From September 10-12, 2015, fifteen academic scholars from around the world who were political scientists and historians came together to present papers on non-European powers at a conference/workshop held at the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom. Attendees of the conference were by invitation only and the papers presented at the conference are planned to be published in a volume with Oxford University Press.

From September 10-12, 2015, fifteen academic scholars from around the world who were political scientists and historians came together to present papers on non-European powers at a conference/workshop held at the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom. Attendees of the conference were by invitation only and the papers presented at the conference are planned to be published in a volume with Oxford University Press.

The theme of the conference was Non-European Powers in the Age of Empire. These non-European countries included Hawai‘i, Iran, Turkey, China, Ethiopia, Japan, Korea, Thailand, and Madagascar. Dr. Keanu Sai was one of the invited academic scholars and his paper is titled “Hawaiian Neutrality: From the Crimean Conflict through the Spanish-American War.”

Many of these scholars were unaware of the history of the Hawaiian Kingdom and its “full” membership in the family of nations as a sovereign and independent state. What stood out for them was the continued existence of the Hawaiian Kingdom because it was only the government that was illegally overthrown by the United States and not the Hawaiian state, which is the international term for country. The belief that Hawai‘i lost its independence was dispelled and that its current status is a state under a prolonged American occupation since the Spanish-American War.

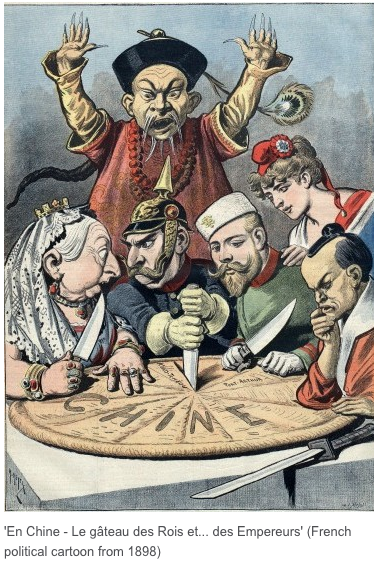

What was a surprise was that the Hawaiian Kingdom was the only non-European Power to have been a co-equal sovereign to European Powers throughout the 19th century. All other non-European Powers were not recognized as full sovereign states until the latter part of the 19th century and the turn of the 20th century. During this time European Powers imposed their laws within the territory of these countries under what has been termed “unequal treaties.”

Since 1858, Japan had been forced to recognize the extraterritoriality of American, British, French, Dutch and Russian law operating within Japanese territory. According to these treaties, citizens of these countries while in Japan could only be prosecuted under their country’s laws and by their country’s Consulates in Japan called “Consular Courts.” Under Article VI of the 1858 American-Japanese Treaty, it provided that “Americans committing offenses against Japanese shall be tried in American consular courts, and when guilty shall be punished according to American law.” The Hawaiian Kingdom’s 1871 treaty with Japan also had this provision, where it states under Article II that Hawaiian subjects in Japan shall enjoy “at all times the same privileges as may have been, or may hereafter be granted to the citizens or subjects of any other nation.” This was a sore point for Japanese authorities who felt Japan’s sovereignty should be fully recognized by these states.

While King Kalakaua was visiting Japan in 1881, Emperor Meiji “asked for Hawai‘i to grant full recognition to Japan and thereby create a precedent for the Western powers to follow.” Kalakaua was unable to grant the Emperor’s request, but it was done by his successor Queen Lili‘uokalani. Hawaiian recognition of Japan’s full sovereignty and repeal of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s consular jurisdiction in Japan provided in the Hawaiian-Japanese Treaty of 1871, would take place in 1893 by executive agreement through exchange of notes.

While King Kalakaua was visiting Japan in 1881, Emperor Meiji “asked for Hawai‘i to grant full recognition to Japan and thereby create a precedent for the Western powers to follow.” Kalakaua was unable to grant the Emperor’s request, but it was done by his successor Queen Lili‘uokalani. Hawaiian recognition of Japan’s full sovereignty and repeal of the Hawaiian Kingdom’s consular jurisdiction in Japan provided in the Hawaiian-Japanese Treaty of 1871, would take place in 1893 by executive agreement through exchange of notes.

By direction of Her Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani, R.W. Irwin, Hawaiian Minister to the Court of Japan in Tokyo sent a diplomatic note to Mutsu Munemitsu, Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs on January 18, 1893 announcing the Hawaiian Kingdom’s abandonment of consular jurisdiction. Irwin stated:

By direction of Her Majesty Queen Lili‘uokalani, R.W. Irwin, Hawaiian Minister to the Court of Japan in Tokyo sent a diplomatic note to Mutsu Munemitsu, Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs on January 18, 1893 announcing the Hawaiian Kingdom’s abandonment of consular jurisdiction. Irwin stated:

“Her Hawaiian Majesty’s Government reposing entire confidence in the laws of Japan and the administration of justice in the Empire, and desiring to testify anew their sentiments of cordial goodwill and friendship towards the Government of His Majesty the Emperor of Japan, have resolved to abandon the jurisdiction hitherto exercised by them in Japan.

It therefore becomes my agreeable duty to announce to your Excellency, in pursuance of instructions from Her Majesty’s Government, and I now have the honour formally to announce, that the Hawaiian Government do fully, completely, and finally abandon and relinquish the jurisdiction acquired by them in respect of Hawaiian subjects and property in Japan, under the Treaty of the 19th August, 1871.

