work on the matters” she covers, “leaving key source perspectives and facts out in some arguments.” I provide critical comment on her continued misuse and mentoring of the term “colonization” and her focus on the “state” instead of “government” as showing a lack of political and legal disciplinary awareness, and when taken with her attempt to reinvent the term “indigenous” for use in the Hawaiian context shows a kind of paradigm paralysis. I provide additional comment that Kauanui adds no insight of value in her examination of the Mahele in her book. She simply represents old, debunked theories and facts, adding only a new form of rhetorical approach which in my words, states that, “Almost every page in this chapter by Kauanui is inaccurate, and all of her imported theories irrelevant.” On matters of gender and sexuality, Kauanui starts from that earlier mentioned perspective that the missionaries controlled and were in charge of the lives, government, and state creation of the chiefs in Hawai’i, which I disprove. I agree that there were changes that were made in laws on marriage, coverture, and sex that need to be examined and cautioned against. I add that Kauanui is really engaged in a fight over the gender and sexual politics of today seeking to head off losses or maintain rights through closing off the Hawaiian Kingdom as political possibility. Toward building her case, I show that Kauanui left out key information and misarranged key source quotes that would otherwise show subversion, and ambivalence toward conservative laws on gender and coverture. Kauanui does not reveal that coverture was fought, slowly dismantled, and then repealed. And does not reveal that her own sources show women as “jural subjects” and in one case did not show how her source stated that they could not agree that women’s status diminished with government reform. I also caution against obscuring source material to argue politics, and I point out that, “It can be said that there were heteropatriarchal forces at work in the Hawaiian Kingdom, but one cannot say that the Hawaiian Kingdom is a heteropatriarchal government, [society], nor state.”

The last two sections of this volume of the Hawaiian Journal of Law and Politics include two documents recently published by the Council of Regency as the Occupied Government of the Hawaiian Kingdom. One entitled “Operational Plan for Transitioning the State of Hawai’i into a Military Government,” and the second, “Operational Plan for Transitioning the Military Government into the Hawaiian Kingdom Government.” Both documents were written by the acting Government, whose officers consist of Dr. David Keanu Sai, Kauʻi P. Sai-Dudoit, and Dexter Keʻeaumoku Kaʻiama, Esq.

In the “Operational Plan for Transitioning the State of Hawai’i into a Military Government,” the acting Government lays out in detail the historical and legal justifications for the actions needed to move from an illegal State of Hawaiʻi government to military government under international humanitarian law and the law of occupation.

A detailed history is provided from state recognition of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1843 through the U.S. invasion and overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government, to the U.S. military occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The Plan lays out “essential” and “implied” tasks including the setting up of a temporary administrator of the laws of the occupied state, the establishment of a military government, the proclamation of provisional laws, the disbanding of the State of Hawaiʻi Legislature and County Councils, setting up a temporary administrator of public buildings, real estate, forests, and agricultural estates that belong to the occupied state, and tasks that protect the institutions of the occupied state.

In the “Operational Plan for Transitioning the Military Government into the Hawaiian Kingdom Government,” the acting Government lays out plans for the withdrawal of U.S. armed forces, dealing with the Hawaiian state territory, reparations, and the seizing of property. The plan lays out details on the transition from a military government to the government of the Hawaiian Kingdom; the creation and ratification of a Treaty of Peace, the conducting of a national census, the convening of a Legisltive Assembly, who will then, based on the Hawaiian Kingdom constitution, begin to put together the rest of the Hawaiian Kingdom government. These two plans are the only plans of action for the restoration of the Hawaiian Kingdom government. The historical importance of including these documents as part of the Hawaiian Journal of Law and Politics can not be understated and it was the work of the Council of Regency that was able to get the Permanent Court of Arbitration to acknowledge the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent State that generated the impetus in the formation of the Hawaiian Society of Law and Politics at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and the establishment of the Hawaiian Journal of Law and Politics.

We close these Editor’s notes with a mahalo (gratitude) to the authors for their work examining topics of interest and importance, and we look forward to more academic work and discussion that persists toward that Kuleana of Scholarship we endeavor to uphold.

Will another powerful nation try to take over Hawaiians and will the people lose out on goverment financial assistance like ssi ,ssdi ,Medicare and other assistance

Another takeover is something that can be prevented by a peace treaty. As for social security or any other federal benefit or privilege, I’ll put it to you this way…freedom doesn’t require social security, and neither are you born with social security. You can have freedom or social security but you can’t have both!

I believe a supplement to Medicare will not be needed, since aboriginal Native Hawaiian’s will be covered under the Queen’s Hospital healthcare, subsidized by the HK Government.

Since most of us had already contributed some of our earnings into social security, wouldn’t we be paid back by reparation funds or a specific fund, then transition into a HK Government program, if any?

That makes sense. A reparations package could include the amounts of contributions (& taxes for that matter) into social security as part of the total reparations for the Hawaiian Kingdom.

My Guess: Re ppl losing out on govt assistance: Estimated reparations from USA to the Hawaiian Kingdom run from $2.3-trillion (shown in Council’s 2d Op Plan) to another est I’ve seen of $9.1-trillion. There will be sufficient funding to ensure no one is cut off from previously existing benefits & assistance that came from the USA Govt which would continue thru the transitional period to be later determined by a restored HK Legislature. / As far as being taken over… Any potential enemy, China/Russia, have not shown a modern history of just outright taking over a place or country without some sort of arguable legal claim per international law. (This was the case in Ukraine & South China Sea.) 1. There’s no conceivable “legal claim” against HI that either country could assert. 2. HI will be a Neutral nation. Any hostility toward it would earn such offender a forever-branded status as a pariah nation. Russia & China use international law as a cover, a mask, to support their propaganda purposes. It would be self-defeating for their long-range plans and propaganda poses to attack a neutral country (imagine the international outcry of Switzerland being attacked by some country today – same for future Neutral HK). 3. And, I think HI’s geo-strategic positioning in the middle of the Pacific is not what is commonly assumed for purposes of modern day war-fighting capabilities. Technological advances in warfare & its tools have made the long-held strategic location HI somewhat obsolete. Satellites, rocketry, cyber, naval & air vessels’ range, etc., have shrunken the globe and the allure of Pearl Harbor as being strategically significant has been greatly diminished, esp since the days of WWII, Vietnam & Cold War days. I suggest what we see in the existing militarization of Hawai’i as being, more or less, just a hang-over effect of former decades and now serves more as convenience than strategic positioning. In fact, as existing, with such a high concentration of military assets, Hawai’i is much more vulnerable than if those assets were spread around on the USA’s continent, Guam, Okinawa, S Korea, Japan, Australia, etc. / In this interview with Colonel Al Frenzel, US Army (Retired) – from eight yrs ago – he explains some of the myths of HI’s military importance. And, he gives insight as to how the “State of Hawai’i” could benefit from the military’s existing infrastructure & facilities. Keep in mind the context of the interview concerned a significant drawdown in the military, but the insight COL Frenzel brings forth can be used to extrapolate to the much larger picture of De-Occupation: https://youtu.be/QOnMeu8zMbY?si=cFSZ6PA27eNNfJDA

This is great…HSLP in the hale. A must read, get the popcorn!

This is a monumental moment. The de-occupation after 130 years is history in the making. I am surprised many different social sciences are not interested in researching and recording the process Hawaiian Kingdom is going through. Economists and both sociologist and psychologist should be sending out surveys. And surveying the people would help with figuring out what the nation has as far as skills and resources to work with and what will be needed. Also as the Hawaiian Kingdom gains power over it’s lands, will they be considering keeping certain businesses around because they are a hub of contracts for example, Safeway. Safeway has many contracts with venders who supply people with necessities. To help transition smoothly the commerce and economic side, I would imagine contracts will need to be maintained.

Also, will UH, being as aspect of the Hawaiian Kingdom, expand their education to all Hawaiian subjects like free classes on the internet.

This is an amazing moment where consideration in the economy can be defined to allow the people to thrive rather than survive. Where Cooperative Capitalism can lead the way to end inhumane practices of poverty.