There are at present from fifteen to twenty Hawaiian subjects residing in this Empire, and in addition about twenty-five subjects of Her Majesty visit Japan annually. Any information in my possession regarding these persons, or any of them, is at all times at your Excellency’s disposal.

While this action is taken spontaneously and without condition, as a measure demanded by the situation, I permit myself to express the confident hope entertained by Her Majesty’s Government that this step will remove the chief if not the only obstacle standing in the way of the free circulation of Her Majesty’s subjects throughout the Empire, for the purposes of business and pleasure in the same manner as is permitted to foreigners in other countries where Consular jurisdiction does not prevail. But in the accomplishment of this logical result of the extinction of Consular jurisdiction, whether by the conclusion of a new Treaty or otherwise, Her Majesty’s Government are most happy to consult the convenience and pleasure of His Imperial Majesty’s Government.”

On April 10, 1894, Foreign Minister Munemitsu, responded, “The sentiments of goodwill and friendship which inspired the act of abandonment are highly appreciated by the Imperial Government, but circumstances which it is now unnecessary to recapitulate have prevented an earlier acknowledgment of you Excellency’s note.”

This dispels the commonly held belief among historians that Great Britain was the first state to abandon its extraterritorial jurisdiction in Japan under the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation, which was signed on July 16, 1894. The action taken by the Hawaiian Kingdom did serve as “precedent for the Western powers to follow.”

Dr. Sai encourages everyone to read his paper “Hawaiian Neutrality: From the Crimean Conflict through the Spanish-American War” that was presented at Cambridge, which covers Hawai‘i’s political history from the celebrated King Kamehameha I to the current state of affairs today, and the remedy to ultimately bring the prolonged occupation to an end.

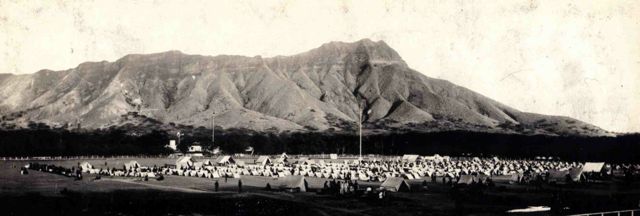

“The United States forces being now on the scene and favorably stationed, the committee proceeded to carry out their original scheme. They met the next morning, Tuesday, the 17th, perfected the plan of temporary government, and fixed upon its principal officers, ten of whom were drawn from the thirteen members of the Committee of Safety. Between one and two o’clock, by squads and by different routes to avoid notice, and having first taken the precaution of ascertaining whether there was any one there to oppose them, they proceeded to the Government building almost entirely without auditors. It is said that before the reading was finished quite a concourse of persons, variously estimated at from 50 to 100, some armed and some unarmed, gathered about the committee to give them aid and confidence. This statement is not important, since the one controlling factor in the whole affair was unquestionably the United States marines, who, drawn up under arms and with artillery in readiness only seventy-six yards distant, dominated the situation.”

“The United States forces being now on the scene and favorably stationed, the committee proceeded to carry out their original scheme. They met the next morning, Tuesday, the 17th, perfected the plan of temporary government, and fixed upon its principal officers, ten of whom were drawn from the thirteen members of the Committee of Safety. Between one and two o’clock, by squads and by different routes to avoid notice, and having first taken the precaution of ascertaining whether there was any one there to oppose them, they proceeded to the Government building almost entirely without auditors. It is said that before the reading was finished quite a concourse of persons, variously estimated at from 50 to 100, some armed and some unarmed, gathered about the committee to give them aid and confidence. This statement is not important, since the one controlling factor in the whole affair was unquestionably the United States marines, who, drawn up under arms and with artillery in readiness only seventy-six yards distant, dominated the situation.”

“In the heyday of empire, most of the world was ruled, directly or indirectly, by the European powers. On the eve of the First World War, only a few non-European states had maintained their formal sovereignty: Abyssinia (Ethiopia), China, Japan, the Ottoman Empire, Persia (Iran), and Siam (Thailand). Some others kept their independence for a while, but then succumbed to imperial powers, such as Hawaii, Korea, Madagascar, and Morocco. Facing imperialist incursion, the political elites of these countries sought to overcome their political vulnerability by engaging with the European powers and seeking recognition as equals.

“In the heyday of empire, most of the world was ruled, directly or indirectly, by the European powers. On the eve of the First World War, only a few non-European states had maintained their formal sovereignty: Abyssinia (Ethiopia), China, Japan, the Ottoman Empire, Persia (Iran), and Siam (Thailand). Some others kept their independence for a while, but then succumbed to imperial powers, such as Hawaii, Korea, Madagascar, and Morocco. Facing imperialist incursion, the political elites of these countries sought to overcome their political vulnerability by engaging with the European powers and seeking recognition as equals. Dr. David Keanu Sai was 1 of 15 scholars from across the world that was invited to present their research and expertise that centers on non-European States. Dr. Sai’s research focuses on the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign state and its continuity to date under an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States of America since the Spanish-American War. He will be presenting a paper titled “Hawaiian Neutrality: From the Crimean Conflict to the Spanish-American War.” The following is Dr. Sai’s abstract for his paper:

Dr. David Keanu Sai was 1 of 15 scholars from across the world that was invited to present their research and expertise that centers on non-European States. Dr. Sai’s research focuses on the Hawaiian Kingdom as an independent and sovereign state and its continuity to date under an illegal and prolonged occupation by the United States of America since the Spanish-American War. He will be presenting a paper titled “Hawaiian Neutrality: From the Crimean Conflict to the Spanish-American War.” The following is Dr. Sai’s abstract for his paper: